Ground (And Sound)-Breaking Pilot Chuck Yeager Dies At 97; Had ‘The Right Stuff’ And Then Some

BY RUSSELL LEWIS

One of the world’s most famous aviators has died: Chuck Yeager — best known as the first to break the sound barrier — died at the age of 97.

A message posted to his Twitter account says, “Fr @VictoriaYeage11 It is w/ profound sorrow, I must tell you that my life love General Chuck Yeager passed just before 9pm ET. An incredible life well lived, America’s greatest Pilot, & a legacy of strength, adventure, & patriotism will be remembered forever.”

Yeager started from humble beginnings in Myra, W.Va., and many people didn’t really learn about him until decades after he broke the sound barrier — all because of a book and popular 1983 movie called The Right Stuff.

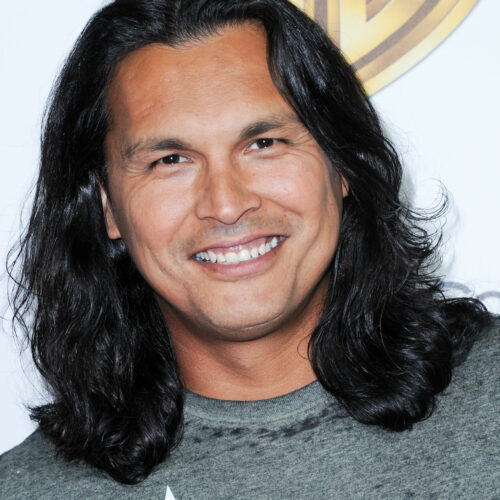

Yeager strikes a pose with Sam Shepard, who played him in the movie version of The Right Stuff. CREDIT: Warner Bros./Getty Images

He accomplished the feat in a Bell X-1, a wild, high-flying rocket-propelled orange airplane that he nicknamed “Glamorous Glennis,” after his first wife who died in 1990. It was a dangerous quest — one that had killed other pilots in other planes. And the X-1 buffeted like a bucking horse as it approached the speed of sound — Mach 1 — about 700 miles per hour at altitude.

But Yeager was more than a pilot: In several test flights before breaking the sound barrier, he studied his machine, analyzing the way it handled as it went faster and faster. He even lobbied to change one of the plane’s control surfaces so that it could safely exceed Mach 1.

As popularized in The Right Stuff, Yeager broke the sound barrier on October 14, 1947 at Edwards Air Force Base in California. But there were no news broadcasts that day, no newspaper headlines. The aviation feat was kept secret for months. In 2011, Yeager told NPR it never much mattered to him. “I was at the right place at the right time. And duty enters into it. It’s not, you know, you don’t do it for the — to get your damn picture on the front page of the newspaper. You do it because it’s duty. It’s your job.”

Yeager never sought the spotlight, and was always a bit gruff. After his famous flight in the X-1, he continued testing newer, faster and more dangerous aircraft. The X-1A came along six years later and it flew at twice the speed of sound. On December 12, 1953, Chuck Yeager set two more altitude and speed records in the X-1A: 74,700 feet and Mach 2.44.

It’s what happened moments later that cemented his legacy as a top test pilot. The X-1A began spinning viciously and spiraling to earth, dropping 50,000 feet in about a minute. His flight helmet even cracked the canopy, and a scratchy archive recording from the day preserves Yeager’s voice as he wrestles back control of the aircraft: “Oh! Huh! I’m down to 25,000,” he says calmly — if a little breathlessly. “Over Tehachapi. I don’t know if I can get back to base or not.”

Yeager would get back to base. And in this 1985 NPR interview, he said it was really no big deal: “Well, sure, because I’d spun airplanes all my life and that’s exactly what I did. I recovered the X-1A from inverted spin into a normal spin, popped it out of that and came on back and landed. That’s what you’re taught to do.”

It’s more than that, though. Yeager was a rare aviator, someone who understood planes in ways that other pilots just don’t. He ended up flying more than 360 different types of aircraft, and retired from the Air Force as a brigadier general. Bob van der Linden of the National Air and Space Museum in Washington says Yeager stood out. “He could give extremely detailed reports that the engineers found extremely useful. It’s not just flying the airplane, it’s interpreting how the airplane is flying and understanding that. And he understood that, just because he understood machines so well. And was just such a superb pilot.”

Chuck Yeager, standing next to the “Glamorous Glennis,” the Bell X-1 experimental plane in which he first broke the sound barrier.

CREDIT: AP

Yeager grew up in the mountains of West Virginia, an average student who never attended college. After high school, he enlisted in the Army Air Corps where he didn’t have the education credentials for flight training. But once the U.S. entered World War II a few months later, he got his chance.

Van der Linden says Yeager became a fighter ace, shooting down five enemy aircraft in a single mission and four others on a different day. Then he faced another challenge during a dogfight over France. “He got himself shot down and he escaped,” van der Linden says. “And very few people do that, and he managed not only to escape. He got back to England and normally they would ship people home after that. And he persuaded the authorities to let him fly again and he did which was highly unusual.” In addition to his flying skills, Yeager also had “better than perfect” vision: 20-10. He reportedly could see enemy fighters from 50 miles away and end up fighting in four wars.

Today, the plane Yeager first broke the sound barrier in, the X-1, hangs inside the Air and Space museum. Museum-goer Norm Healey was visiting from Canada and reading about Yeager’s accomplishments. “I loved airplanes as a kid. And Chuck Yeager was always sort of the cowboy of the airplane world. At least that was my perspective when I was young. As I’ve grown older and now have kids and a family and a wife, I appreciate it much more now, his courage.”

Yeager never considered himself to be courageous or a hero. He said he was just doing his job. A job that required more than skill. “All through my career, I credit luck a lot with survival because of the kind of work we were doing.”

Chuck Yeager spent the last years of his life doing what he truly loved: flying airplanes, speaking to aviation groups and fishing for golden trout in California’s Sierra Nevada mountains.

“Gen. Yeager’s pioneering and innovative spirit advanced America’s abilities in the sky and set our nation’s dreams soaring into the jet age and the space age,” NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine said in a statement late Monday. “Chuck’s bravery and accomplishments are a testament to the enduring strength that made him a true American original, and NASA’s Aeronautics work owes much to his brilliant contributions to aerospace science.”