Idaho’s Proposition 2 Puts Medicaid Expansion To Voters After State Lawmakers Refused

Listen - Part 1

BY JAMES DAWSON / BSPR

Lewiston, Idaho, is a pulp mill town on the banks of the Snake River. Jet boats take visitors deep into Hells Canyon or schlep anglers to the perfect spot to catch a steelhead. The river also separates Lewiston from Clarkston, Wash. – both named in honor of the leaders of the Corps of Discovery.

Clarkston is where 54-year-old Marilena Delgado, who goes by Sugar, felt she had to move in 2014 – partially to get a fresh start after she broke up with her husband upriver in Orofino.

LISTEN – PART 2

But she also left to treat a rare condition called SMAS, which squishes parts of her intestines together, making it hard to eat.

“I had noticed the weight loss and the belly pain every time I eat, which I always call my ‘steak knife belly pain’. It’s just excruciating,” Delgado says.

The pain made her lose 50 pounds in a year, turning to protein shakes to try to help her keep on weight while working odd jobs.

“It’s just really taken a toll on my body, it really has,” she says. “I think if I could’ve gotten any answers sooner, I don’t think I’d be as frail as I feel half the time.”

She was able to enroll in Medicaid after moving across state lines to Clarkston – something she wouldn’t have been able to do had she stayed in Orofino.

But, if Idaho ever expands Medicaid eligibility, Delgado says she’d immediately move.

“I want to go back home. I want to go back to Orofino.”

Without Insurance

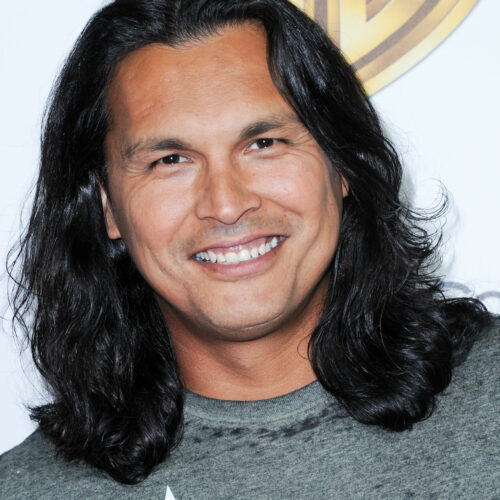

Hundreds of miles away in Idaho Falls, 48-year-old A’lana Marmel is one of the estimated 91,000 residents who could enroll in Medicaid if voters approve Proposition 2. She’s lived without insurance for much of her life.

A’lana Marmel from Idaho Falls is one of the estimated 91,000 people who would qualify for Medicaid coverage should voters approve Proposition 2.

JAMES DAWSON / BSPR

Her kids have insurance through Idaho’s Children’s Health Insurance Program, commonly known as CHIP. Although Marmel has a catastrophic insurance plan through her job, she can hardly meet her high deductible while working as a server in a local hotel.

“I don’t typically seek medical care for if I get sick and then we keep our fingers crossed,” she says.

If she would’ve gotten seriously sick while uninsured, the county or state taxpayers would likely have had to pick up her bills. Those costs typically add up to millions of dollars each year between the indigent fund and Catastrophic Health Care Fund.

But unlike Delgado, Marmel has no plans to move – even to get healthcare.

“I love Idaho. I live here because I love the mountains. I’ve been here for over 25 years now, so this is my home.”

Task Force Recommends Expansion

Back in 2012, Governor Butch Otter’s task force recommended lawmakers expand Medicaid coverage unanimously.

Former state Senator Dan Schmidt (D-Moscow) was in the group and remembers a consultant’s presentation early on.

“He kind of looks at us and says, ‘You know, I’ve done this for a lot of states, but this probably makes the most sense for you guys – Idaho,’” Schmidt says.

But the proposal went nowhere.

Despite projections showing the state would save $290 million over 10 years, many conservatives didn’t want to be more dependent on the federal government, or be seen as endorsing the Affordable Care Act.

“I think [Republicans] spent their energy on the state-based exchange and the fight was very bitter.”

In 2015, Schmidt tried to push an expansion bill through committee. When that failed, he tried to use a procedural move on the Senate floor to try to prevent his bill from being locked in a desk drawer, but many Republicans led by former Senate Majority Leader Bart Davis (R-Idaho Falls) quickly blocked it.

“With time, rather than trying to muscle legislation through, I have confidence that legislators will have an increased understanding of what’s the right approach, what’s the best approach, for Idaho going forward,” Davis said.

Some Republicans did want to fix the system, including state Rep. John Vander Woude (R-Nampa).

“The difficulty was is there was a bunch of them dead set, absolutely against it and some of them dead set in favor of it and to reach a consensus within the legislature is not as easy as you’d think,” Vander Woude said at a recent panel discussion on Proposition 2.

He opposes Medicaid expansion. He’d rather avoid the state paying for a catastrophic event and helping someone get preventive care instead.

But despite having six years to come up with a fix, lawmakers have punted every time.

Traveling Through The State

After years of inaction by the Idaho legislature on the state’s healthcare gap, three people traveled throughout the state on a hunch that residents were just as fed up as they were.

That hunch turned into a full-blown campaign to expand Medicaid. It’s also drawn in those who have felt forgotten by the political machine, including Amy Pratt. After 48 years, Pratt decided it was her turn to get involved.

Amy Pratt personally collected more than 1,000 signatures to help get Proposition 2 on the ballot. It’s the first time she’s been politically active and she has no plans of stopping.

CREDIT: JAMES DAWSON / BSPR

She set out to tell her neighbors in Idaho Falls why she thinks Idaho should expand Medicaid eligibility for up to 91,000 residents.

“I knocked on doors from January 6 until May 1, every door that I could possibly find. I didn’t get paid for it, I have a full-time job,” Pratt says. “I did this for the people that I love, I did this for the people that I care about, I did this for people I don’t even know.”

And that’s where we found her one afternoon, near Idaho Falls High School. She and about a dozen others had gathered in a nearby church basement to canvas nearby neighborhoods.

Not so long ago, Pratt says she wouldn’t have walked so many miles during the biting eastern Idaho winter. But she felt disenfranchised when, in 2002, state lawmakers repealed a popular ballot initiative that imposed term limits on elected officials.

“I felt unheard and uncared for. Maybe term limits was the wrong thing, but for them to overturn it and say that we were wrong was wrong. It was absolutely wrong,” Pratt says.

So here she is, with a clipboard in one hand and fliers in the other, knocking on more doors than she was assigned – reaching out to grab on to her own little piece of democracy. Pratt was one of the few volunteers who personally gathered more than 1,000 signatures to put Proposition 2 on the ballot.

She was inspired by Luke Mayville, a co-founder of Reclaim Idaho, the group leading this charge. She’s not alone.

Several other volunteers who spoke with Boise State Public Radio say this has been the first time they’ve volunteered for a campaign, whether it’s knocking on doors, calling potential voters or staffing a both at the local county fair. Many began paying attention to politics after the 2016 election, helping form liberal groups in traditionally conservative places across Idaho. Though some came from across the political spectrum.

Moment Of Inspiration

Mayville’s moment of inspiration came last Fall.

“The big breakthrough was when the state of Maine came along and proposed a ballot initiative to expand Medicaid. Because we stepped back and thought, whoa, they’re gonna win,” Mayville says.

And they did. Maine voters passed the measure by a near 20-point margin.

Emily Strizich and her husband Garrett are the other co-founders of Reclaim Idaho. It began as a movement to pass a supplemental school levy in Sandpoint – where Mayville and Garrett Strizich grew up.

Garrett and Emily Strizich, right, co-founders of Reclaim Idaho, canvas the recent University of Idaho homecoming tailgate to drum up votes for Proposition 2. They even bring their three-month-old daughter, Simone, with them.

CREDIT: JAMES DAWSON / BSPR

But after they won that fight, they started wondering what else they could do.

“Garrett came home and was just like, ‘Hey, I think we should paint our camper green and drive it around the state this summer.’ I’ll be honest that I thought they were insane,” Strizich says.

The trio eventually chose to see if there was any appetite in Idaho to expand Medicaid. Emily

Strizich wasn’t sure it would work.

“Here I was, not totally sold on the idea, and one of the first doors I knock on is this woman who is deciding between treating these [complications from cancer] that are going to kill her or making her family homeless. And she’s really grappling with this idea: Is my life worth saving?”

But after hearing more and more stories like that, she decided, yes, voters would want to expand Medicaid eligibility to Idaho’s working poor.

‘Antidote For Hopelessness’

Mayville Strizich calls talking to voters her “antidote for hopelessness.”

She worked through the campaign while pregnant and now brings the couple’s three-month-old daughter, Simone, to canvas at events like the University of Idaho homecoming tailgate.

The responses were nearly all positive. The campaign got a similar reaction the next day in more conservative Lewiston, about an hour’s drive south of Moscow.

Reclaim Idaho has cast itself as a grassroots, door-to-door movement, though some disagree.

Fred Birnbaum is the vice president of the Idaho Freedom Foundation. He says outside money – more than half a million dollars – was spent by a progressive group called the Fairness Project, which hired paid signature gatherers.

“I think you can say unequivocally, without the money from the Fairness Project based in D.C., this would not be a ballot initiative in Idaho. They put it over the top,” Birnbaum says.

Staffers at Reclaim Idaho have acknowledged this help was critical. Even though volunteers took in nearly all the signatures needed to get the measure on the ballot, there was a crucial time in March when they needed to reach a specific threshold required by Idaho law.

Grassroots Effort

Still, Jaclyn Kettler, a political science professor at Boise State University, says it’s fair to call this a grassroots effort.

“Canvassing, the door-to-door knocking matters – personal contact really matters for getting a voter to turnout or a citizen to turn out to vote,” Kettler says.

Jonathan Carkin, field director for Idahoans for Healthcare, trains a group of about a dozen volunteer door knockers in the Lewiston Orchards in October.

CREDIT JAMES DAWSON / BSPR

If Proposition 2 passes, lawmakers can add a variety of restrictions to it. They also need to pay for Idaho’s share of the program, which is 10 percent of any new costs from those who fall in the expansion population in 2020. Medicaid expansion is held up in Maine, for example, because the governor has refused to fund it.

Regardless of how it turns out at the polls, leaders within Reclaim Idaho intend to continue advocating for issues the state legislature has avoided. Their next campaign might involve universal pre-k education.

Building off of efforts like these can mean the difference between a one-and-done organization and one with staying power.

For Amy Pratt, at least, she sees a clear path ahead, even if Idaho doesn’t expand Medicaid.

“I’m not going to stop. Prop 2 won’t fail, but in the future, I’m going to be active.”

James Dawson on Twitter: @RadioDawson

Copyright 2018 Boise State Public Radio

Related Stories:

Think Your Health Care Costs Are Covered? Beware The ‘Junk’ Insurance Plan

Whether you’re looking for coverage online or through a broker, be sure to note the difference between a comprehensive health plan and a “junk” plan with limited benefits and coverage restrictions.

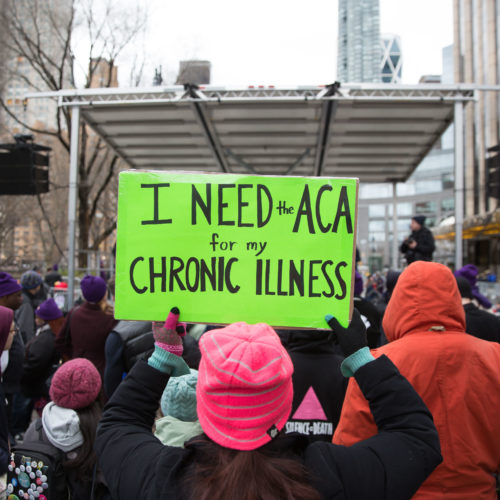

Affordable Care Act Again Goes Before Supreme Court, Now With Amy Coney Barrett On Bench

The Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare, is back before the Supreme Court, with opponents challenging it for a third time. The first attempts to derail the law failed in the high court by votes of 5-to-4 and 6-to-3. But the makeup of the court is very different now, with three justices appointed by President Trump – among them new Justice Amy Coney Barrett.

How Tea Party Budget Battles Left The National Emergency Medical Stockpile Unprepared

Dire shortages of vital medical equipment in the Strategic National Stockpile that are now hampering the coronavirus response trace back to the budget wars of the Obama years, when congressional Republicans elected on the Tea Party wave forced the White House to accept sweeping cuts to federal spending.