Constructing Jazz Inside Fine Art, And Vice-Versa

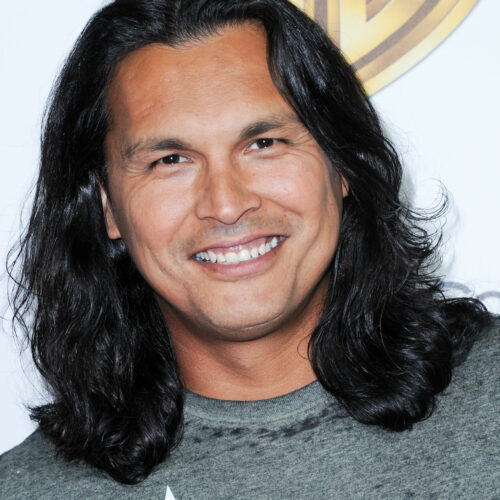

PHOTO: Jason Moran, Slugs’ Saloon, 2018. CREDIT: Farzad Owrang/Courtesy of Jason Moran and Luhring Augustine

BY NATE CHINEN

For many observers of modern jazz, pianist Jason Moran became a known entity 20 years ago, with the release of his debut album. For Adrienne Edwards, curator of performance at the Whitney Museum of American Art, his name first circulated more recently, as a kind of rumor.

“I have really good friends who are artists — whether it’s Adam Pendleton, or Julie Mehretu, or Kara Walker, or Ryan Trecartin and Lizzie Fitch — that were all saying, ‘I want to work with Jason,’ ” Edwards reflected this week. “And I kept going, ‘What is it about this musician doing things that are much broader than music? What is it about him that they are drawn to?’ ”

The answers can be found, if not entirely resolved, somewhere in Jason Moran, a pathfinding exhibition that opens this Friday. It’s the first full show presented at the Whitney by Edwards, who originated it (with another curator, Danielle Jackson) last year at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. And, in addition to consolidating a large swath of Moran’s interdisciplinary work, the show highlights how his jazz skillset — not just with improvising, but also with nuances of alchemy and flow and surprise — have opened new possibilities for the artists in his orbit.

“Everyone had different reasons for seeking him,” Edwards says of those artists, “but the commonality was definitely aesthetic. Trying to get to a feeling of something that they knew, in their own work, they hadn’t fully gotten to yet.”

Moran, 44, grew up in an art-literate family in Houston, Tx., but he traces his current depth of engagement to two apprenticeships, with revered performance artist Joan Jonas and visionary conceptualist Adrian Piper. “You will hear me talk about Adrian Piper with as much vigor and respect as Wayne Shorter,” he said in a museum conference room on Tuesday. Responding to a question about when the chute fully opened to the art world, he looked back to 2006: “Making Artist in Residence for Blue Note, and putting Adrian and Joan on the record. That was me saying: ‘They are like Sam Rivers in my recording catalog. They are that important.’ ”

Five years ago, Moran ended a long association with Blue Note, asserting ownership of his music while also signaling a shift in focus. He joined the roster of a gallery, Luhring Augustine. He also started his own label, Yes Records, breaking in its catalog with an album by his wife and collaborator, mezzo-soprano Alicia Hall Moran. (As a team, the Morans have created major concert programs and other projects — including BLEED, a performance residency at the 2012 Whitney Biennial.) Subsequent releases on Yes Records have included Music For Joan Jonas, a collection, and MASS {Howl, eon}, after a work made with Mehretu.

Jason Moran maps some, but inevitably not all, of these past collaborations. Luanda-Kinshasa, a transfixing film by Stan Douglas, occupies a small gallery. A six-hour loop of hallucinatory realism starring Moran and a handful of other real-life improvisers as 1970s funk shamans, it was previously shown at the David Zwirner gallery, and partially released on vinyl.

Other collaborations are represented in a video compilation, projected in a loop on three walls of the main gallery space. Unsurprisingly, this feed works best with pieces designed for such a medium — like “Chess,” a three-channel installation by Lorna Simpson in which Moran fills one mirrored frame while the artist inhabits the others, in cryptic costumes. Another standout is a harrowing Kara Walker shadow-puppet film, part of a series titled The Bureau of Refugees, whose power derives in part from a tensile score by Moran and Hall Moran.

The room housing these videos is also home to three sculptural set pieces from a project Moran calls STAGED, which most visitors will understand as the central feature of the show. Conceived as living remnants of mythical New York jazz venues, two of these hulking works — conjuring Harlem’s Savoy Ballroom in the swing era and The Three Deuces on 52nd Street at the height of bebop — were commissioned by Okwui Enwezor for the 2015 Venice Biennale.

In the illuminating museum catalog for Jason Moran, published by the Walker Art Center, Enwezor (who died earlier this year of cancer) notes that even in their vacant quietude, these pieces hum with tensions. “Moran’s constructions are like spirit catchers,” he writes, “meta-spaces where African American emancipatory struggles for political autonomy, social wholeness, and creative rebellion are evoked and memorialized.”

Those echoes of conflict are even more present in STAGED: Slugs’ Saloon, which was commissioned for the Walker show. Slugs’ was a rugged outpost in the far East Village, infamous in jazz lore as the spot where trumpeter Lee Morgan was murdered in 1972. That’s not a leading concern for Moran, who has an ongoing affiliation with saxophonist Charles Lloyd, another Slugs’ alum. Still, it’s hard not to read a trace of violence into the kicked-over chair at the center of the sculpture, beside a glowing but blank-faced Wurlitzer jukebox.

Moran says that with STAGED, he’s reaching beyond the disembodied sound of jazz recordings, considering other ways in which the music’s history has been encoded. “Though I think of these places as so remarkably documented through these records,” he says, “there’s still a gap in the conversation around them. And in museums, you make a thing to display it.”

For those who know jazz history, Moran’s three pieces also lob an implicit commentary on the shifting economies and social realities of the music — its movement from a popular entertainment to an underground art music, and in and out of black artistic control. The Savoy was a space for dancing, and a magnet for white fans venturing uptown. The Three Deuces packaged bebop for hip consumption. Slugs’ was a dive where transactions were often made off the books. That all of these bygone spaces are now being memorialized in a museum exhibition, with all the resources and cachet such a thing entails, is part of Moran’s critical calculus.

In addition to his assemblages, Moran has works on paper in the exhibition, mainly from a series titled Run. Made by taping scrolls across the piano keyboard, and then playing the instrument with charcoal or pigment on his fingertips, these pieces feel charged with kinetic intention. They’re reminiscent of the basketball drawings of David Hammons, and of text paintings by a frequent Moran collaborator, conceptualist Glenn Ligon. “In the glimpse of that front gallery wall,” says Edwards, “you see an entire arc of Jason as a draftsman. They’re these really beautiful private improvisations; it’s him, in his own space, which we don’t see.”

At a reception for Jason Moran on Tuesday night, the opposite was true: Moran was ubiquitous, greeting friends and admirers as he moved through the space. Then it was Go Time: along with bassist Tarus Mateen and drummer Nasheet Waits, his longtime partners in The Bandwagon, he stepped into the set of The Three Deuces and started into an exploratory performance.

Starting out with a group improvisation, they soon settled into “Refraction,” a piece Moran recorded in two versions on Artist in Residence, with and without Joan Jonas. The rustle and tumble of the band, which has become an identifying trait, sounded at home in the room. After moving into another theme, Waits took a drum solo — giving Moran and Mateen the chance to walk across the gallery, through the crowd, and take up new posts at Slugs’ Saloon.

The Whitney will see a lot more like this in the weeks to come, by way of a performance series titled “Jazz on a High Floor in the Afternoon,” after a remark made by Hammons. Slated to begin next Friday, Sept. 27, with a rare performance by saxophonist Archie Shepp, it will also include vocalist Fay Victor (Oct. 18-19), saxophonist Oliver Lake (Oct. 25-26) and pianist Joanne Brackeen (Nov. 22-23). Each artist will be free to utilize whichever space they like.

The Bandwagon will mark its 20th anniversary as part of the exhibition, with ticketed concerts on Dec. 19, 20, and 21. But before then, the trio will play its annual Thanksgiving-week engagement at The Village Vanguard, a room that has become as sacred and spiritually charged for Moran as any of the haunts in STAGED. That he’ll be working there during his exhibition seems fitting, as a reflection of the real-life work that his art evokes and cannily distorts.

Inside the Wurlitzer jukebox on the Slugs’ Saloon set, invisible to any observer and unmarked on the menu, there’s a 45-rpm record that Moran had made for the occasion. It’s a recording of audience banter between sets at The Village Vanguard, during one of his recent engagements.

“You won’t ever hear it,” he says. “It’s the audience in there just talking, with some music lightly playing in the background. So yes, there’s a record in there.” He laughs. “Someone I met told me there was a guy who used to whistle all of the solos on the jukebox at Slugs’. I don’t even know if that’s real. But that record is for him.”