Some Washington School Districts Are Depending On Federal Relief Money To Pay For Reopening

BY HANNAH KRIEG / CROSSCUT

Before the school year started, Kirsten Koombs worked in the Moses Lake School District’s administrative office. She had some experience as a paraeducator and three months of an accelerated master’s in teaching under her belt.

Koombs is not a licensed teacher, but since Sept. 4, she has been teaching second grade remotely as one of the many emergency hires in the Moses Lake School District, paid for in part by the first federal Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief, or ESSER, Fund, which was passed by Congress in the March 2020 Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act.

Without emergency hires, the Moses Lake School District would not have the staffing necessary to comply with the Washington State Department of Health’s reopening guidelines, according to district Superintendent Dr. Joshua Meek. They are essential to the district’s reopening, he said.

On Feb. 19, Gov. Jay Inslee signed House Bill 1368, which appropriated $2.2 billion of COVID relief funding from the federal government. These funds were distributed among a variety of pandemic-induced needs. The big ticket item: $714 million of $13.2 billion allocated nationwide to assist K-12 education.

To receive money from this second ESSER Fund, school districts were required to submit reopening plans to the state by March 1. Superintendent of Public Instruction Chris Reykdal said last week that all but 35 school districts filed adequate reopening plans by the deadline. One of the districts that has yet to meet the requirement becaase their reopening plan didn’t meet all the state requirements is Seattle Public Schools. To receive the money, a school district must have plans to bring its students back to in-person learning.

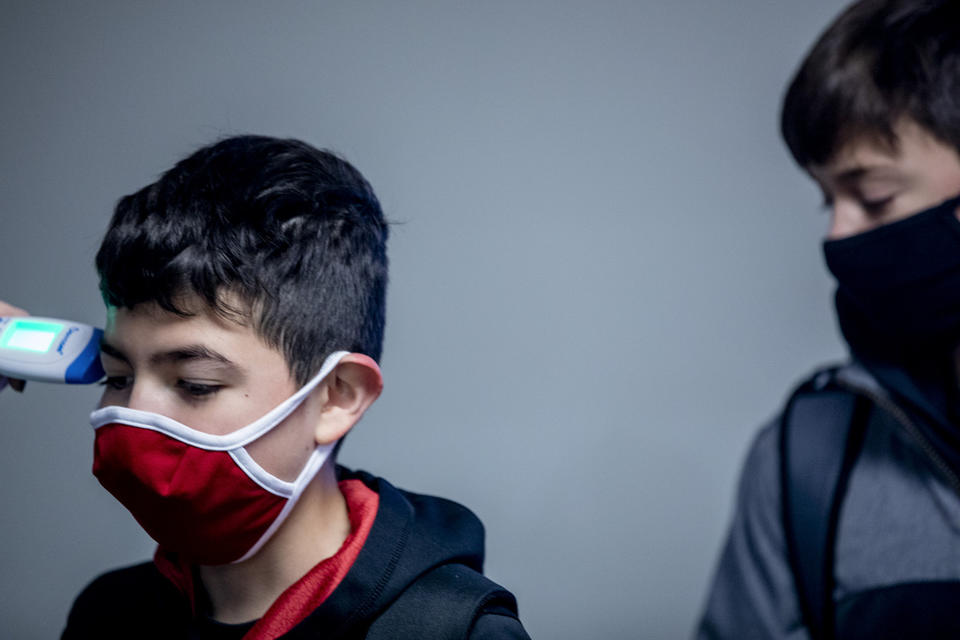

Moses Lake seventh grader Gabriel Barreto has his temperature taken during the health check-in before school starts at Chief Moses Middle School on Jan. 11, 2020. CREDIT: Dorothy Edwards/Crosscut

Seattle Public Schools stands to receive more funding than any other district in the state in the amount of $40.1 million, but it does not yet have the incoming funds “earmarked.”

“We don’t even know yet,” said district spokesperson Tim Robinson of how the second ESSER will be used. “This is all up in the air.”

According to Katy Payne, spokesperson for the OSPI, these funds are distributed on a reimbursement model, so time will tell eactly how these funds are being used. The first, smaller ESSER may be a good indication of how district’s will spend the latest COVID relief.

As of a February 2021 OSPI dashboard, 69.3% of the state’s first ESSER Fund has been claimed, with 288 of 310 eligible school districts claiming at least a portion of their allotted funding.

The Moses Lake School District has had a portion of its student body in desks since September 2020. Meek, the superintendent, said much of the first round of ESSER funds went to reopening efforts — where Seattle Public Schools sees itself now. How Moses Lake School District spent its first ESSER may guide other districts through the complicated process of reopening.

Reopening expenses

The biggest expense for reopening at the Moses Lake district was staffing. According to the Edunomics Lab at Georgetown University, opening schools to in-person learning has been a financial strain for school districts, which can be partially mitigated by federal relief dollars. Districts across the nation are finding budgets stretched by additional needs to hire more substitute teachers, pay for nursing staff, increase sanitizing efforts, pay for tutors, extend the school year and offer a bigger summer school program.

The Washington State Department of Health requires schools to employ cohorting — dividing the students into groups — and physical distancing for in-person classes. The result is smaller groups of students occupying more physical space and potentially requiring more teachers.

“[Health guidelines] require a much lower student-to-staff ratio,” Meek said. “To accomplish that, it’s a much more expensive staffing model.”

Meek said achieving this lower ratio has required some creativity. That’s where the emergency hires came in.

Holly Thompson has been a librarian at Garden Heights Elementary School in Moses Lake since 2014. Thompson does not have a teaching certificate, but raising five children of her own seemed like a decent qualification to her.

When Meek called in August to offer her a job teaching first grade remotely, Thompson was at Costco. She said she had to brace herself in the middle of the store. From that phone call, Thompson had three weeks to go from librarian to classroom teacher.

Although her duties changed, Thompson has not strayed too far from what she affectionately refers to as her “home away from home.” Thompson teaches out of what she estimates to be a 7-by-7-foot office off the Garden Heights Library. She is hoping to upgrade to her own classroom one day, as she now plans to go back to school to get her teaching certificate.

Paraeducators Jerilie Biery, left, and Nadia Ulyanchuk, right, administer required health check-ins with students before school starts at Chief Moses Middle School in Moses Lake on Jan. 11, 2020. CREDIT: Dorothy Edwards/Crosscut

“It’s funny, I was looking for a sign,” Thompson said. “My daughter says there’s been lots of signs, but this has been a big smack: ‘Go back to school.’ ”

Thompson said she has plenty of support from more experienced teachers. Although lesson plans were provided, audience retention of 6-year-olds on Zoom is a new challenge, even for a seasoned educator.

Thompson tries to keep the required material interesting. On what she called “Fun Friday,” Thompson taught a science lesson exploring the age-old question: Why are baby animals so cute? Students brought their own animals onto the call. Dogs, cats, a ferret, a bearded dragon and plenty of stuffed animals made an appearance that afternoon.

Koombs, who works out of an office at Midway Elementary in the district, said she acts out vocabulary words in her Zoom classes to keep students engaged.

“I must look ridiculous to anyone walking by my office,” Koombs said. “But it’s what helps my kids learn. It’s really helpful to be animated and over the top. I have a lot of kids who come just to see what I’m going to do next.”

According to Meek, the Moses Lake School District was ahead of the pack for remote learning because it is a one-to-one district, which means it already has a device for each student.

Computer connections

Spokane Public School is also a one-to-one school district, but its devices are stored in “computers on wheels” units equipped with built-in chargers. The district used much of its first $9.1 million ESSER Fund to buy new individual chargers and purchase online curriculum, said Andra Atwood, director of accounting at Spokane Public Schools.

According to a slideshow at its February school board meeting, the Yakima School District spent $4.7 million on student laptops, hotspots and online curriculum to adjust to online learning. Some of that spending was offset by its first $5.8 million ESSER Fund.

Seattle Public Schools reported using its first $10.7 million ESSER Fund grant to ensure all students had devices and internet access.

Despite best efforts to include and engage students in online learning, statewide enrollment for February is down by more than 40,000 students since last year, according to the OSPI. Younger students seemed to stay away from online learning the most, with a 14.7% drop in kindergarten enrollment statewide.

Thompson saw her own remote classroom go from 42 to 31 students in the first half of the year.

Because state funding is proportionate to the number of students, fewer students means less money. Payne, the spokesperson for the OSPI, said school districts will not see this loss in funding until the 2021-2022 school year.

Robinson, the spokesperson for Seattle Public Schools, said the district’s use of ESSER Funds will depend on state funding still being negotiated by the Legislature.

“There’s somewhat of an interplay between ESSER Funds and state funding,” Robinson said. “The clarity will come when the Legislature decides what to do.”

Spokane Public Schools’ Atwood said the district will continue to invest in personal protective equipment, sanitizer and signage as it phases students back into classrooms.

“We’ll continue to do exactly what we’re doing right now,” she said. “As needs arise and as funding comes in, we’ll make adjustments as we need to use it to the maximum capacity.”

The Moses Lake School District plans to use its second, $6.3 million ESSER Fund to address what Meek called “the aftermath of COVID-19.”

Under President Joe Biden’s directive, educators are now eligible for the vaccine. On March 2, Inslee moved educators and licensed child care workers to Washington’s Phase 1B-1, setting a clearer path for schools to reopen.

Meek has already received both doses of the vaccine.

“With a lot of uncertainty, our strategy for this second round is to sustain and look forward to next year,” Meek said.

Federal support will continue with the recently signed American Rescue Plan, which gives states a third ESSER Fund. Washington state will receive $1.85 billion in ESSER funding, 20% of which must address learning loss, according to the chief financial officer at OSPI, T.J. Kelly.

Correction: Fixes date of school reopening in the Moses Lake School District to September 2020.

Visit crosscut.com/donate to support nonprofit, freely distributed, local journalism.