Herd Of Fuzzy Green ‘Glacier Mice’ Baffles Northwest Scientists Studying Them

Listen

BY NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE

In 2006, while hiking around the Root Glacier in Alaska to set up scientific instruments, researcher Tim Bartholomaus encountered something unexpected.

“What the heck is this!” Bartholomaus recalls thinking. He’s a glaciologist at the University of Idaho.

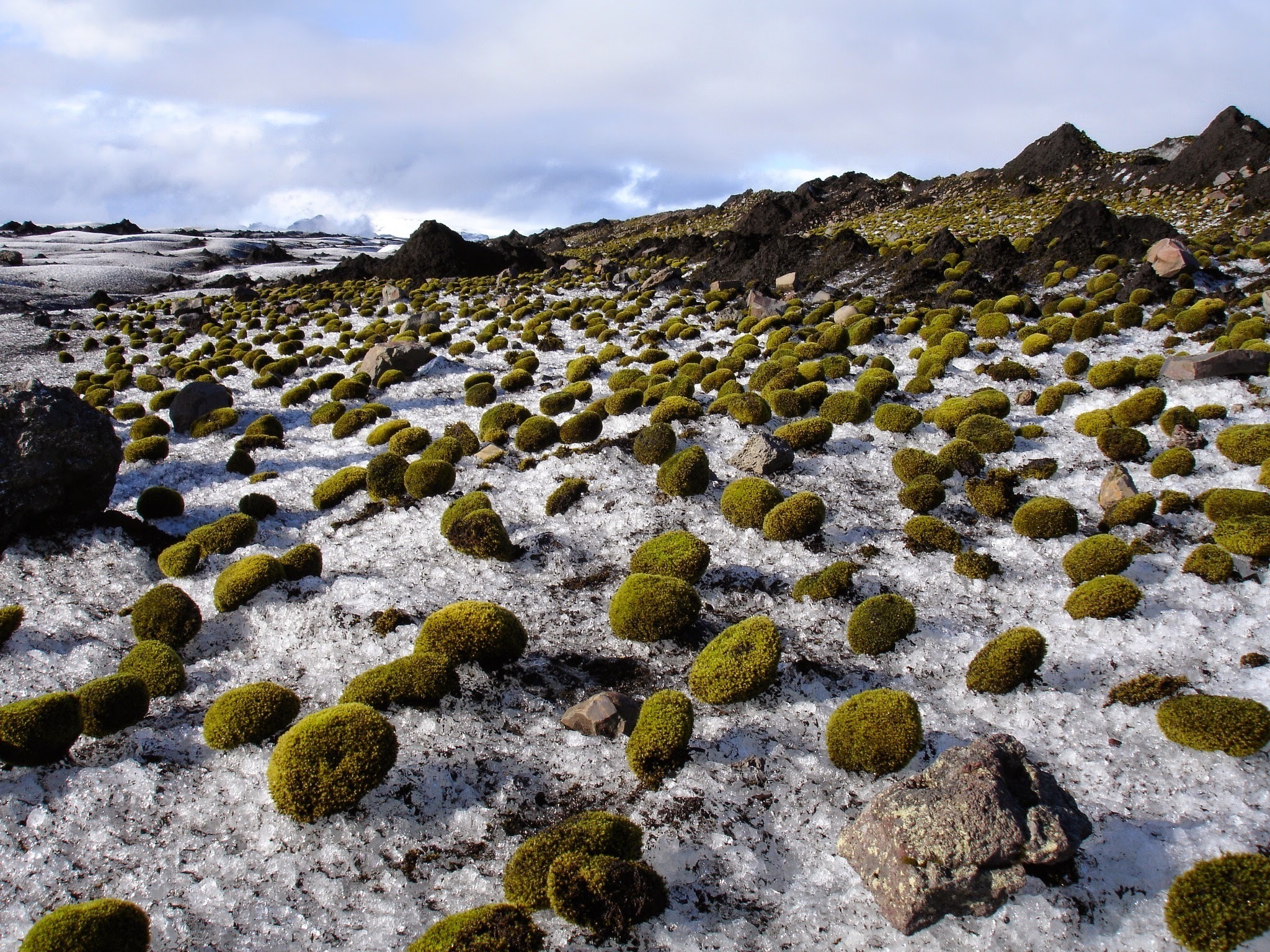

Scattered across the glacier were balls of moss. “They’re not attached to anything and they’re just resting there on ice,” he says. “They’re bright green in a world of white.”

Intrigued, he and two colleagues set out to study these strange moss balls. In the journal Polar Biology, they report that the balls can persist for years and move around in a coordinated, herdlike fashion that the researchers can not yet explain.

“The whole colony of moss balls, this whole grouping, moves at about the same speeds and in the same directions,” Bartholomaus says. “Those speeds and directions can change over the course of weeks.”

In the 1950s, an Icelandic researcher described them in the Journal of Glaciology, noting that “rolling stones can gather moss.” He called them “jökla-mýs” or “glacier mice.”

This new work adds to a very small body of research on these fuzz balls, even though glaciologists have long known about them and tend to be fond of them.

Glacier mice can be composed of different moss species.

CREDIT: Timothy Bartholomaus

“They really do look like little mammals, little mice or chipmunks or rats or something running around on the glacier, although they run in obviously very slow motion,” says wildlife biologist Sophie Gilbert, also at the University of Idaho.

Each ball is like a soft, wet, squishy pillow of moss. The balls can be composed of different moss species and are thought to form around some kind of impurity, like a bit of dust. They’ve been seen in Alaska, Iceland, Svalbard and South America, although they won’t grow on just any glacier — it seems that conditions have to be just right.

Their motion is what interested Gilbert and Bartholomaus, as well as their Washington State University colleague Scott Hotaling.

“Most people who would look at them would immediately wonder, ‘Well, I wonder if they roll around out here in some way,’ ” says Gilbert. “Tumbleweeds come to mind, which are obviously totally different, but also round and roll around.”

She notes that the entire surface of the ball must periodically get exposed to the sun. “These things must actually roll around or else that moss on the bottom would die,” says Gilbert.

The possibility of their rolling had been noted by other researchers, who previously observed that the balls sometimes could be found teetering on a pedestal of ice. That pedestal might form as the moss ball insulated the ice underneath it, preventing it from melting as fast as the surrounding ice. Scientists suspected that the ball would eventually tip off of the pedestal and roll away.

To track the motion of 30 moss balls in Alaska, Gilbert and Bartholomaus tagged each one with a little loop of wire that had an identifying sequence of colored beads. Over a period of 54 days in 2009, they tracked the location of each ball. They returned to check on them in 2010, 2011 and 2012.

“By coming back year after year,” says Bartholomaus, “we could figure out that these individual moss balls were living at least, you know, five, six years and potentially much, much longer.”

The movement of the moss balls was peculiar. The researchers had expected that the balls would travel around randomly by rolling off their ice pedestals. The reality was different. The balls moved about an average of an inch a day in a kind of choreographed formation — like a flock of birds or a herd of wildebeests.

“When we visited them all, they were all just sort of moving relatively slowly and initially toward the south,” says Bartholomaus. “Then they all started to speed up and kind of start to deviate toward the west. And then they slowed down again and progressed even farther to the west.”

The research team tagged each moss ball with an identifying color sequence of beads to track them over months and years.

CREDIT: Sophie Gilbert

The researchers considered several possible explanations. The first, and most obvious one, is that they just rolled downhill. But measurements showed that the moss balls weren’t going down a slope.

“We next thought maybe the wind is sort of blowing them in consistent directions,” says Bartholomaus, “and so we measured the dominant direction of the wind.”

That didn’t explain it either, nor did the pattern of the sunlight.

“We still don’t know,” he says. “I’m still kind of baffled.”

“It’s always kind of exciting, though, when things don’t comply with your hypothesis, with the way you think things work,” says Gilbert.

The work has charmed other glacier scientists who dote on the adorable moss balls.

“I think that probably the explanation is somewhere in the physics of the energy and the heat around the surface of the glacier, but we haven’t quite got there yet,” says Ruth Mottram, a climate scientist at the Danish Meteorological Institute.

She has long admired glacier mice, which she saw while doing fieldwork in Iceland. “They’re extremely engaging when you look at them in a great big mass,” she says. “It’s very hard not to think of tribbles from Star Trek or something like that.”

She expects to see more research on them, as the study of life on glaciers has really taken off in recent years. What was once viewed as a cold, sterile world is now known to be full of bacteria and algae and mysterious life forms.

“I was involved in some research a couple of years ago where we estimated that between 5 and 10% of the melt of the Greenland ice sheet in the summertime is related to the growth of algae and bacteria on the surface,” says Mottram.

Indeed, tiny critters including simple worms and water bears can even live inside moss balls, according to one study from 2012.

Nicholas Midgley of Nottingham Trent University says that back then, he and his colleague Stephen Coulson dissected moss balls and put accelerometers inside a number of them. “From that we were able to deduce that they were actually rotating,” says Midgley.

They did not track where the balls rolled. “That’s obviously where the work that’s been undertaken and published on the Root Glacier advances our understanding,” says Midgley, who notes that “exceptionally few” scientists have ever studied moss balls.

Bartholomaus says he’d like to go back to Root Glacier again and do a good, long hunt for the moss balls that were tagged over a decade ago. He knows that the spot is still loaded with moss balls.

“I did visit them last year,” says Bartholomaus. “I didn’t find any tags during a quick cursory look, but the moss balls are still there. Presumably they’re still rolling around on the glacier, doing their moss ball thing.”

Related Stories:

Richland Lego robotics team hopes state grants won’t be put on hold

Fourth grader Sergio Preciado shows off a Lego shipwreck he helped build and code with his FIRST Lego League team, called the Dino Nuggys. The program is mostly grant funded

Dozens in Yakima rally to support science for national protest

Around 50 people gathered for Yakima’s Stand Up for Science rally on Friday. People around the country attended science protests at the same time. (Credit: Courtney Flatt / NWPB) Listen

Whale, ship collisions around the globe could be helped by slower speeds, study shows

A humpback whale breeches off Half Moon Bay, Calif., in 2017. (Credit: Eric Risberg / AP) Listen (Runtime 1:06) Read Giant ships that transport everything from coffee cups to clothes