Residents Of Warm Springs Reservation Still Without Clean Water After 3 Months

Read On

BY EMILY CURETON / OPB

The Warm Springs Indian Reservation in Central Oregon has been without safe drinking water all summer. Some people don’t have running water at all. In May, a burst pipe led to a cascade of infrastructure failures. That leaves around 4,000 people improvising for an essential human need.

“I’ll go back to being a teacher, hopefully, after this is done,” said Dorothea Thurby, a volunteer emergency manager whose days now revolve around a man-made disaster.

The preschool where she teaches shut down when the water system failed. Thurby was furloughed.

At an ad-hoc water distribution center on the reservation, she lifts about 1,000 pounds of water containers a day, organizes supplies and helps keep mobile showers clean. She said her main job, though, is being a leader, supervising youth workers as they work out of an old grade school building. It’s where she was once a student.

“I wish we could make something better out of this place, but right now we have to store all of our water in here,” Thurby said.

She surveyed bottles taking up one of the defunct classrooms. “See how the sunlight hits some of the gallons?” she said. “… We’ll cover those blinds, because when the sunlight hits the water too long, it creates algae.”

She said the window shades were open so she could see to take an inventory. The results made her anxious.

“We’re low … and so in my mind, I’m thinking, what if we don’t have enough?” she said. “I want to help serve the community, and say we run out. What are we going to do?”

The center runs on donations, and it might distribute 3,000 gallons of water a day, plus other supplies like bleach wipes, plastic plates, utensils and commodes, said Danny Martinez, emergency manager for the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs.

At first, donated supplies poured in from all over the Pacific Northwest.

“But they’re all hoping that it’s resolved today,” Martinez said. “And so when I call them back, they’re kind of puzzled by it. … ‘You mean you still don’t have water, Dan?’”

The list of problems is long. Firefighters can’t count on hydrants to work, Martinez said, and “the sprinkler system, the cooling systems, air-conditioning systems, the restrooms, the toilets, everything is affected by lack of water.”

Meanwhile, federal agencies have been slow to commit money toward long-term fixes in Warm Springs. At the same time, the Environmental Protection Agency has threatened to fine the tribe nearly $60,000 a day if it doesn’t make repairs by October.

Mobile sinks and showers set up on the Warm Springs Reservation, Aug. 2, 2019. CREDIT: Emily Cureton/OPB

The EPA order says “the system may present imminent and substantial endangerment” to human health, while “state and local authorities have not acted to protect the health of such persons.”

A spokesperson for the EPA said the tribes have not requested funding from its water infrastructure-related loans and that it would be unlikely to get such an application approved since those programs require systems to bill individual users for water. That idea has been shot down by Warm Springs tribal members before.

A spokesperson for the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, said in an email that the tribes have not asked for aid since the Warm Springs Tribal Council declared an emergency May 31.

In an unusual move, this summer the Oregon Legislature stepped in, earmarking $7.8 million in lottery bonds for water and sewer projects on the reservation. The amount is about half of what Rep. Daniel Bonham, R-The Dalles, said he first proposed adding to an omnibus bill.

“Although [Warm Springs is] a sovereign nation, they are also my constituents,” Bonham said.

“There are philosophical questions we can ask at some point, about what should the state’s role be, what is the federal government’s commitment in terms of treaties already signed. But right now we’ve got a community in need,” Bonham said. He added: “If everybody is responsible, then no one is responsible.”

Still, the state lottery bonds won’t pay out before 2021, according to the governor’s office.

Leaders from the Bureau of Indian Affairs declined to be interviewed and a spokesperson sent a written statement: “The trust relationship is shared by all federal agencies, not just the BIA. The specific level duties and appropriate responses that fall under the trust responsibility will be dependent on the factual circumstances and the treaty, statute, or regulation at issue,” according to the statement.

The BIA statement said the agency has provided over $400,000 in emergency funding for things like bottled water and portable bathrooms in Warm Springs.

The Indian Health Service, an agency within the federal Department of Health and Human Services with responsibility for serving Native populations, said in a statement it has been responding. IHS said it has sent engineers to the reservation six times since November and helped with funding applications, but those will take years to be ready to move into construction.

Nationally, IHS has found Native homes are nine times more likely to lack access to safe water than those in the general population.

According to Warm Springs Chief Operating Officer Alyssa Macy, repairs underway now “are considered temporary, and temporary is a couple of years … because we know this isn’t the permanent fix,” as reported by the tribally owned radio station KWSO in June.

Macy did not respond to requests for comment.

The boil water notice could be lifted by the end of the month, but that timeline has been extended before.

On a recent morning at the water distribution center, two teenage volunteers took a break from hauling water around in the warm weather to chase a yellow butterfly.

Fifteen-year-old Cajun-Rain Scott giggled as she tried to cup it in her hands.

“Butterflies keep coming around me,” she said. “… That’s good. … That means change.”

She said summer normally means “having fun with my friends and skateboarding. But I can’t do that now because I’m helping the community, and that’s more important than skateboarding, so I’d rather be doing this.”

Copyright 2019 Oregon Public Broadcasting. To see more, visit opb.org

Related Stories:

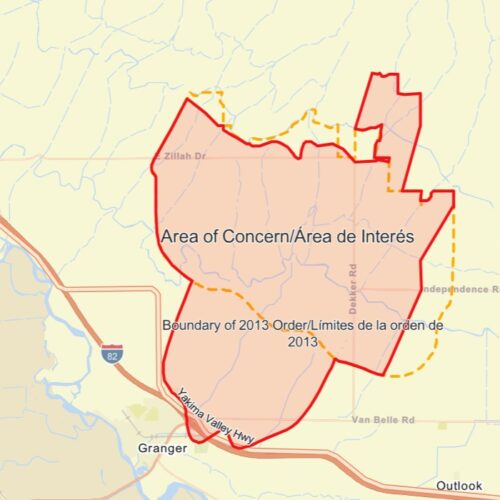

Federal judge orders Yakima County dairies to test wells, drinking water

A federal judge in Eastern Washington granted a preliminary injunction in a lawsuit that

involves over ten Yakima County dairy producers.

Elevated ‘forever chemicals’ found in Kennewick’s drinking water

The city of Kennewick has found “forever chemicals” in its drinking water. (Credit: Steve Johnson / Flickr Creative Commons) Listen (Runtime 0:53) Read The city of Kennewick has detected “forever

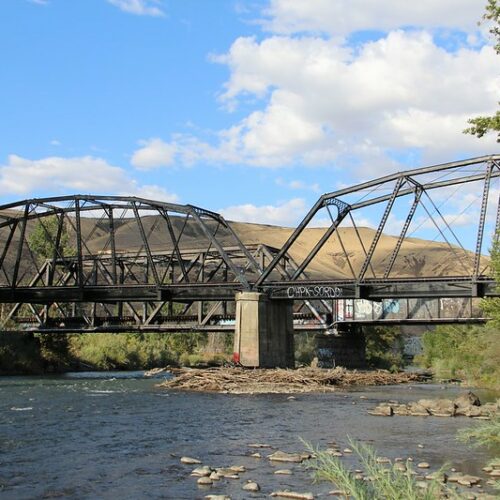

NW drinking water concerns could get worse as climate changes

The Naches River is the main source of drinking water for the City of Yakima. Credit: Cmh2315fl, Flickr Creative Commons.) Listen (Runtime 1:02) Read Thunderstorms high in the Cascades recently