Saving The Legacy Of Rosetta Tharpe, One Of Music’s Biggest Stars, After She Almost Disappeared

PHOTO: Sister Rosetta Tharpe . CREDIT: Tony Evans/Timelapse Library Ltd/Getty Images

NOTE: This story is part of NPR’s ongoing “Turning The Tables” series about women the lives and legacies of women who helped shaped modern music. See the full series here.

BY MARISSA LORUSSO

How does one of the biggest stars in American popular music go missing?

Not physically, of course; despite lying in an unmarked grave for more than three decades after her death, it’s not difficult to locate Sister Rosetta Tharpe today. And during her lifetime, Tharpe was unmissable. As a gospel star in the late 1930s and ’40s, she played at New York hotspots like the Cotton Club, the Apollo Theater and Cafe Society. She toured the country, then the world: In the late ’40s, on the road with The Dixie Hummingbirds, she broke records across the American South; in the ’60s, she met a new generation of adoring fans across the Atlantic. Tharpe was a gospel singer, but she didn’t obey the sacred/secular divide. She fronted Count Basie’s band and jammed with Duke Ellington; her 1944 song “Strange Things Happening Every Day” crossed over to Billboard‘s “race” (known later as “R&B”) charts and, in the ’50s, she even cut a single with a country star. Her (third) marriage was staged in a baseball stadium to an audience of paying fans who numbered in the tens of thousands. She was glamorous, she was charming and she played the guitar like no one else.

But for decades after her career ended, Tharpe was largely absent from popular consciousness. She hasn’t been portrayed by Hollywood actresses in big-budget movies, the way Bessie Smith and Billie Holiday have. Though Johnny Cash, Keith Richards and Bob Dylan all sang Tharpe’s praises, their name recognition quickly surpassed hers. Since her death in 1973, there’s been one biography of her published: Gayle Wald’s groundbreaking Shout, Sister, Shout! in 2007. In it, Wald recounts how Tharpe asked a teenage Richard Wayne Penniman to sing onstage with her in 1945; he said it was “the best thing that had ever happened to me.” Forty-one years later, Little Richard was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame as part of its inaugural class in 1986; Tharpe wasn’t inducted until 2018.

Though it came belatedly, that induction is emblematic of the way Tharpe’s legacy has, over decades, been revived in a gentle swell, one which has grown steadily since the turn of the millennium. Despite that period of silence, Tharpe is now widely understood as a forebear of rock and roll and an iconic force in 20th century American popular music. It’s a precarious resurgence; one predicated on both good timing and deep scholarship, a righteous set of reclamations that often began with mere curiosity buoyed by a cultural shift. It is perhaps a model of the power of the feminist impulse to re-examine the stories we tell in search of the names that have been overlooked, and a reminder of how easy it is, if we aren’t careful, to flatten complicated, paradigm-shifting characters underneath the weight of history.

***

Today, it feels nearly impossible to watch Tharpe play the guitar without recognizing her as a full-on rockstar. There aren’t nearly as many archival clips of Tharpe on YouTube as, say, Mahalia Jackson, gospel royalty who outshone and outsold Tharpe towards the end of her career. But the few that exist show Tharpe playing with flair and flamboyance; laughing and smiling over big, loud guitar solos. “People who don’t know anything about her, when they see the video, they understand it implicitly,” says Wald in a phone call. “They see something going on in the way she holds the guitar, the way she works with it while she sings — they see something that they identify with rock.” The paradox is that even though Tharpe’s performance has all the visible and sonic hallmarks of early rock guitar, the person doing that performing doesn’t fit our expectations of such a pioneer; in other words, as Wald says, “it’s not coming out of a body that they associate with that tradition.” It’s a function, Wald says, of the most obvious marginalizing forces: Rock history is seen as the domain of white guys. But Tharpe also dressed like a gospel singer — high-necked dresses, fur coats — and some of the most recognizably “rock” performances of her career came when she was in her 40s: not the age nor presentation we associate with rock guitarists. “It creates this cognitive dissonance,” Wald says. “They could hear it, and see it, but they just couldn’t put the two together.”

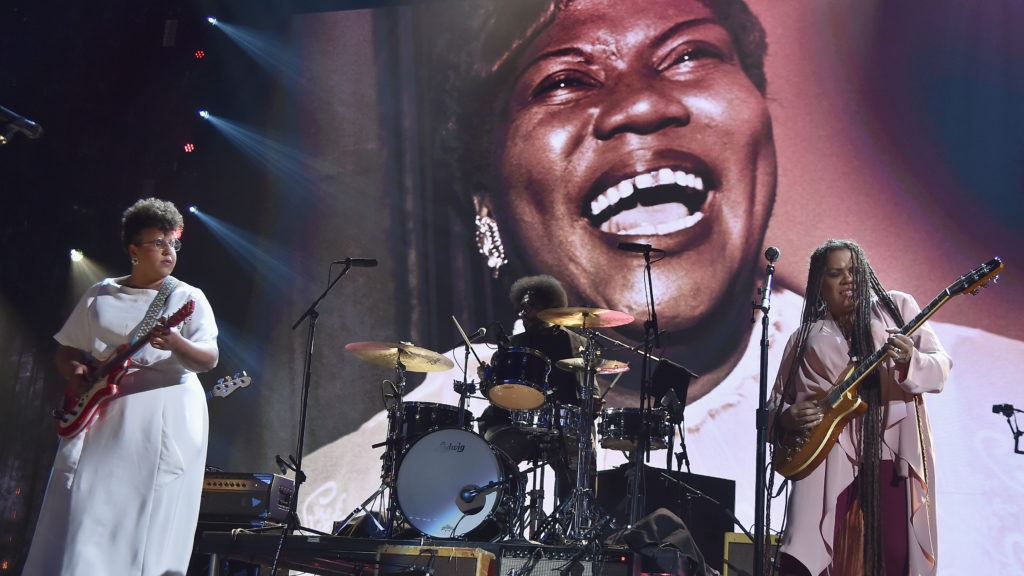

Brittany Howard, Questlove and Felicia Collins pay tribute to Sister Rosetta Tharpe during the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony in 2018. CREDIT: Theo Wargo/Getty Images For The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

Wald was able to put it together, though, the first time she encountered Tharpe, via a video at an academic conference in the late 1990s. She immediately thought, Who is this woman? As she learned more about Tharpe, she intended to use her career as an example in her writing, but found that even colleagues in her academic circles would need background information about the musician whenever she’d mention her. And in terms of other academic material, Wald says, there “was nothing of any length,” besides some writing about her within gospel scholarship.

Popular culture at the time was not much better-versed in Tharpe’s story. When Tharpe died in 1973, her obituary in the New York Times calls her “one of the first gospel singers to gain wide recognition outside the Negro churches of the Deep South.” Her guitar playing isn’t mentioned, though the article notes the criticism she faced for putting “too much motion as well as emotion into her singing” — a style of performing which would set the template for many early rock singers.

For decades after that, her name was more or less absent from the mainstream press and music publications. When she was mentioned, it was often as a footnote in the story of other, better-known artists. Tharpe came up occasionally as a foregone gospel icon (lists beginning with “artists like” and including Clara Ward and Mahalia Jackson are a good place to find her); she was mentioned a handful of times as an influence on Little Richard, and in the obituaries of other early-20th century musicians she played with. The compilation Sincerely, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, released in 1988, got some press. But you can’t, for example, find many adoring retrospectives of her greatest works or appreciations of her influence published in major magazines on the anniversary of her death. (The United States Postal Service did, however, issue a stamp in her honor in 1998, along with other gospel singers, as part of its Black Heritage series.)

But by the time Wald saw that video, the seeds for Tharpe’s revival were, in many ways, already in place. A decade or so earlier, young black musicians had founded the Black Rock Coalition to promote the work of black musicians and combat stereotypes that marginalized the role of black artists in the development of American popular music — rock and roll very much included. And the ’90 also saw increased space in the cultural mainstream for conversations about women in rock history, including women instrumentalists. The riot grrrl movement was in full swing, and bands like Bikini Kill, Bratmobile, Heavens to Betsy and others not only provided models of contemporary women guitarists but made it a point to call out their foremothers. The riot grrrls saw themselves not (only) as groundbreaking musicians but as part of a lineage of women rock artists. That legacy has lived on; the early 2000s saw the proliferation of summer camps intended to teach girls how to play rock and roll, and Tharpe’s name is often mentioned at them.

At the same time, feminist music critics and scholars were continuing to demonstrate the importance of women’s voices in popular music history. In 1992, Gillian G. Gaar published She’s a Rebel: The History of Women in Rock and Roll; in 1995, there was Rock She Wrote, a groundbreaking collection of women writing about rock, pop and rap. And in 1997, Rolling Stone published its Book of Women in Rock: Trouble Girls, which included the work of nearly 50 women writers.

All of this created a moment where genuine interest in Tharpe’s legacy seemed possible; as Wald says, “there was already a politicized cultural framework for thinking about her existence.” And there was another musical bridge under construction between Tharpe and the rock canon: Gospel — which had always made more space for Tharpe as a foremother anyway — was experiencing crossovers of its own. The idea of what gospel music could sound like had expanded dramatically between the 1970s and the early 2000s. Wald cites, as one example, the rise of Christian hip-hop, which started in the mid-80s with artists like Stephen Wiley and Michael Peace (and can be traced through to the success of mainstream hip-hop artists like Chance the Rapper and gospel rappers like Lecrae, whose 2014 album debuted at No. 1 on the Billboard 200 and gospel charts). This new sonic space made it easier to imagine that a guitar-playing gospel singer from the early 20th century might also be relevant to musical traditions outside the church.

In 1992, when Johnny Cash was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, he mentioned Tharpe when speaking about rock’s early influences on him. He remembered buying records as a kid: “It was at the Home of the Blues record shop where I bought my first recording of Sister Rosetta Tharpe singing those great gospel songs,” he said in front of the Rock Hall crowd. “Some of the earlier songs I wrote were influenced by people like Sister Rosetta Tharpe.” Cash, clearly, took for granted that Tharpe’s name would be relevant to an institution dedicated to the history of rock and roll; it would still be another 26 years before she was inducted.

***

By the early 2000s, the tide was beginning to turn. In 2003, MC Records released a tribute to Tharpe called Shout, Sister, Shout! featuring an all-star lineup of women musicians: Joan Osborne; Maria Muldaur accompanied by Bonnie Raitt; Sweet Honey In The Rock; Odetta; Janis Ian and more. It also included Marie Knight, Tharpe’s longtime musical partner. The tribute came together after rockabilly musician Sleepy LaBeef played Tharpe’s music for Mark Carpentieri, president of M.C. Records; Carpentieri said hearing the music felt like “a revelation.” That same year, Universal released a CD called The Gospel Of The Blues, featuring 18 of Tharpe’s Decca tracks from between 1938 and 1948 that demonstrate the way her gospel sound crossed over to blues, R&B, swing and more. The Blues, a documentary film series produced by Martin Scorsese, also came out in 2003; it also featured a clip of Tharpe performing.

Internet search traffic reflects this slow creep of revival, too; Google Trends only goes back to 2004, but you can see a steady increase in searches about Tharpe since it began its tracking. There’s a peak in 2009, for example, when Tharpe finally got her headstone. Bob Merz, a Philadelphia-based writer and publisher, had seen a TV interview with Wald that mentioned her lack of headstone; it motivated him to organize a benefit concert to pay for the memorial. The epitaph, written by Tharpe’s longtime friend Roxie Moore, reads, “She would sing until you cried and then she would sing until you danced for joy. She helped to keep the church alive and the saints rejoicing.”

There’s another spike in 2013, when an episode of American Masters about Tharpe, called “The Godmother Of Rock and Roll,” aired. In a filmmaker interview for PBS, writer, producer and director Mick Csaky said he was inspired to make the film after seeing an interview with Wald that featured footage of Tharpe performing. But he was finally convinced to pursue the project after he heard a clip of Bob Dylan talking about Tharpe on his Theme Time Radio Show. Csaky says Dylan gave the impression Tharpe was one of “the most important influences in popular music in the 20th century.” In that interview, Csaky says viewers often see Tharpe for the first time and tell him she’s “just like Jimi Hendrix, Pete Townshend, Eric Clapton” — he tells them they’ve got it backwards. They sound just like her.

In the last five years, blog posts have been popping up that position Tharpe as a perpetually undersung trailblazer, especially for queer women and black rock artists. Some from just the last year have titles like “Before Hendrix, Elvis and Chuck Berry, There Was Sister Rosetta Tharpe” and “queer, black & blue: sister rosetta tharpe is muva of them all” and “What Do You Mean You’ve Never Heard Of Sister Rosetta Tharpe?” This month, at Fashion Week in New York, fashion brand Pyer Moss showed off its Spring 2020 collection, the final installment of Kerby Jean-Raymond’s “American, Also” series. The show’s title is “Sister;” it features images of Tharpe emblazoned on dresses, boots and pants.

There is, too, the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame induction in 2018. A video produced to celebrate her nomination — this was the first time she was nominated, though she was arguably eligible from the moment the criteria was invented — hints at how, despite the honor, Tharpe’s legacy is still so stubbornly underestimated. “Her heartfelt gospel folksiness gave way to her roaring mastery of her trusted Gibson SG,” a voiceover says, “which she wielded on a level that rivaled the best of her male contemporaries.” But Tharpe didn’t rival her male contemporaries; she schooled them. She inspired them. She took them to church, and to the club, and to the birthplace of an entirely new style. Still, when it was announced in December 2017 that she would indeed be inducted within the “Early Influences” category, it felt like it represented a kind of justice.

***

In the interview about his documentary, Csaky chalks up the fact that so few people knew about Tharpe for so long as “a case of her simply falling through the cracks of history.” Anyone who looks for systemic bias in our cultural creation myths knows it’s not quite that simple, that irrelevance more eagerly awaited someone like Tharpe than would ever await Elvis. Because by the time “rock and roll” became something concrete — a knowable, definable style or ideal – it had hardened into something that had no place for her. “Rock and roll,” by definition, wasn’t for women to play – just look at the all-male inaugural class of the Rock Hall. It wasn’t concerned with the sacred-secular divide, and so it wasn’t impressed by someone who learned how to navigate it to her advantage. (Unless, of course, you count Aretha Franklin, who surprisingly was inducted in 1986.) The style and flamboyance of rock and roll, it had been decided, didn’t include that of a guitar-wielding, praise-shouting, god-fearing woman like Tharpe. She had an utter unwillingness to abide by the strictures her gender, race and genre set forth, and she made music that defied easy categorization. Those qualities made her — and her music — unique and inspiring enough to kick start the global musical revolution of rock and roll, the dominant popular American musical form for decades and one that continues evolving to this day. The great indignity is that those very qualities also made it so easy to erase her from the story she helped create.

At the Rock Hall ceremony, Tharpe’s legacy was celebrated in a performance by Brittany Howard, who called Tharpe’s induction “long overdue” and was joined onstage by Felicia Collins and Questlove. Howard nails Tharpe’s soul-saving charisma as she sings “That’s All;” watching her and Collins trade guitar riffs feels like a glorious moment of sisterhood. That these women’s careers exist at all, you could argue, is thanks to Tharpe. “She plugged in that electric guitar, and she started rock and roll,” Howard says in another promotional video from the Rock Hall.

It was not a straightforward path that led Tharpe from Cotton Plant, Ark. to the heights of fame, towards cultural anonymity and then into the halls of an institution that couldn’t have existed without her pioneering work. But perhaps Tharpe, who played by no rules but her own, would have expected it no other way. It’s not possible, now, to undo the half-century of erasure Tharpe faced, to know what popular music today would look like if generations of artists had grown up knowing her name and learning her riffs. Perhaps we’d have a rock and roll museum made in her image, with countless musicians hoping to pay tribute to Tharpe on its opening day. Perhaps her spotlight would lead us towards other untold stories. We can’t know. We can, however, keep telling a different story – a truer one, one where rock and roll starts in Cotton Plant. Or better yet: We can admit that there’s still so much we don’t know; there are likely many other marginalized trailblazers waiting for us to hear them. Maybe that’s the truest story about rock and roll we can tell.