Most Teachers Don’t Teach Climate Change; 4 In 5 Parents Wish They Did

GRAPHIC: ANGELA HSIEH/NPR

BY ANYHA KAMENETZ, NPR

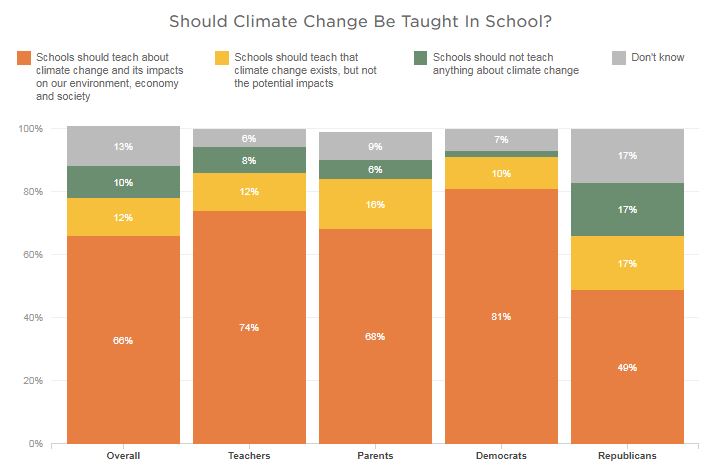

More than 80% of parents in the U.S. support the teaching of climate change. And that support crosses political divides, according to the results of an exclusive new NPR/Ipsos poll: Whether they have children or not, two-thirds of Republicans and 9 in 10 Democrats agree that the subject needs to be taught in school.

A separate poll of teachers found that they are even more supportive, in theory — 86% agree that climate change should be taught.

These polls are among the first to gauge public and teacher opinion on how climate change should be taught to the generation that in the coming years will face its intensifying consequences: children.

Source: NPR/Ipsos polls of 1,007 U.S. adults conducted March 21-22 and 505 teachers conducted March 21-29. The credibility interval for the overall sample is 3.5 percentage points; parents, 7.3 percentage points; and teachers, 5.0 percentage points. Totals may not add up to 100 percent because of rounding.

CREDIT: ALYSON HURT/NPR

And yet, as millions of students around the globe participate in Earth Day events on Monday, our poll also found a disconnect. Although most states have classroom standards that at least mention human-caused climate change, most teachers aren’t actually talking about climate change in their classrooms. And fewer than half of parents have discussed the issue with their children.

When it comes to one of the biggest global problems, the default message from older generations to younger ones is silence.

Parents And The General Public

Laine Fabijanic, a mother of three living in Glenwood Springs, Colo., says her part of the country is feeling the effects of climate change, from an unusually snowless winter last year to scary fires. She and her family recycle and eat organic; they are even installing solar panels on the house.

Still, she says she hasn’t talked about the big picture of climate change with her young daughters. “I don’t think we’ve talked much about it at all,” she said in an interview. “Probably because it hasn’t come up from them.”

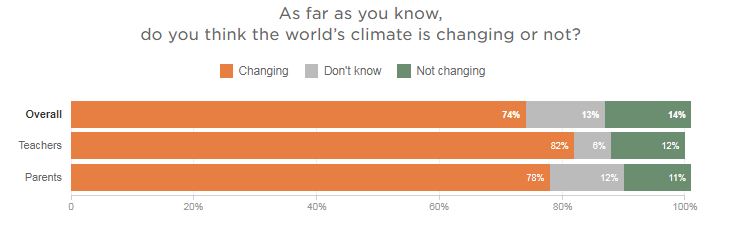

About 3 in 4 respondents in our nationally representative survey of 1,007 Americans agreed that the climate is changing. That figure is in line with previous results from Ipsos and other polls.

Source: NPR/Ipsos polls of 1,007 U.S. adults conducted March 21-22 and 505 teachers conducted March 21-29. The credibility interval for the overall sample is 3.5 percentage points; parents, 7.3 percentage points; and teachers, 5 percentage points. Totals may not add up to 100 percent because of rounding.

CREDIT: ALYSON HURT/NPR

Parents are even more likely than the general public to support teaching students thoroughly about climate change, including its effects on our environment, economy and society. Among parents with children under 18, 84% agree that it should be taught in schools.

A plurality of all parents support starting those lessons as early as elementary school. And though it may be a controversial subject, 65% of those who thought climate change should be taught didn’t think parental permission was necessary. Among Republicans, the corresponding figure was 57%.

However, parents like Fabijanic aren’t necessarily holding these conversations themselves. Just 45% of parents said they had ever discussed the topic with their own children.

Teachers Support Teaching Climate Change More In Theory Than In Practice

If they don’t hear about it at home, will kids learn about climate change in school? To answer this question, NPR/Ipsos also completed a nationally representative survey of around 500 teachers. These educators were even more likely than the general public to believe in climate change and to support teaching climate change.

In fact, 86% of teachers believe climate change should be taught in schools. In theory.

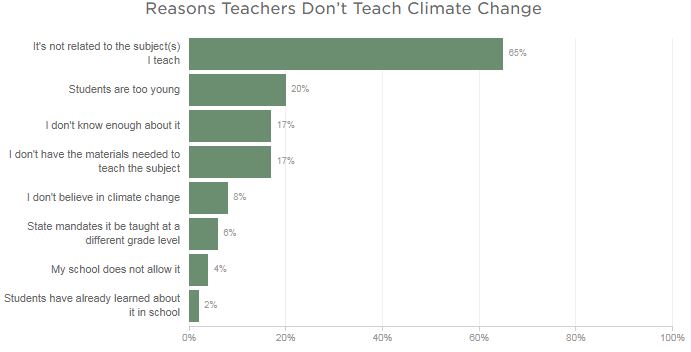

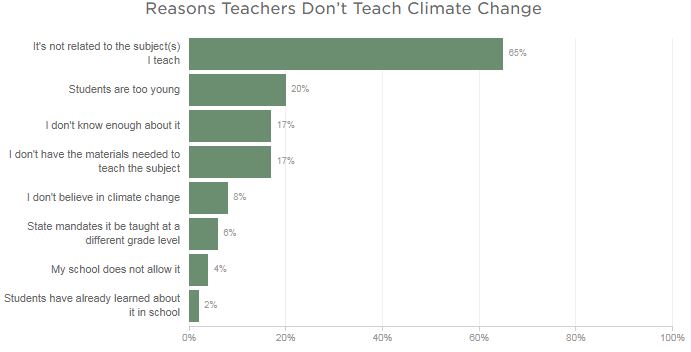

But in practice, it’s more complicated. More than half — 55% — of teachers we surveyed said they do not cover climate change in their own classrooms or even talk to their students about it.

The most common reason given? Nearly two-thirds (65%) said it’s outside their subject area.

Source: NPR/Ipsos polls of 505 teachers conducted March 21-29. The credibility interval for the overall sample is 5 percentage points. This question was asked of the 55% of teachers who said that they do not teach climate change. Respondents could select up to three answers. “Other” and “Don’t know” responses not shown.

CREDIT: ALYSON HURT/NPR

Let’s not forget that teachers are busy, and often underresourced and overworked. When asked to rank the importance of climate change, it fell to near the bottom of a list of priorities for expanding the curriculum, behind science and math, basic literacy and financial education.

Parents Seen As Obstacles To Teaching Climate

But there are other factors at work, too, in the decision of whether to cover climate change.

For example, almost a third of all teachers say that when it comes to teaching climate change, they worry about parent complaints.

Source: NPR/Ipsos polls of 505 teachers conducted March 21-29. The credibility interval for the overall sample is 5 percentage points.

CREDIT: ALYSON HURT/NPR

In our poll, teachers who do not teach the subject were allowed to choose more than one reason. They named many obstacles.

- 17% say they don’t have the materials.

- 17% also say they don’t know enough about the subject to teach it.

- 4% say their school does not allow the subject to be taught.

Moreover, there also seems to be a divide in terms of resources, attitudes and support between teachers who cover climate change in their classrooms and those who don’t.

Mallory Newall of Ipsos said for some teachers, maintaining that it’s not their job to teach climate change “may just be a way to rationalize why they’re not talking about it.”

That’s because teachers who do talk about climate change are also more likely to say:

- There should be state laws that require teaching it (70% versus 38% of teachers who don’t talk about climate change).

- They have the resources they need to answer students’ questions about climate change (77% versus 32%).

- Their students have brought up climate change in the classroom this year (78% versus 14%).

- Their school encourages them to discuss climate change (64% versus 18%).

In our NPR Ed newsletter, we did a callout to teachers to find out more about how they teach climate change. Some teachers we heard from mentioned the divisiveness of the issue and the difficulty in dealing with students whose parents are deniers of climate change.

“There’s so much political jargon around climate change that I would either have to dismiss their concerns that they bring up or burn a lot of time talking about something that is outside my content area,” said Jack Erickson, a science teacher at Cienega High School in Vail, Ariz., in response to our callout.

Some Teachers Get Creative In Teaching Climate Change

On the other hand, about 42% of teachers in our survey said they are indeed finding ways to address climate change in the classroom.

In our callout, we heard from far more than just science teachers. Preschool, English, public speaking, Spanish, statistics, social studies teachers — even home economics teachers and librarians — all are finding ways to approach the topic.

For example, Rebecca Meyer is an eighth-grade English language arts teacher at Bronx Park Middle School in New York City. Meyer’s students researched water scarcity and then read a “cli-fi” (or climate-fiction) novel by Mindy McGinnis called Not a Drop to Drink.

“The main character, Lynn, lives in a version of the U.S. where physical water scarcity is the norm. As we read the novel, kids made connections between what is happening today and the novel,” she told NPR. “They were very engaged; they loved it. They learned so much they didn’t know.”

Debra Freeman teaches family and consumer science — what used to be called home economics — at McDougle Middle School in Chapel Hill, N.C. Her curriculum includes healthy food choices.

“Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health is directly connecting the overconsumption of animal products to our global warming dilemma,” she says. “We also touch on the role of food waste (a huge problem in the U.S.) and its effect on climate change. Students in middle school are at a pivotal age for developing a multifaceted lens for thinking, evaluating and problem-solving. I place great hope in them!”

Erin Royer’s mixed-age classroom at Steele Elementary School in Denver comprises fourth- and fifth-graders. Does she cover climate change in elementary school? “Hell yes!” she says. “If you teach from a problem-based learning style, students will repeatedly arrive at climate change as the cause and effect of many problems/issues in their world.”

Whether the topic is animals, energy, or hurricanes and wildfires, “When they read information, through their research, put out by reliable scientists, they arrive at climate change again and again.”

And Lily Sage teaches “really little people” at the Schuylkill Center for Environmental Education’s nature-focused preschool in Philadelphia. “It’s a little above their heads, but we talk about Earth changes and ways we can avoid the ones that are causing mass extinctions. Because dinosaurs are accessible to them, that is often the framing for that conversation.”

State School Policies Mostly Include Climate Change

Since 2013, 19 states and the District of Columbia have adopted the Next Generation Science Standards, created by a consortium of states and science authorities to strengthen the teaching of science. The standards instruct teachers to cover the facts of human-caused climate change beginning in middle school. According to an analysis done for NPR Ed by Glenn Branch, deputy director of the National Center for Science Education, 36 states in total currently recognize human-caused climate change somewhere in their state standards. But, he says, “the fact that human-caused climate change is included in a state’s science standards doesn’t mean that teachers in that state do teach it,” and vice versa.

Moreover, this year alone, there have been numerous bills and resolutions introduced in statehouses that would restrict the teaching of climate change.

In Connecticut, a recent bill would have cut climate change materials from the state’s standards. An Iowa bill would have directly repealed the state’s use of Next Generation Science Standards.

Others — including in Arizona, Maine, South Dakota and Virginia — would prohibit the teaching of any issue included in a state political party platform, on the grounds of anti-indoctrination. Florida’s bill prescribes “balanced” teaching for “controversial” science subjects.

While most of these bills were tabled or failed to pass (Florida’s is still live), Branch sees them as part of a concerted and continuing effort to block the teaching of mainstream science. For example, some of these bills resemble model legislation created years ago by the American Legislative Exchange Council, a group that brings businesses together with lawmakers to write bills that are often industry-friendly.

Students Are Feeling The Effects

As the political debate continues, more and more students don’t have to wait to learn about climate impacts in the classroom. That’s because they are experiencing them in their daily lives.

NPR Ed found in an analysis that in just one semester, the fall of 2017, for example, 9 million U.S. students across nine states and Puerto Rico missed some amount of school owing to natural disasters — which scientists say are becoming more frequent and severe because of climate change.

The Schools for Climate Action Summit in Washington, D.C., in March, was instigated by students in Northern California whose communities were ravaged by wildfires. They also brought together students affected by Hurricane Harvey in Houston and by agricultural droughts on tribal lands in New Mexico to lobby at the Capitol.

Celeste Palmer, a high school junior, came to the summit with scraps of burned paper that had drifted into her Santa Rosa, Calif., neighborhood from the Tubbs Fire in 2017. She calls climate change “a generational justice issue for my generation in particular … because it’s affecting us now.”