Ruiz shares immigrant laborer stories in ‘We Had Our Reasons’

Listen

(Runtime 3:49)

Read

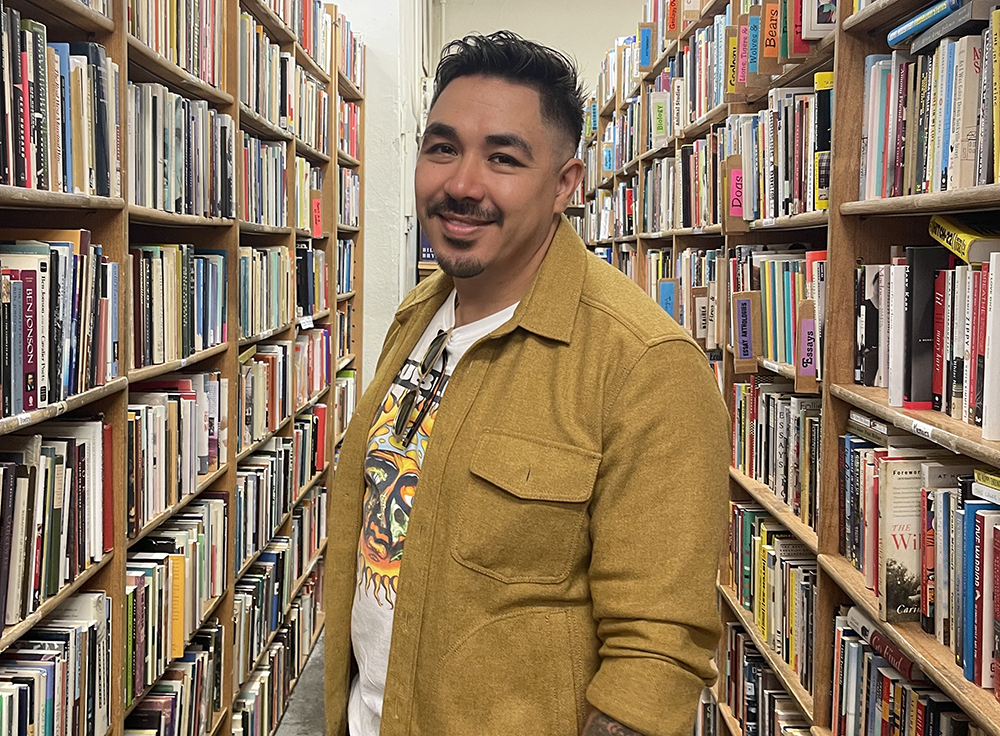

When Ricardo Ruiz first started work on the project that would become an award-winning poetry collection it was often written alone at his desk, late at night when the rest of his family had long since gone to bed.

Ruiz recalled a looming sense of imposter syndrome, and tears shed over not knowing if he would be able to do justice for the stories he was telling.

“All I felt I was capable of, even now still, it’s just like — I just want to go back home and drive a combine,” he said.

The poetry collection is titled “We Had Our Reasons.” It tells stories shared by the poet’s friends and family members about their decisions to leave their home in Mexico for a remote community in the United States.

Ruiz, a first-generation Mexican American who grew up in Othello, Washington, is the son of potato factory workers. He didn’t learn English until elementary school, he said. Like his parents, many of the storytellers in “We Had Our Reasons” are laborers who primarily speak Spanish.

“There’s this storyteller named Abigail in the collection,” Ruiz said. “She’s a member of a church I went to, and I was connected (to) her through a former pastor of mine. Her story is valuable and worthy to be read and told.”

Ruiz’s work as a classically trained poet, he said, was to elevate those voices.

If accolades are any indication, it would seem he succeeded. “We Had Our Reasons” won a 2023 Washington State Book Award, and has been praised as “powerful” and “evocative” by readers. It’s a major accomplishment. But Ruiz said he doesn’t consider the poems, or their success, to be his alone.

The poems’ bylines include the names of the storytellers along with Ruiz’s: “Lorena and Ricardo.” “Centavo and Ricardo.” “Francisco and Ricardo.”

There would be no book of poems, Ruiz said, without the people who shared their stories.

Ruiz said the trust built over years of relationships allowed for deeper truth to come out of the interviews he conducted. He had known one storyteller, Patty, for close to 20 years by the time he interviewed her for the collection.

“The interviews, though formal, were really just conversations with friends,” he said. “I was able to record because (those) years of trust (were) already there.”

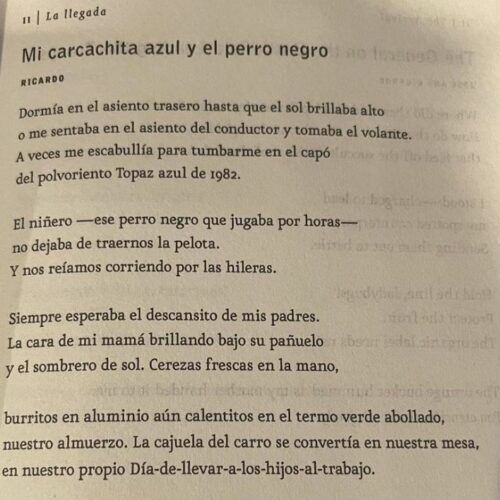

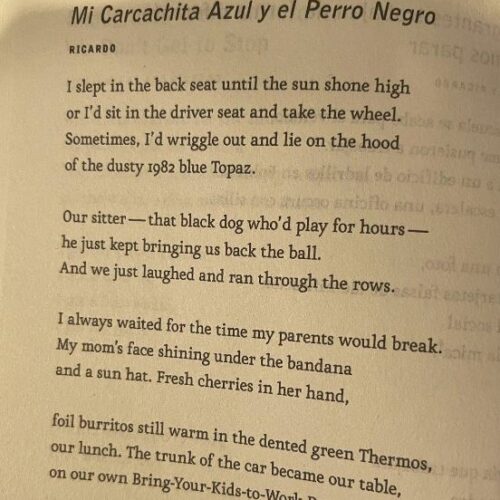

The entire collection is published in both English and Spanish. It was a step Ruiz felt was crucial in the collaborative process with his co-authors.

Ruiz said he knew if he was going to ask the people he interviewed to share their stories, the final work needed to be accessible to them.

“Having the whole collection translated was 100% a must,” he said. “The collection can now live first and foremost in the community that gave it birth.”

At a reading in Lewiston on Friday evening, Ruiz said one of the most meaningful experiences he had after the book came out happened when he visited a school in Kennewick. He received a note from a child in a class he visited.

“It starts off in English and he’s just like, ‘I need to know who your barber is, so when I get to Seattle, I can go and get a tight fade like you have,’” Ruiz said.

But after talking about things like clothes, and hair in English, Ruiz said, the child switches to Spanish. He reflects on a poem Ruiz wrote about his time growing up in Othello, helping his mother harvest cherries and eating lunches over the trunk of a car.

“He goes from talking in English about hair and clothes and sneakers to saying, ‘I’ve never seen myself in a piece of literature before.’ He says, ‘Your poem is so real, because I spend my summers in the fields with my parents. Thank you. Because for the first time, I can see that my story can be told.’”

Ruiz said it was his own curiosity about his family that first led him to do the project. Until he started, he had thought it was unusual that his parents never talked about why they came to the U.S., or what they experienced.

“I started to learn that this isn’t unique to my family,” he said. “So many families there don’t speak about these really traumatic events and issues.”

Part of his hope for the collection, he said, was preserving the stories he recorded for the next generation to learn about where their family came from, and the sacrifices their grandparents made.

One of the poems, “Silent Crossing, Sleeping to the Other Side,” tells the story of a woman named Lorena and what she experienced bringing her child across the U.S.-Mexico border.

Recording: Silent Crossing, Sleeping to the Other Side (Runtime 0:28)

Ruiz said his children, now high schoolers, are preoccupied with the day-to-day pursuits of being a teenager. Things like football, track and field, and video games.

“Rightfully so,” he said. “They should be children and have that freedom to live in their world and in their youth, but I really wanted to hold space for these conversations, so when they’re ready … there’s first-person accountings from the storytellers themselves.”