Ella Fitzgerald: The Voice That Shattered Glass

NOTE: This story is part of NPR’s ongoing “Turning The Tables” series about women the lives and legacies of women who helped shaped modern music. See the full series here.

LISTEN

BY MICHELLE MERCER

It’s the stuff of legends: an urban legend and a jazz legend combining into a legendary advertising campaign.

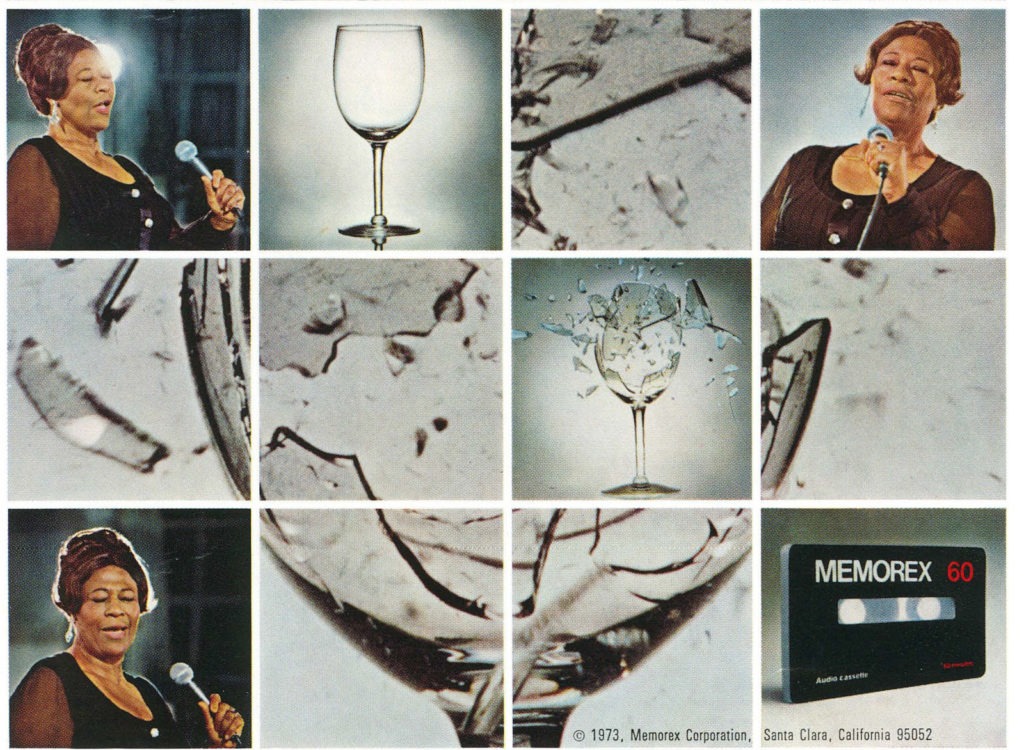

In 1970, the Leo Burnett ad agency in Chicago had an imaginative idea for selling Memorex’s new line of blank cassette tapes. They’d prove the old myth that an opera singer could shatter a wine glass with a high note — and then claim a Memorex cassette had such exacting sound precision that its recording of the singer could break a glass, too. Leo Burnett made a couple TV commercials with this theme featuring tenor Enrico di Giuseppe and soprano Nancy Shade. The tagline: “Memorex Recording Tape … Reproduction so true it can shatter glass.”

It was a good enough start, but opera was too elitist for Memorex’s larger aims. After first reaching out to audiophiles — early cassette advertising was placed in magazines like Hi Fidelity and Stereo Review — the company wanted to target a broader demographic with TV commercials aired during football games on CBS. The glass-breaking cassette campaign needed a spokesperson whose musical style embodied a more casual brilliance.

Enter Ella Fitzgerald: jazz legend, gold standard for vocal excellence and paradigm of high fidelity sound, thanks to her influential mid-century recordings. Music historian Judith Tick, who’s finishing a book about Fitzgerald, says the singer’s career was a perfect fit for the campaign, as she was known at the time “not only as a legend, but as a treasure-bearer of American culture.” Her immense body of work began in the 1930s, peaked in the 1940s with the bullseye pitch accuracy, vocal range and sheer originality of her scat singing innovation, and then peaked again with her definitive 1950s and early 1960s songbook interpretations of Gershwin, Rodgers and Hart, Cole Porter and others.

Ella Fitzgerald, photographed in 1940.

CREDIT: Gilles Petard/Redferns/Getty Images

In a 1985 interview, Fitzgerald remembered her Memorex audition at the Algonquin Hotel in New York: “They asked me to do the ending of ‘How High the Moon.’ I just kept singing, ‘High, high the moon,’ doing the ending. And when the glass broke, they said, ‘That’s the one!’ Then I got the job. … A lot of people say, ‘Did you really break the glass?’ We had to prove that. They had lawyers there.”

So in 1972, at age 55, Ella Fitzgerald became the spokesperson for Memorex cassettes. These commercials came at an important juncture in both Fitzgerald’s career and in jazz. After decades as the First Lady Of Song, Fitzgerald faced a time when traditional jazz was declining in popularity. But as the Memorex campaign became an institution, it fueled a career revival that helped to extend her relevance in new ways, and eventually positioned her to hand off the baton to the next generation.

In the campaign’s earliest TV spots, Fitzgerald scat sings, hits a high note and shatters a goblet. As countless sound engineers and a 2005 Mythbusters segment have proven, breaking a glass wouldn’t have been an unlikely feat for Fitzgerald, especially with her voice amplified. Most glasses resonate at a frequency around high C; with Fitzgerald’s two-octave range, hitting that note would have been no problem. Just as critical to Fitzgerald’s authenticity in the campaign is her unreconstructed middle-aged appearance: her wig, round body — and in some spots, cataract-correcting eyeglasses — lend warmth and conviction to her televisual style. The iconic Fitzgerald comes across as so real in the commercials that her mere presence authenticates the ad’s claim of a Memorex cassette recording breaking a glass. “Is it live or is it Memorex?” the ads ask. What matters is that it’s Fitzgerald onscreen.

Dizzy Gillespie famously said that Fitzgerald could sing back anything he played on the trumpet. If the commercial’s message hinged on her ability to leave a goblet in shards, her scat singing carried weight in the spot, too. “It means improvisation, it means freedom,” says Tick. “So when you have Ella scat sing, the epitome of this great improvisatory skill, it just reinforces something about jazz that speaks to young people and speaks to all of us: It’s a magical craft. And that magic about scat carries over to the magic of the glass shattering.” Fitzgerald’s scat singing also played to the idea of consumers making their own recording copies and mixes, improvising their own musical experiences onto blank cassettes.

In 1974, Memorex introduced a new TV spot and angle for the Fitzgerald campaign. Count Basie, Fitzgerald’s old bandmate, sits with his back to a recording booth, listening for the difference between Fitzgerald’s live voice amplified through speakers and a Memorex tape recording of it. “You gotta be kidding, I can’t tell!” he says, as if in on an elaborate joke. Fitzgerald or cassette recording? If jazz royalty like Count Basie can’t tell and doesn’t care, why should we? Consumers can only deduce that playing a Memorex tape is interchangeable with having Fitzgerald sing in their homes. Hearkening back to man vs. machine fables, to John Henry against the steam-powered drill, the message in this spot is that human expression and cassette technology can come together for the win.

An “Is it Ella or is it Memorex?” ad from 1973. CREDIT: Memorex At 50

It couldn’t seem quainter today: Memorex’s appeal to audio sophistication with a TV listening stunt, all to sell a recording format that’s long been outmoded. But veteran recording engineer Jim Anderson says it’s not so improbable that Count Basie or his Memorex commercial successor, jazz arranger Nelson Riddle, might have failed the “Ella or Memorex” test. The trick is, they’re not in the room with Fitzgerald. Anderson says the musicians were likely in the control room, hearing a “live playback of the musicians in the studio, or a tape of that same performance” — which, he argues, could be “pretty convincing.” He adds that Count Basie and Nelson Riddle were over 50 at the time; after long careers spent in front of live bands, and their hearing probably “wasn’t as sharp as it would have been … 20 or 30 years before that.” With cassette companies selling ever-improving quality throughout the 1970s — noise reduction, corrections to “wow and flutter,” those pesky tape fluctuations in pitch and tone— the technology would have seemed cutting-edge to many consumers.

In his spot with Fitzgerald, Nelson Riddle lacked Basie’s ironic twinkle, displaying some awkwardness in the role. It hardly mattered. In the era of three-network TV, Memorex commercials aired on both CBS and NBC during football games and rock shows. Anyone who watched television at all was likely to catch an Fitzgerald Memorex spot. The “Is it live or is it Memorex?” campaign and tagline became a branding success on par with Maxwell House’s “Good to the last drop” or Timex’s “It takes a licking and keeps on ticking.”

As the campaign became an institution, Fitzgerald, pushing 60, reveled in a Memorex-fueled career resurgence. As the critic Leonard Feather wrote, “Ella Fitzgerald’s pitch for Memorex probably did more for her than a hundred concerts.” Fitzgerald’s career revival came at a time of critical anxiety around the idea of “selling out,” thanks in part to the declining commercial success of traditional jazz and the popularity of fusion bands, like Herbie Hancock’s Headhunters. For some jazz purists, using the art form to hawk cassettes on TV amounted to a capital offense. One jazz critic went so far as to call Fitzgerald a “freakish cultural icon” for her glass-shattering Memorex turn.

Fitzgerald was indifferent to stylistic boundaries and popular anxieties. Her career dated back to the 1930s, when jazz was mainstream music. Fitzgerald had made onscreen appearances since 1942, when she sang her breakthrough hit “A-Tisket, A-Tasket” in the film Ride ‘Em Cowboy. “She always wanted to reach as many people as possible,” says Tick. “So for her, reaching out to a mass public was not any kind of handicap. It was what she would want to do.” Mainstream appeal had distinct value for artists of color, Tick adds: “Ella and Basie both know how great it is for black singers and black artists to be given this chance to endorse such an important product that is mainstream. We know that black artists were kept off the radio and television. It changes in the 1970s, because we’re in the post-civil rights era and the prestige of black is beautiful, black pride, black culture is emerging. And that means there were black celebrities by the end of the ’70s who [were] doing all kinds of endorsements.”

By 1975, Memorex’s MRX2 was the best-selling cassette tape in the United States. Still, there was stiff competition from rival companies like TDK and Scotch, which would enlist Stevie Wonder and Ray Charles as spokespeople in the late ’70s. As Memorex marketing manager Jack Rohrer told Billboard in 1976, the company needed to “capture the attention of younger tape users who are just learning to appreciate cassettes.”

So Memorex produced a fresh commercial teaming Fitzgerald with Melissa Manchester, a rising 25-year-old singer-songwriter best known for the hit “Midnight Blue.” Manchester had sung backup for Bette Midler in the Harlettes and worked as a staff songwriter for Warner-Chappell. And she’d been a devoted Fitzgerald fan from the moment she heard the singer’s Gershwin songbook album as a little girl. “I had no idea what she was singing about, but I decided there and then that I wanted to live where she lived. She just was my guiding light through my whole life,” she says. “When I first got to meet her on the set of the Memorex commercial, she was so jolly and so dear and so huggy. I immediately felt confirmed of all I had hoped for: that she was just magnificent in every way.”

In the spot, Manchester was thrilled to flunk what she now recalls as a “kosher” “Ella or Memorex” listening test. “Nobody’s perfect!” quips Fitzgerald, embracing Manchester.

In the ad, Fitzgerald seems fully herself onscreen — and in this spot’s generational scheme, that signature warm, matronly appearance had special meaning. Manchester, meanwhile, recalls wearing she considered appropriate attire, a loose blouse and jeans, but was called off the set after a take or two. “My manager said to me, ‘The producer would like you to put tape over your nipples for the next shoot,'” she remembers. In the mid-70s, a braless style was trendy and would have resonated with younger consumers, but Manchester wasn’t allowed to sport that look. However, Fitzgerald was granted her usual autonomy of self-presentation.

“I think Ella becomes a kind of maternal figure in that ad,” Judith Tick says. “She’s passing the torch to Melissa Manchester. Not the torch of jazz, but the torch of endorsing Memorex or the torch of purity of tone.” As the commercial aired on TV, Manchester’s rich, dramatic voice became a radio staple on ballads like the Ice Castles theme song “Through the Eyes of Love” and her 1979 hit, “Don’t Cry Out Loud.”

With the advent of the car cassette deck, Sony’s release of the first Walkman and the growing phenomenon of mixtape sharing, cassette sales were very much on the rise at the end of the ’70s. But the Fitzgerald Memorex partnership showed signs of wear. A 1979 Memorex spot featured Fitzgerald opposite jazz flugelhorn player Chuck Mangione, who performed “Feels So Good,” his rare instrumental hit.

Here the roles are inverted: Fitzgerald sits outside the booth listening for the difference between Mangione’s live performance and a cassette recording.

Though this version with Mangione aired widely, Fitzgerald’s transition from live singer to passive stock icon implied her obsolescence. The generational shift initiated in the Manchester spot is completed here, with Mangione’s youthful enthusiasm and trendiness overshadowing Fitzgerald’s classic appeal. The campaign had run its course. And as popular as cassettes were becoming, they accounted for less than 15 percent of Memorex’s total sales. The company’s deep losses in the early ’80s would prompt the sale of its consumer business, including its cassette campaign, in 1982.

For most of a decade, the Memorex commercials presented Fitzgerald as an exemplar of sound fidelity, model of authenticity, and most significantly, her own artist. Fitzgerald’s peer Billie Holiday had her tragic legend overtake her art in the broader culture. In contrast, Fitzgerald’s late-career Memorex ads put her inimitable style and voice right at the center of her popular reputation, helping to grow the legend of her art itself.

The commercials made Fitzgerald into a folk hero synonymous with cassette technology. Children on the street called out to Fitzgerald as “The Memorex Lady,” to her delight. She’d tell of airline pilots warning her not to sing on their flights for fear of broken plane windows. The ad campaign capitalized on a folk legend about the human voice’s glass-breaking force; it mythologized Fitzgerald’s vocal power as timeless and inescapable. Nothing was immune. A 1987 Jet magazine news item mentioned the Memorex spots as it reported that firefighters had rushed to Fitzgerald’s Beverly Hills home after her singing triggered a fire alarm — all while she was recovering from open-heart surgery at age 69.

Now, many technologies later and decades after Fitzgerald’s 1996 death, these cassette commercials may feel like the distant past. But the question of how we relate to analog or digital voices has never left us: Memorex’s marriage of cassette technology and Fitzgerald’s musical presence resonates today in our relationship with AI voices like Siri and Alexa. Fitzgerald’s unique talent and character in these 1970s spots point to why her voice in particular endures as a hallmark of style, quality and invention. Only Ella Fitzgerald, in the living, singing flesh, could have become The Memorex Lady. She was an American original.