BOOK REVIEW: ‘Outlawed’ Frontiers Of Gender And Sexuality Beckon In This Sly Western

Talking to friends this past week, I’ve described Anna North’s new novel, Outlawed, as The Handmaid’s Tale meets Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. That’s a glib tagline, but there’s some justification for it.

Outlawed opens in an alternative America of 1894 that was torn asunder by a flu epidemic some 60 years earlier. West of the Mississippi, centralized government has been replaced by a patchwork of Independent Towns. One of the few things this fragmented America agrees on is that women are put on Earth to bear children. That’s it. And, because too much knowledge, especially medical knowledge of women’s bodies, is frowned upon, “barren” women are regarded as freaks of nature, witches; they’re ostracized, imprisoned and sometimes put to death.

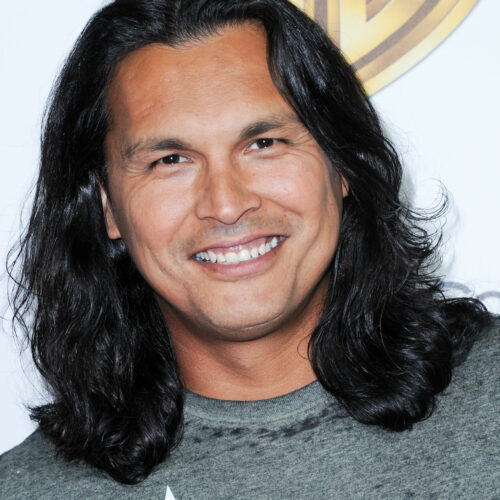

That status quo is pretty much OK with the heroine of Outlawed, a 17-year-old woman named Ada. She’s content to be married off to a man chosen for her and settles in to await her first pregnancy — which fails to happen. In less than a year, Ada is expelled from her husband’s house and, after a few twists of fate, joins up with the infamous Hole in the Wall Gang.

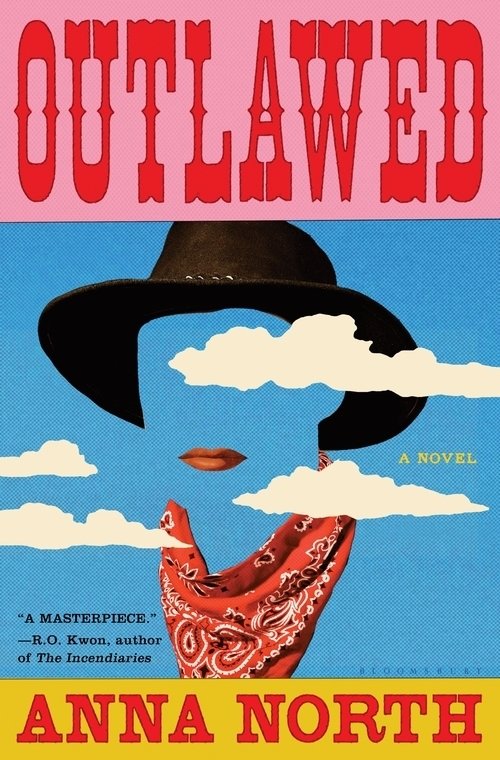

Outlawed by Anna North

In North’s novel, that real-life band of 19th-century gunslingers is reimagined as a group of outlaws who identify as female or non-binary. They’re led by a messianic figure called “The Kid.” In finding a home with the gang, Ada comes to realize that sexual desire can roam as wide and free as deer and buffalo on the range.

Outlawed, in this quick summary, can sound gimmicky, but there’s much more going on in this smart adventure tale than just a sly upending of the traditional Western, rooted in macho individualism and violence. For all the ways North ingeniously stretches the limits of the genre, she’s also clearly a fan. She doesn’t shy away from the expected gunfights and her rendering of such scenes is jittery and absorbing; but, North also dwells on the bloody aftermath of these shootouts and the damage that bullets do to the body.

In common with writers of classic Westerns, North also evokes the rugged landscape of the West, especially the area around the gang’s hideout with its salt flats, prairie dog burrows, and notched “wall of bright red rock many stories high” that gives The Hole in the Wall Gang its name. It’s there that the final showdown between the gang and the posse of lawmen who are pursuing them will take place.

Most of all, though, it’s the affecting character of Ada who’s the steady draw here. Once Fate tosses her out of her complacent life, Ada, in the time-honored tradition of the Western, becomes a hunter. Like Mattie Ross in True Grit or, dare I say Ethan Edwards, in the vexed John Ford film, The Searchers, Ada is on the trail, not of someone, but of something. She wants medical knowledge of women’s bodies.

Ada joins the gang for protection, but also to get loot from the hold-ups to be able to travel and study with a master midwife she’s heard about, a woman who practices farther west. Ada aims to save other infertile women from being ostracized or murdered. There’s a moment, after she settles in with the gang, when Ada almost decides to stay put. She tells us:

I saw how the valley, now blooming into beauty after the long winter, could feel like home. What I had planned instead was so amorphous and uncertain. …

But if I stayed in the valley, I would learn no more about myself or people like me than I had known when I left … I would die without knowing what made me the way I was.

The heroes of the traditional Western were always sure about what made them the way they were; what made a man a man. For Ada and the other “outlaws” of this spirited novel, the frontiers of gender and sexuality beckon to be explored.

9(MDAyOTk4OTc0MDEyNzcxNDIzMTZjM2E3Zg004))