Pertussis on the rise in the Northwest

watch

Listen

(Runtime 0:56)

Read

Pertussis, or whooping cough, is on the rise throughout Washington state, Oregon and Idaho this year.

The Oregon Health Authority is reporting over 800 cases of pertussis in the state as of Wednesday. The agency expects Oregon will soon surpass its 2012 record of 910 cases.

Pertussis is a highly contagious bacterial infection. It poses the highest risk of severe infection or death for infants under one year old and people who are elderly or immunocompromised.

In Oregon, pertussis was reported in 23 counties, and at least one person, an older adult, has died. Lane County has the highest number with 249 cases, followed by Multnomah County with 180, Clackamas County with 109, Washington County with 67 and Deschutes County with 59.

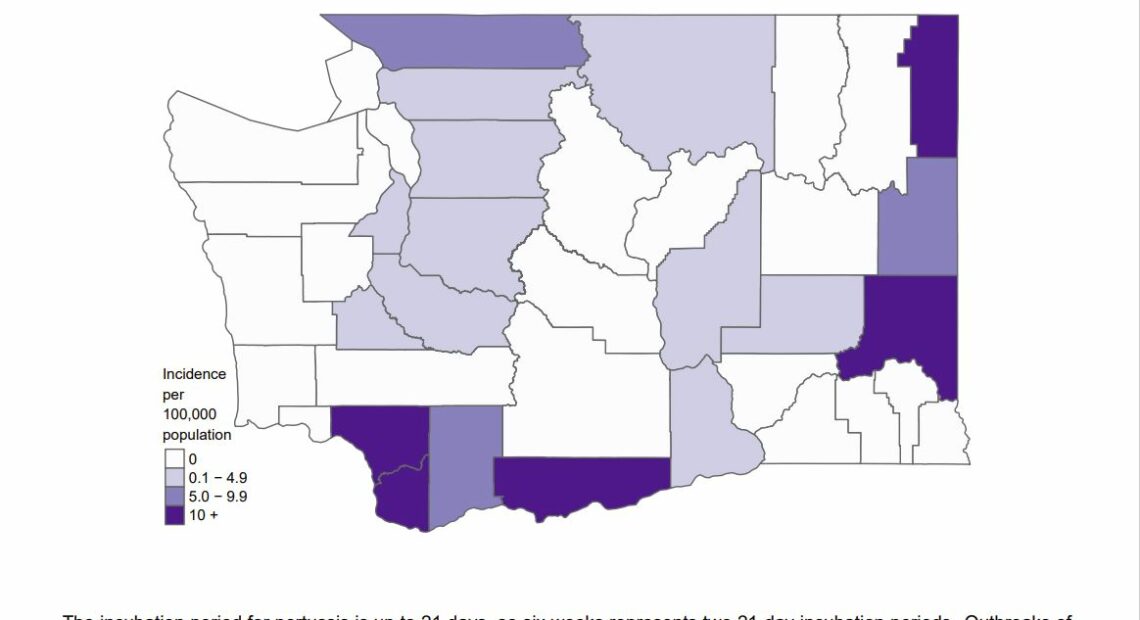

In Washington, the state reported a total of 1,193 cases so far in 2024, compared to 51 cases the same time last year.

Idaho has reported over 700 cases of pertussis this year, compared to 34 in 2023.

Pertussis has been reported in 31 counties in Washington, with Whitman County showing the highest rate per 100,000 followed by Clark, Douglas and Grant counties.

Whitman County Public Health director Chris Skidmore said in Pullman, most of the 63 total cases have remained within the student body at Washington State University.

“We have had a handful of cases that are outside of that student population, but they haven’t gone on to lead to further infection,” Skidmore said.

As of early November, 28 people in Washington had been hospitalized, including 12 infants under the age of one, according to the state’s health department.

In Idaho, nine people have been hospitalized for pertussis including four infants, one child aged between the ages of one and four years old, two teenagers and two adults over the age of 50.

Pertussis usually takes five to 10 days for symptoms to appear following exposure to the bacteria that causes it. Unlike adults, infants with pertussis may not cough as much or at all, but develop apnea, a life-threatening pause in breathing.

In its early stages, which may last one to two weeks, pertussis causes cold-like symptoms including a runny or stuffed-up nose, low-grade fever and occasional coughing. However, Skidmore said, testing for pertussis is available.

“I think everybody should, if they are noticing symptoms, be checking in with a primary care provider to get tested,” Skidmore said.

In its early stages, pertussis can be treated with antibiotics. Early testing and treatment can prevent more severe symptoms that last for weeks.

“After about two weeks, it usually becomes really aggressive, and at that point, it’s no longer treatable with antibiotics,” Skidmore said. “You’re kind of stuck suffering out of the rest of the illness.”

Later stages of pertussis can include severe coughing fits, a “whoop” sound caused by the person gasping for air between coughs, and vomiting and exhaustion after coughing fits. This stage typically lasts one to six weeks, but may extend as long as 10 weeks.

After this, a person with pertussis will eventually start coughing less as they recover over the course of two to three weeks.

Early treatment also helps prevent the spread of pertussis. People diagnosed with pertussis are advised to stay home until they have been treated with antibiotics for five days, or until 21 days have passed since symptoms began.

The most effective prevention for pertussis is vaccination. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends a five-series DTaP vaccination at the ages of two months, four months, six months, 15 through 18 months, and 4 through 6 years.

Adolescent children and adults who never received a Tdap booster as an adolescent may receive the Tdap vaccination.

Though no additional Tdap vaccines are required for adults, adults do need boosters every 10 years to maintain protection against tetanus and diphtheria. Health care providers may administer either Td or Tdap for such boosters.

Tdap vaccines are specifically recommended for pregnant people and those who are likely to be exposed to an infant under one year old, such as people sharing a household with a baby or child care workers.

“The best tool that we have is to vaccinate mom during pregnancy, because mom will make antibodies against pertussis, and then push them across the placenta to baby,” said Dr. Paul Cieslak, medical director for communicable diseases and immunizations at the Oregon Health Authority’s Public Health Division.

Vaccinating pregnant people has been shown to be 78% to 91% effective at lowering the risk of pertussis in babies younger than two months old.

Cieslak noted one case of an infant who was hospitalized for months in 2012 due to pertussis.

“On a respirator, a million and a half dollars in hospital charges,” he said. “This is the kind of thing we’re trying to prevent.”

With the exception of 2024, Oregon pertussis deaths have been limited to infants — five have occurred since 2003.

Pertussis vaccines typically offer high levels of protection within the first two years after getting the vaccine, and wane over time. In general, DTaP vaccines are 80% to 90% effective, according to Whitman County Public Health.

Though vaccines are not 100% effective in preventing pertussis, vaccinated people who do get sick usually experience milder symptoms, according to the American Lung Association.

In addition to vaccinations, good respiratory virus hygiene can help prevent pertussis. This includes washing hands frequently for at least 20 seconds with soap and water, using hand sanitizer if soap and water are unavailable, and covering coughs and sneezes.

If someone is experiencing respiratory symptoms but needs to leave their home, wearing a mask can help prevent the spread of pertussis and other respiratory illnesses.