Oregon Attorneys Argue State’s Juvenile Sentencing Laws Are Unconstitutional

Listen

On March 26, 2001, Barbara Thomas was killed by her teenage son and four of his friends near Redmond, Oregon.

Police say she was struck in the head with a glass bottle, repeatedly and then shot. The teens became known as the “Redmond Five.” After killing Thomas the teens stole her Honda coupe and drove for Canada. They were arrested when they tried to cross the border.

One of the teens was Justin Link. He was found guilty of aggravated murder and sentenced to a mandatory minimum of 30 years in prison, with the possibility of applying for parole after that. He is appealing that sentence to the Oregon Court of Appeals.

Attorneys and lawmakers in Oregon say the state is violating the U.S. Constitution because of laws that require juveniles convicted of murder to be sentenced to what amounts to mandatory life imprisonment. Link’s case going before the state’s court of appeals Friday could push lawmakers to take action.

“(He) was 17 years old when he and four friends committed aggravated murder,” says Marc Brown, Link’s attorney and Oregon’s chief deputy public defender for appeals. “Justin did not actually pull the trigger.”

“We’re saying … this is unconstitutional as applied to all juveniles,” says Brown.

In 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in a case called Miller v. Alabama. The nation’s high court ruled it was a violation of the 8th Amendment to sentence a juvenile to the life without the possibility of parole if that’s the only sentence a judge or jury can impose. In other words, there needs to be options.

On paper, Oregon has two options for sentencing juveniles convicted of aggravated murder.

Life without the possibility of parole; or a minimum sentence of 30 years in prison after which your sentence may be converted to one with a possibility of parole. But the possibility of parole isn’t a given. First, Link has to prove he will be rehabilitated, then the sentence is converted, and only then he can apply for parole.

Attorney Marc Brown argues that the two sentences are effectively the same. He says that parole after 30 years is speculative.

“At the time of sentencing they’re both life without the possibility of parole,” he says.

Former Deschutes County District Attorney Mike Dugan says Brown’s argument doesn’t make any sense. His office prosecuted Link.

“It’s an opportunity for the offender to prove rehabilitation,” Dugan says. “So, there’s a choice there. And it’s going to be part of the choice of the offender.”

Currently, 23 juveniles are serving life sentences for aggravated murder, according to the Oregon Department of Corrections.

The case playing out in Oregon falls in line with efforts across the country to make sure juvenile sentencing laws are consistent with the Supreme Court’s interpretation.

The Supreme Court has found when it comes to sentencing, juveniles must be treated differently because of their level of brain development, says Heather Renwick, legal director at the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth.

“Because our adolescent brains are hypersensitive to immediate surroundings and not as capable as thinking several steps ahead as adults are,” Renwick says. “So the Court looked at all of those things and said because kids are fundamentally different that adults, we have to understand their culpability differently.”

Renwick says 20 states across the country now ban life without the possibility of parole for juveniles.

“Oregon is an outlier or sort of falling behind the national movement because it hasn’t yet taken legislative action,” she says.

A bipartisan group of state lawmakers in Oregon is looking to change that. Legislators are also taking a broad look at voter approved mandatory sentencing laws — known as Measure 11 — that affect juveniles. The laws have been in place for more than 20 years.

“I would argue that our system is currently unconstitutional under Miller,” says Jennifer Williamson, the democratic majority leader in the Oregon House. She is referring to the 2012 Supreme Court case. “We have to change that in order to be compliant. And because I think it’s the right thing to do.”

For Dugan, the former Deschutes County DA, crime victims are a crucial part of that conversation.

“The system needs to understand the impact that the crime has on victims,” he says. “It’s important that they have their voice be heard.”

Critics say Measure 11 and the laws surrounding juvenile sentencing in cases of aggravated murder are costly and overly harsh. But the Oregon District Attorneys Association defends them, saying the laws are working.

“Within one year of adoption, Oregon became the number 1 state in the reduction of violent crimes across the country and today violent crime has decreased by more than 50 percent and Oregon’s juvenile crime rate is well below the national average,” says Tim Colahan, Executive Director of the Oregon District Attorneys Association, in an emailed statement.

Copyright 2018 National Public Radio

Related Stories:

Walla Walla got a Denny’s. Some of its staffers got second chances

Gentry Thorpe, a cook at the new Denny’s in Walla Walla. He’s grateful for employers that practice second chance hiring. (Credit: Susan Shain / NWPB) Listen (Runtime 3:41) Read It

Trial for Bryan Kohberger, man accused of University of Idaho killings, moves to Ada County

Bryan Kohberger, who is accused of killing four University of Idaho students in November 2022, walks past a video display as he enters a courtroom to appear at a hearing

Washington makes a major change to prison sentencing, but not for people already behind bars

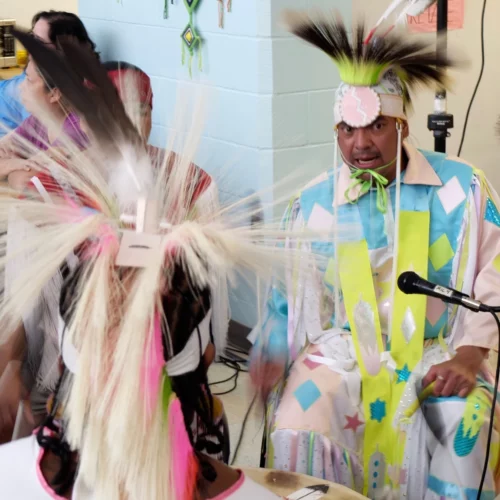

When Travis ComesLast was 20 years old, he was on the run from juvenile detention. He and a friend were looking for ways to get some cash so they could skip town. But during what he describes as a drug deal gone bad, ComesLast shot and killed a man.