Paint-By-Numbers Maestro Dan Robbins Dies At 93

PHOTO: Paint By Numbers Collection/NMAH Archives Center

LISTEN

BY ELIZABETH BLAIR

Critics were aghast, but hobbyists couldn’t get enough of it: In the mid-1950s, paint-by-numbers kits were all the rage. Dan Robbins, the artist who helped invent those kits, died at a hospice on Monday in Sylvania, Ohio, at age 93.

After World War II, Robbins was working as a package designer for Palmer Paint Company in Detroit. Company owner Max Klein was looking for a product that would appeal to adult hobbyists, and Robbins remembered something he learned in high school: Leonardo da Vinci’s numbering system.

“I remembered hearing about how Leonardo da Vinci would challenge his own students or apprentices with creative assignments.” Robbins wrote in his autobiography. “He would hand out numbered patterns indicating where certain colors should be used in specific projects such as underpainting, preliminary background colors or some lesser works that did not require his immediate attention.”

Palmer began to produce paint-by-number kits under the name Craft Master. At first, Robbins created his own compositions for the kits. “Dad was strong in seascapes so he did a lot of those at first,” says his son, Larry Robbins. “Then he’d go back, lay a clear plastic sheet over the original and assign numbers to the colors he’d laid down.” Beginner kits might have only 20 colors, intermediate kits as many as 30 or 40. Leisure time being at an all-time high after the war, some 20 million paint-by-number kits sold in 1955 alone.

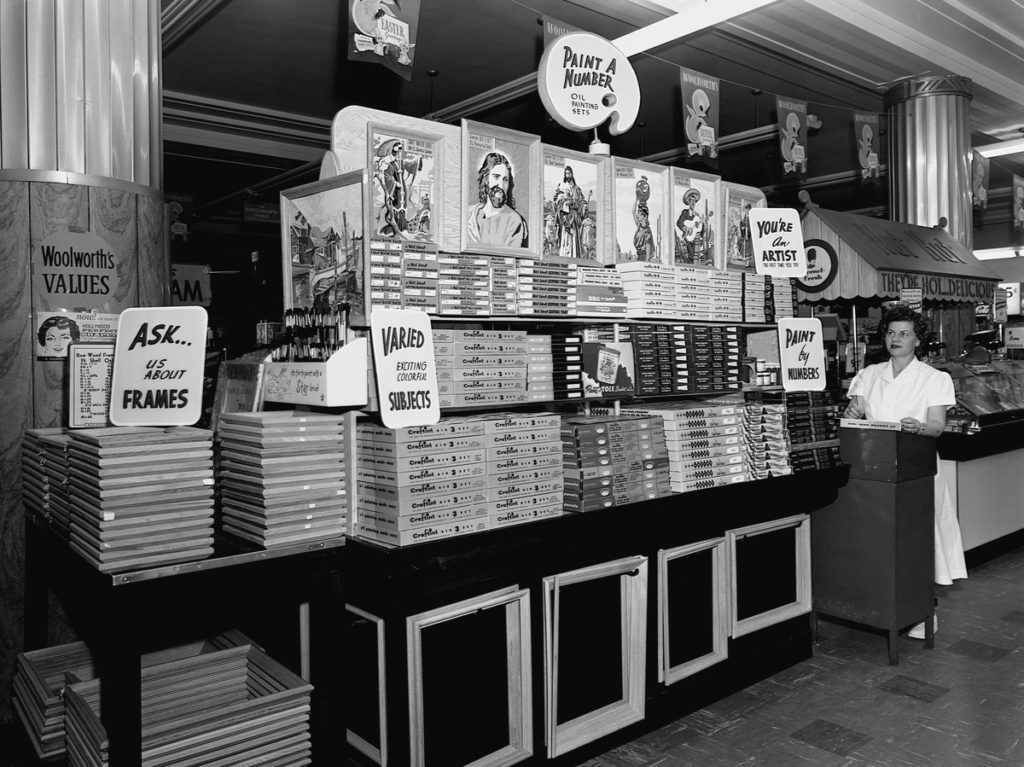

A saleswoman at Woolworth’s Five and Dime store sells paint-by-number kits — after World War II, people had more leisure time to paint, and the kits took off. CREDIT: Minnesota Historical Society/Corbis via Getty Images

In 2001, the Smithsonian Museum of American History explored the, er, style with the exhibition Paint by Number: Accounting for Taste in the 1950s, curated by William Lawrence Bird — now curator emeritus. What astonished Bird most was how Klein and Robbins figured out what people wanted to paint in order to keep up with the craze. “They had a customer base that was dependent on them to produce new subjects. So they’d read the mail,” People wanted pets, he adds — kittens, puppies and horses. The Last Supper was a particularly big hit. “And some people, when they would finish a painting, they would sign it.”

But Klein and Robbin’s Craft Master paint-by-numbers kits didn’t strike gold or even silver for their company, which faced bankruptcy at the height of their popularity. “Dan told me some 30 other companies entered the field, producing kits left and right,” says Bird. “So it became a craze that was beyond his power to control.”

Robbins kept on making his own art and working freelance for commercial clients. Curator emeritus Bird says one of those jobs was designing Happy Meals for McDonald’s.

As for the critics who dismissed paint-by-numbers as a ridiculous endeavor, Larry Robbins says his dad didn’t seem bothered by it.

“The big dilemma was ‘Is it art or not?’ I don’t think dad got caught up in defending it one way or another,” he says. Robbins believes his father took pride in giving people who might not otherwise have the opportunity “the experience of what it was like to paint,” regardless of their ability.

Bird agrees. He says Robbins “democratized access to the apparatus of art for people who would never have been exposed to them otherwise. He put brushes into the hands of people.” And, he adds, some of those people might have even been inspired to pick up their brushes and paint “without numbers.”