Great Recession Recovery Effort Shaped A Key Part Of Joe Biden’s Record

LISTEN

BY ASMA KHALID

In February 2009, the country was in the midst of the worst economic downturn it had experienced since the Great Depression. Unemployment was over 8%, job losses were widespread, and economic anxiety was spreading.

Congress passed a massive economic rescue package, just as it has to avoid economic peril from the coronavirus outbreak, known as the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. It included tax cuts, expanded unemployment support, infrastructure projects and money for a range of Democratic domestic priorities, such as green jobs and high-speed rail.

In total, the package added up to roughly $800 billion.

The person put in charge of overseeing how all that money was spent was the country’s new vice president, Joe Biden. Now that he’s secured the top spot on the Democratic ticket, Biden’s management experience in that crisis may be an important part of his record to voters, as they weigh whether he should replace President Trump, with the impact of the current crisis likely to still weigh on the country in November.

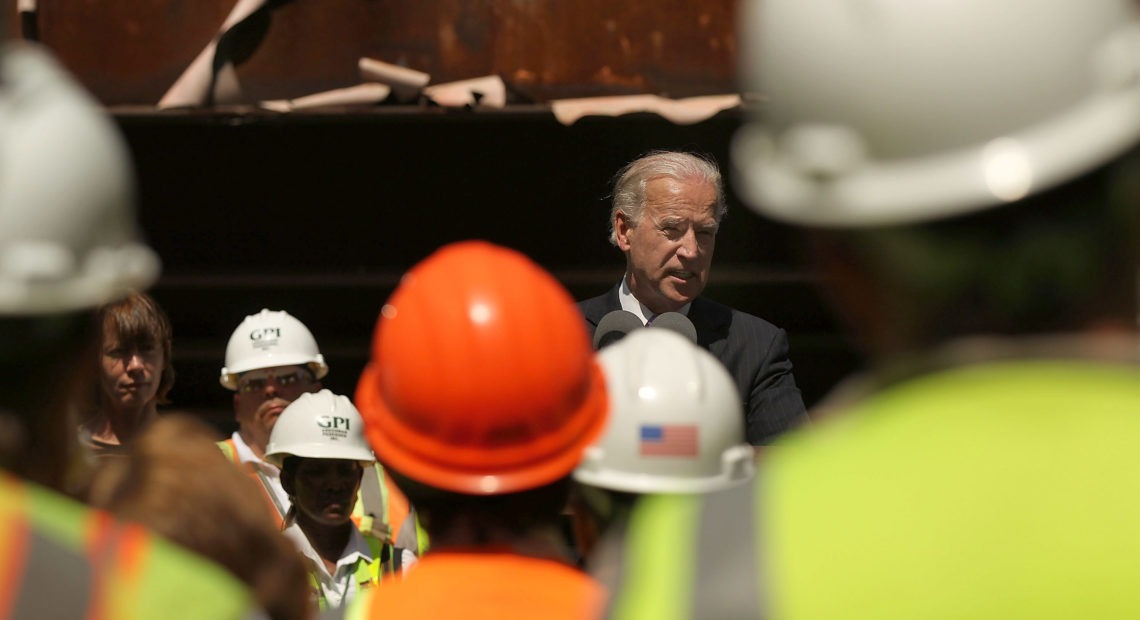

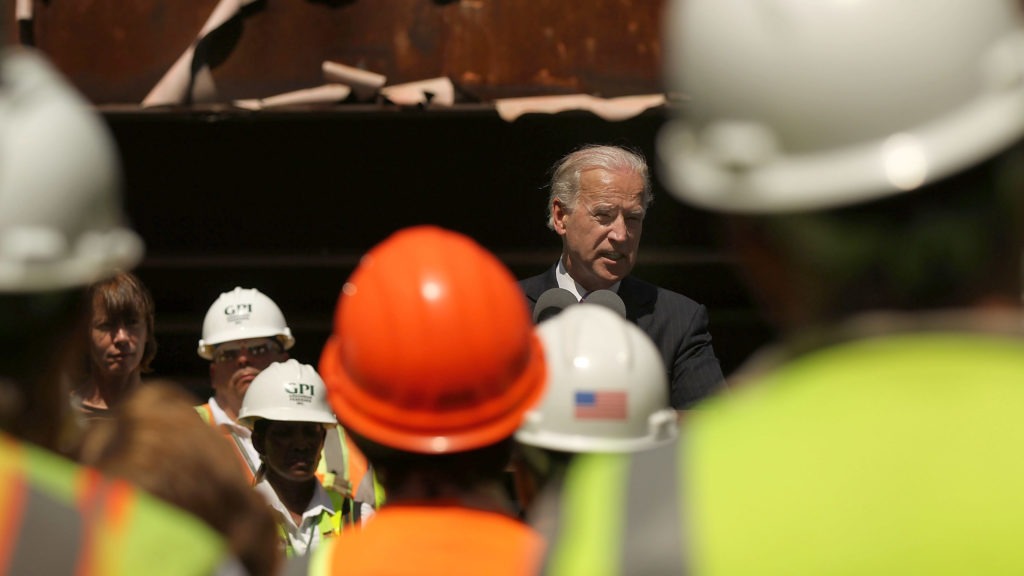

In 2010, Vice President Joe Biden speaks to construction workers at the Brooklyn Bridge, marking a renovation project which was partly funded by money from the 2009 Recovery Act.

CREDIT: Spencer Platt/Getty Images

When President Obama signed the bill, also called the Recovery Act, on Feb. 17, 2009, he thanked his vice president for working behind the scenes to make the legislation possible and then almost immediately handed Biden all the supervision.

Every week, Biden held phone calls with a rotating group of bipartisan governors and mayors.

“The vice president insisted that the recovery implementation office that reported to him, [that] they had what he called the 24-hour rule, which is any question that a governor or a mayor raised got an answer within 24 hours,” said Ron Klain, who was Biden’s chief of staff at the time. Klain continues to serve as an adviser to Biden’s campaign.

Former aides to the vice president say he prioritized accountability and efficiency during the financial crisis.

“He held meetings with the Cabinet as a whole, the various agencies that were part of this, every other week to try to make sure we were moving quickly,” Klain said.

Biden traveled the country to see stimulus projects in action. His real role was somewhat opaque to people outside the White House. He occasionally gave press updates, but Jason Furman, then the deputy director of the National Economic Council, says that wasn’t the vice president’s focus.

“He wasn’t even that much the public face of the Recovery Act,” said Furman. “He was really almost behind the scenes making sure it actually worked.”

Former Biden aides describe the vice president as being obsessed with “implementation.”

“I studied Keynesian economics in grad school, and nobody ever talked about how you’re going to have to try to get governors and mayors to do what you wanted them to with the resources that were coming their way,” said Jared Bernstein, Biden’s former chief economic adviser, who continues to informally advise his old boss. “Probably the most pronounced lesson I took from my work back then is how incredibly mistaken it is to assume implementation. It doesn’t happen by itself.”

It’s the “unsexy” part of the job, he added, which Bernstein now feels is as important as whatever measures Congress actually passes.

Was “Sheriff Joe” too tough?

A few weeks after the Recovery Act passed, President Obama outlined a more detailed job description of what Biden would be doing.

“As part of his duty, Joe will keep an eye on how precious tax dollars are being spent,” Obama said. “To you, he’s Mr. Vice President. But around the White House we call him ‘the sheriff,’ because if you’re misusing taxpayer dollars, you’ll have to answer to him.”

Former Biden aides say transparency and accountability were two principles that anchored their boss.

“I think he took it as a personal affront if any tax dollars were wasted or spent ineffectively,” Bernstein said.

Government estimates found less than 0.5% of the money doled out to contractors was attributed to waste or fraud.

But this fixation on accountability and oversight, while touted by Biden and his aides, came with side effects.

“You could have zero waste, but that would probably mean you’re sending the money out so slowly… that it doesn’t serve the recovery purpose,” said Douglas Holtz-Eakin, former economic adviser to John McCain’s presidential campaign. “I think the Recovery Act was hamstrung by that, and it didn’t work as well as it should have.”

Holtz-Eakin argues that it’s acceptable to make mistakes in the interest of speed when trying to reboot an economy.

“‘Cause if they don’t get the money out, then what’s the point?” he said.

The economic recovery during the Great Recession has often been criticized for being too slow and too small.

Republicans blame Democrats, and Democrats blame Republicans. Liberals argue that they would have preferred a longer, larger stimulus package, but say conservatives didn’t cooperate.

Holtz-Eakin, like many Republicans, also feels the content of the stimulus bill itself was flawed, that it did not focus enough on “stimulating” the economy. It included money for many Democratic priorities, like provisions related to health care IT and renewable energy, that he says weren’t necessary to boost the economy in that moment.

Regardless of which side is correct, the result of their fighting was that the bill was not bipartisan. Not a single Republican in the House signed it. Democrats insist they tried to court Republicans and credit Biden for convincing a few of his former GOP Senate colleagues to cross the aisle and support it. But because of that lack of GOP support in the House, Holtz-Eakin believes Democrats became “more careful” in administering the money, and that made the recovery weaker.

“If it had been bipartisan, and they had held hands and said, ‘This is the thing we ought to do,’ then you aren’t exposed to the Republicans screaming about every dollar that didn’t go right,” he said. “It’s an open question whether the vice president could have done something about that. But that’s what he had to live with.”

Republicans in the House were peeved with the Obama administration as a whole, including Biden.

“The impression from our end was the vice president’s role was something of a joke,” said Michael Steel, a former aide to John Boehner, who at the time was the GOP leader in the House. “Calling him ‘Sheriff Joe’ and promising rigorous oversight of this program, it frankly symbolized that the president’s priorities, his attention, had shifted immediately to health care.”

Steel is referring to the fact that the stimulus was being implemented around the same time that President Obama began pushing for the Affordable Care Act.

Even though Republicans broadly opposed the Recovery Act, Biden’s former chief of staff Klain says many were still eager for a cut of the money.

“No shortage of House Republicans asked for Recovery Act projects in their districts, and the vice president worked with them on that,” he said.

Running on the last recovery

The key political question is what Biden’s role in the 2009 stimulus might mean for the November election.

If the current crisis continues or worsens, it’s plausible the election may be decided by how President Trump handles the coronavirus outbreak and its economic aftermath.

Biden supporters point out that he has a competing record of his own because of his experience.

“He may be the most battle-tested president from the perspective of implementing stimulus plans than anyone I can think of,” said Bernstein.

Even Holtz-Eakin, who was widely critical of the Recovery Act itself, did not take issue directly with Biden. The former McCain adviser now runs the American Action Forum, a conservative think tank, and he suggested that Biden’s experience could be advantageous.

“I think it’s an asset,” Holtz-Eakin said. “He can now in his head think, ‘OK, we’ve got 350 billion [dollars] at the [Small Business Administration], and we’ve got 500 over at Treasury. They’re gonna have this list of problems.’ And he knows that.”