Saving bighorns for a collective future

watch

Listen

(Runtime 3:57)

Read

It’s about 8 a.m. on a bitingly cold December morning on the Idaho side of Hells Canyon. Wildlife biologists are pulling medical gear from large plastic boxes near the banks of the Snake River when the sound of an approaching helicopter fills the valley.

A moment later, it swings into view from between a gorge. It’s bright red and towing a rope with two blindfolded bighorn sheep, held secure in neon orange harnesses.

The helicopter sinks toward grassy clearing and gently lowers the animals onto the ground. The rope drops, and the helicopter is off again, and volunteers descend on the animals, toting them away to be weighed, tested for disease and collared.

A helicopter lowers wild sheep at a drop site in Hells Canyon where wildlife biologists assess their weight and body condition, test for disease and attach ear tags and radio collars. (Credit: Annie Warren / NWPB)

It’s an odd sight. To some, it might seem at odds with the picturesque imagery of the wild animals so iconic of the mountain West.

The reason for the bighorns’ capture, however, is an important one: to rehabilitate a fragile population that once roamed the region, by some estimates, in the tens of thousands.

Frances Cassirer is a wildlife biologist with Idaho Fish and Game. She’s been working with bighorn sheep in the Hells Canyon Initiative for over 20 years. It’s a program that brings together a disparate group of people for one purpose: to manage and protect the health of the Hells Canyon bighorns, and eventually, restore those populations.

Other volunteers for the project include sportsmen with the Wild Sheep Foundation, wildlife and land management agency representatives from Washington and Oregon, biologists from Washington State University, members of the Nez Perce Tribe and Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation (CTUIR) and others.

A bighorn ram makes its way into the hills after being radio collared and tested for disease. Wild sheep grow large in this region, says Frances Cassirer, of Idaho Fish and Game, due to a mild climate, abundant grasslands and low numbers of sheep overall. “We’re proud of our sheep,” she says. (Credit: Annie Warren / NWPB)

Bighorn sheep, Cassirer said, seem to have something special that brings people together. She muses that maybe it’s the sheep’s social personalities, or their athleticism, or their bravery. Cassirer can’t keep the smile off her face when she starts talking about the bighorns.

“When I say other people, maybe I mean myself,” she laughs. “They just go on these steep rocks, and you could go around, you know? So, I love that. I also love (that) they’re social, they’re just very inquisitive and they’re very interactive.”

The bighorn sheep’s relationship to Hells Canyon is a long and storied one. Bighorns, or “tin’úun” in the Nez Perce language, were the primary food source for Nez Perce and Cayuse people for generations and play an essential cultural and spiritual role for the tribes who relied on them to subsist since ancient times.

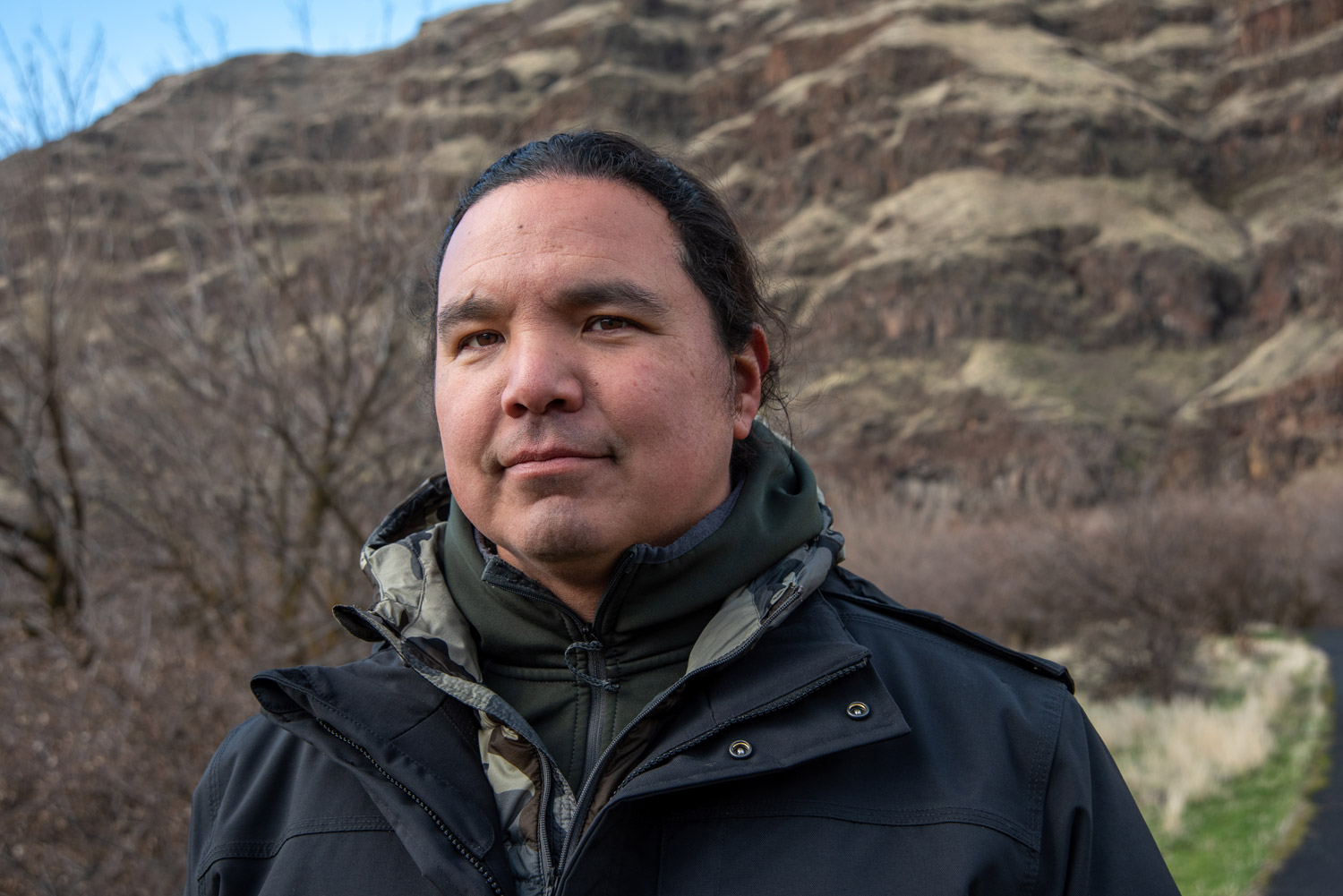

Andrew Wildbill, Cayuse, is the Wildlife Program manager for the CTUIR and took part in the sheep capture. His family lived near the Snake River for generations.

“My grandma’s grandma lived on the Snake River and in a hut house — in an earthen house. That’s where she was raised before our reservation was created, and the people who lived along the Snake relied heavily on mountain sheep,” he said.

Petroglyphs along the banks of the Snake River are estimated to be at least 2,000 years old and possibly date from as early as 4,500 years ago, and depict, among other things, bighorn sheep.

Josiah Pinkham Blackeagle holds a bighorn sheep horn on Thursday, Dec. 12 in Lapwai, Idaho. (Credit: Rachel Sun / NWPB)

James Holt works at the Nez Perce Tribe’s Department of Natural Resources. His tribe’s relationship with the bighorns date back even further, Holt said.

The oldest known settlement in North America, dated at roughly 16,000 years ago, is the Nez Perce village known as Nipéhe, or Coopers Ferry. Bighorn sheep, Holt said, were the primary food source for his ancestors, even before salmon.

“Today we call ourselves the salmon people. Many bands of Nez Perce do,” he said. “Before that, it was the bighorn sheep who were the main source of subsistence for us.”

Wild sheep are among the figures depicted at Buffalo Eddy, a National Nez Perce Historical Park site featuring petroglyphs and pictographs in Hells Canyon. The images possibly date from as early as 4,500 years ago. (Credit: Annie Warren / NWPB)

But starting in the late 1800s, bighorn sheep became threatened by unregulated hunting by the American public and the introduction of domestic sheep and goats that brought new diseases to wild populations.

Those stressors collapsed most bighorn populations across the United States, including those in Hells Canyon, in the early 1900s.

Wildlife biologists began reintroducing bighorns to Hells Canyon in the 1970s. But since then, the population has battled periodic die-off events fueled by mycoplasma ovipneumoniae, or M.ovi.

The bacteria causes respiratory disease in wild sheep and goats. Today, domestic sheep grazing is prohibited in the Hells Canyon National recreation area to protect the bighorns.

Once introduced by domestic sheep, M.ovi can also be spread by other among other wild bighorn populations, which is believed to be the case in the most recent die-off said Hollie Miyasaki, the statewide sheep manager for Idaho Fish and Game.

Eric Kash Kash, Nez Perce Tribe Wildlife Division director, left, participates in the sheep capture. His people have historically significant ties to the animals, he says, including using the skins for traditional clothing and making bows out of rams’ horns. (Credit: Annie Warren / NWPB)

During the bighorn capture, a team of helicopter-riding sheep catchers, known as “muggers,” use nets to capture the bighorns, then blindfold the animals and constrain their legs with hobbles.

When the sheep arrive on-site, wildlife biologists take nasal swabs and blood samples to test whether the bighorns are currently infected with M.ovi, and whether they have antibodies for the bacteria, which would indicate a past infection. The biologists also weigh the animals and use an ultrasound to check fat stores.

Some sheep, Miyasaki said, can become chronic carriers of the bacteria, consistently re-infecting the other bighorns.

Wildlife biologists assess a bighorn ewe for disease by taking nasal swabs and blood samples. The animal is fitted with a radio collar. A blindfold and hobbles help keep animals calm during the process. (Credit: Annie Warren / NWPB)

Lambs are particularly susceptible to M.ovi. Biologists suspect continued infections are the reason why, as the morning turns to afternoon, the muggers aren’t finding many lambs.

This early, Miyasaki said, it’s unclear if infected sheep are still in the process of clearing the bacteria.

“If they test positive twice, we’d consider them chronically infected and not likely to clear it,” she said. “They are the ones that keep reinfecting everybody and infecting the lambs.”

As of mid December, only one of the 46 sheep tested with confirmed results came back positive for an M.ovi infection.

Recently, the tribes have become more involved in the Hells Canyon Initiative as more Native conservationists step up to offer their expertise, perspective and cultural wisdom.

Even when Indigenous perspectives don’t immediately change a given practice, Cassirer said, it’s brought a mindfulness and depth to her work she didn’t have before.

Frances Cassirer describes bighorns as expressive, curious, brave and very social animals that unite people of all backgrounds. (Credit: Annie Warren / NWPB)

Cassirer has worked to donate animal parts to the tribes as she can when a wild sheep death occurs. She feels more aware of the animal and its value, she said, both when it’s alive and when it dies.

“The European perspective is more sort of utilitarian or protection. The tribal perspective, from what I understand, it’s just more reciprocal, it’s a relationship,” she said. “ I’m not trying to say, like, everybody’s messed up if they don’t see it this way. But it’s a way of thinking about things that my education didn’t really cover.”

Josiah Pinkham Blackeagle is a Nez Perce tribal member, hunter and ethnographer.

Nez Perce stories, Blackeagle said, tell of four-legged creatures, including the bighorns, offering their bodies for peoples’ survival. He said those stories are essential to Nez Perce peoples’ understanding of the world, their role in it and approach to conservation.

“It establishes elder kinfolk and junior kinfolk. The elder kinfolk are the animals. They say, ‘We’re going to give to these people to help them to survive. We’re going to guide them,’” Blackeagle said. “Those junior kinfolks are Nez Perce people.”

The sacrifice by the animals that sustained Nez Perce people also leaves them a responsibility as the recipients of that gift, Blackeagle said: to steward those animals and ensure the ability of future generations to hunt bighorns.

For him, Blackeagle said, the preservation of Nez Perce cultural, spiritual and language practices are deeply intertwined with conservation.

“All of that out there, the place in which you typically find tin’úun, or bighorn sheep, that’s my pharmacy. That’s my church. That’s my classroom. That’s my laboratory. That’s my home. It’s my grocery store,” Blackeagle said. “But in the American psyche, those things are all parsed out into different locations and places. I can’t do that. In fact, it’s taboo of me to think of my landscape like that.”

In recent years, more conservationists have begun to take cues from Indigenous environmental stewardship practices.

Blackeagle puts it simply:

“It’s not that we’re better human beings,” he said. “It’s about, the Nez Perce people have been here for at least 16,000 years. And we found out a lot of different things that don’t work.”

In the Nez Perce language, the word tamáalwit is used to describe a divine principle, defined broadly as “natural law.” It describes a spiritual and reciprocal relationship between the world, including bighorn sheep, and the Native people who subsist on them.

For members of CTUIR, that principle, tamánwit in their dialect of the language, is understood to put a major emphasis on First Foods.

Wildbill, who works to ensure CTUIR tribal members have access to First Foods including bighorn sheep on and off reservation lands, said for him, access to those foods are an essential part of identity.

“When you’re born, you’re given a name that the land recognizes you by, and your community recognizes you by. And then during that first step and after your first breath, you’re given these foods. Basically, it starts there,” he said. “When your time comes and you pass, we celebrate that person’s life with food as well.”

Andrew Wildbill, Cayuse, is the wildlife program manager for the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation and a hunter and provider in his community. He works to ensure tribal members’ access to wild sheep, an important First Food. “Our food is our identity,” he says. (Credit: Annie Warren / NWPB)

Tamáalwit touches all areas of his life, Blackeagle said. His relationship with the bighorns is first and foremost spiritual. Being a hunter, he said, means facilitating spiritual movement.

“You have to do something to take its life so that that spiritual energy can transition into food for others,” Blackeagle said.

From a Nez Perce understanding, bighorns are spiritual beings — elder kinfolk — that take care of people, Blackeagle said.

“We’re responsible for ensuring that that spiritual network is in place for our young people, because our young people go out and they seek guidance and help, (and) the elders come forth,” he said. “That spiritual network that steps forth to take care of people are mountain sheep, they’re condors, they’re eels, they’re coho salmon.”

A shirt made of hide includes a beaded fold of skin near the neckline from the tail of the animal. That design showcases cultural identity and relationship with the animal, says Josiah Pinkham Blackeagle. (Credit: Rachel Sun / NWPB)

Shirts and dresses made with bighorn hides often will include a triangle of skin folded at the neckline from the tail of the animal, either left with hair or decorated with beadwork, in recognition of the creature the hide came from.

“That’s one aspect of material culture in displaying identity, but also it’s a way of demonstrating relationships,” Blackeagle said.

That relationship is so strong, Blackeagle said, that research has shown a connection between the loss of Indigenous language and a drop in biodiversity. The understanding of people, animals, places and how they relate to each other are built into the language itself.

“You look at something like a mountain sheep and you see everything that contributes to it being in the world. That’s the empowerment of Nez Perce language, is that you look at things just differently,” he said.

For Nez Perce people, Holt said, preserving wild animal populations and their environment is tantamount to preserving the people themselves.

“I’ve buried a lot of people, Nez Perces, all of them. They’re dying — we’re dying — at accelerated rates,” Holt said. “The issues that face the bighorn sheep with these sicknesses and diseases are affecting humans. We are the environment we live in. Bighorn sheep are showing us that. Salmon are showing us that.”

But promoting biodiversity and restoration isn’t just a job for the tribes, Blackeagle said.

Research has shown that on a broader scale, biodiversity is important for human health because of the role healthy ecosystems play in access to food, water, medicine and disease prevention.

Josiah Pinkham Blackeagle is a Nez Perce tribal member, hunter and ethnographer. He says the preservation of Nez Perce cultural, spiritual and language practices are deeply intertwined with conservation. (Credit: Rachel Sun / NWPB)

Blackeagle said he can’t offer an easy solution for non-Native people looking to reevaluate their relationship with the environment. He doesn’t want people to be “Indianists,” blindly copying whatever they see Native American people are doing.

But, Blackeagle said, he thinks part of the work in wildlife restoration includes building connections with Indigenous people, and working continually to invest in the future. Blackeagle resists framing conservation in terms of successes or failures.

“Success kind of implies this destination, or this point of finality, you know, the work’s done,” he said. “It’s never going to be done because we have to ensure, first and foremost, that the values are transgenerational.”

Holt hopes continued restoration efforts will eventually bring bighorn populations back to the thousands that once roamed Hells Canyon. Today, the bighorn sheep population there is estimated to be roughly 1,000 in the entire Hells Canyon, and roughly 150 living in the area scientists surveyed this month.

“Maybe it won’t happen in my lifetime, but maybe my children will be able to enjoy that,” he said. “They can maybe have a relationship and do things along with the bighorn sheep that I wasn’t able to do.”

In Holt’s role, he interacts with members of the public who aren’t tribal members. Restoring bighorn sheep, and other native populations, affects all people living within an environment, he said.

“That’s the sacredness of these things. They will catch everybody up and pull everybody in that tailwind,” Holt said. “We’re all connected in some way as neighbors, as people who live in these environments and on these rivers and in these mountains together.”

The setting sun illuminates hills on the Idaho side of Hells Canyon, across from Buffalo Eddy, a petroglyph site of the National Nez Perce Historical Park along the Snake River. The canyon is home to Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep, a culturally significant species for the Nimiipuu, or Nez Perce Tribe, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation and other Indigenous peoples since time immemorial. (Credit: Annie Warren / NWPB)

Want to hear more about how cultural stories shape Nez Perce understandings of their relationship with their environment?

Listen to Josiah Pinkham Blackeagle share a story about the relationship between wolves, ungulates and Nez Perce people.

(Runtime 6:46)