‘Oak Flat’ Tells The Story Of An Apache Tribe Fighting To Save Its Land From Mining

BY LILY MEYER

Artist and writer Lauren Redniss creates books like no one else’s.

She mixes art, design, and rigorous research with a prose style that is at once assertive, journalistic and poetic. The results, though strictly based in fact, seem at once like graphic novels minus the familiar panel format, longform essays enriched by full-page drawings, and plays driven by monologue. Her sui generis style has earned her a MacArthur “genius” grant, a Guggenheim fellowship, and a National Book Award nomination for 2010’s Radioactive: Marie & Pierre Curie, which the award citation praised for “expand[ing] the realm of non-fiction.”

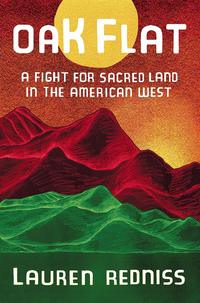

Redniss’ Oak Flat: A Fight for Sacred Land in the American West certainly feels expansive. It combines scientific and cultural history with contemporary testimony to tell the story of Oak Flat, a contested part of Arizona’s Tonto National Forest on which Resolution Copper — a subsidiary of the massive mining companies BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto — is agitating to open a colossal copper mine. To the San Carlos Apache Tribe, who have lived for generations on a reservation in southeastern Arizona, Oak Flat is sacred; Redniss quotes tribal chair Terry Rambler explaining to a Congressional committee, “‘Just as Mount Sinai is a holy place to Christians, Oak Flat is the equivalent to us.'”

Oak Flat: A Fight for Sacred Land in the American West, by Lauren Redniss

CREDIT: Random House

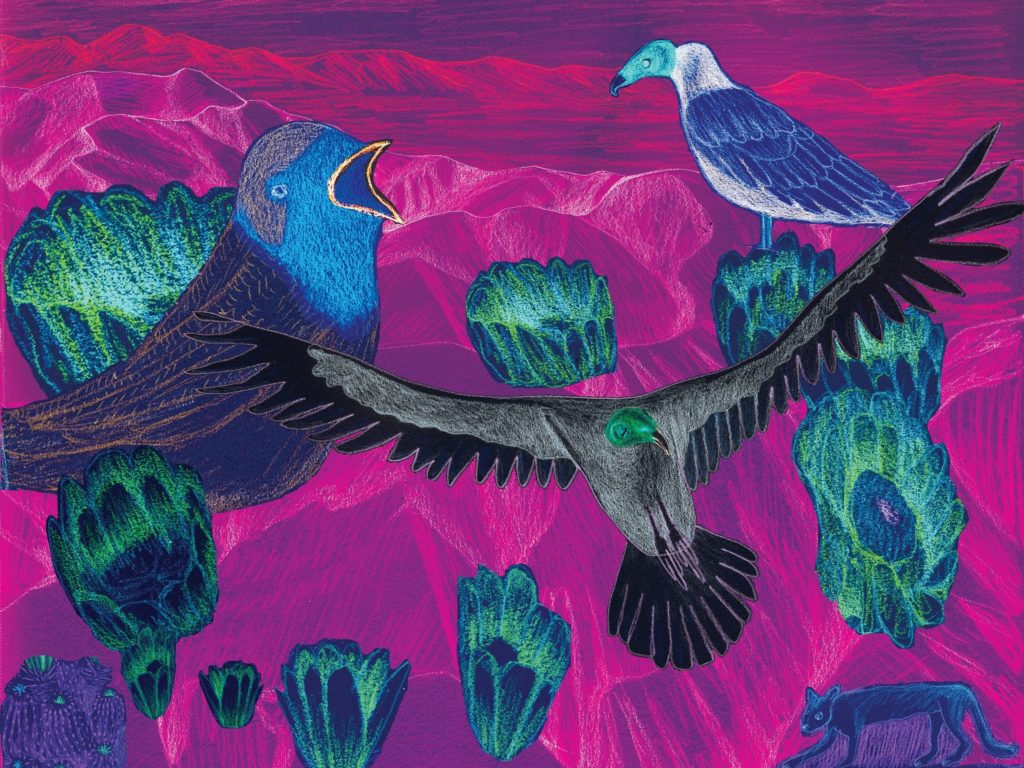

Oak Flat moves seamlessly between settings, and between voices. This motion puts Redniss’ stylistic, empathic, and intellectual gifts on great, and equivalent, display. Redniss draws equal drama from — and pays equal respect to — a Senate hearing and a mining-town mayor’s tales of a shuttered brothel, the heights of Oak Flat and the depths of a collapsing mine. She can switch in a page from the creation of copper roughly 4.5 million years ago to an Apache teenager’s first time on a plane. These transitions work without exception, thanks largely to Redniss’ art. In Oak Flat, she switches between three modes of drawing: borderline-naïve sketches of outer space on black backgrounds; beautiful, wildly colored images of the Tonto National Forest and the mines nearby; and rough, dignified portraits of her subjects on white backgrounds, drawn with such animation they seem ready to rise from the page.

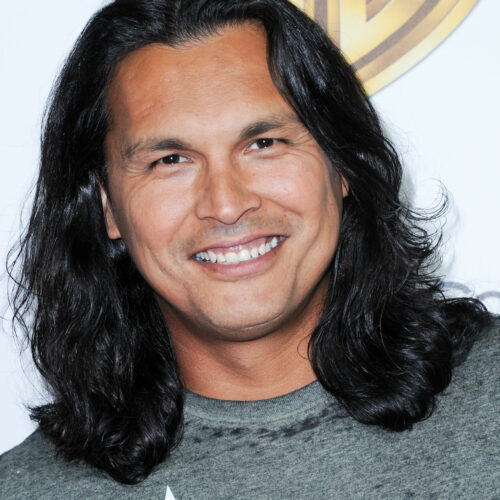

Redniss excels at sharing narrative space with her interviewees. Often, she presents their transcribed statements script-style, not integrating them into her own prose so much as clearing herself out of the way. The teenager mentioned above is Naelyn Pike, a committed activist who, since early adolescence, has worked alongside her grandfather, Wendsler Nosie, to save Oak Flat. Pike and Nosie are as much the book’s narrators as Redniss is. She almost never attempts to explain Apache tradition or religious practice herself, instead ceding the stage to Pike, Nosie, Terry Rambler, or Pike’s mother and sisters. Redniss also includes interviews with a host of pro-mine Arizonans, both Anglo and Apache, though her advocacy for Oak Flat is clear throughout. So is her esteem for Pike and Nosie, who she treats as both collaborators and experts. She defers to their knowledge, their wisdom, and their dedication to Oak Flat. In doing so, she demonstrates significant authorial wisdom of her own.

Redniss’ ability and willingness to erase herself is perhaps more remarkable because she is a highly gifted writer, and a highly flexible one. She can describe a mine with press-release dispassion, or with the lavish detail of Marilynne Robinson evoking an Iowa field. “An open pit mine,” she writes early in Oak Flat, “is as monumental as the Great Pyramids of Giza or Mexico’s Teotihuacan. Spiraling ledges descend into the depths of the mine canyon. Canyon walls shimmer in shades of green, blue, pink, red: malachite, azurite, oxidizing iron.” Below the words is a swirling sketch of the mine, thirteen different colors undulating into what she calls “an enormous gash in the earth.” Redniss rarely flexes these descriptive muscles, though she often draws in this much color. When she combines the two, the effect is arresting. It’s a challenge — in the best possible way — to turn to the next page.

“The Apache believe that Mount Graham is the dwelling place of mountain spirits and a source of supernatural power.” — The Oak Flat

CREDIT: Lauren Redniss/Random House

Oak Flat is no more ordinarily narrative in its structure than its style. It moves willfully through space and time, lingering in small-seeming places — the San Carlos Apache casino, a lookout where teens park to kiss, Wendsler Nosie’s front porch — as much as in grand ones. Redniss seems to stand not only in opposition to the proposed mine at Oak Flat, but to “the attitude of extractive industry — get in, get rich, get out.” On each page, she advocates both subtly and explicitly for patience and respect. She takes to clear heart the fact that the “contested copper under Oak Flat…is older than the earth itself. A mine [there] would operate for about 40 years.”

Oak Flat remains contested. Congress has failed to protect the sacred land there — the late John McCain snuck Resolution Copper’s clearance to mine into a “midnight rider” on a 2014 military-spending bill — but as of yet, the company has not begun digging. Nosie and Pike remain leaders of the fight against the Oak Flat mine and, in 2019, Arizona Rep. Raúl Grijalva introduced the Save Oak Flat Act. Oak Flat is a fervent and beautiful argument in the bill’s favor. It is, one might hope, proof of art’s purpose: to expand minds, to promote beauty, and to make change.

Lily Meyer is a writer and translator living in Cincinnati, Ohio.