U.S. Voting System Remains Vulnerable 6 Months Before Election Day. What Now?

PHOTO: Texas, where Austin City Hall was an early voting center, was the first state to go to the polls in midterm primaries in March. Russian interference in 2016 elections looms large over this year’s voting. CREDIT: DREW ANTHONY SMITH

BY MILES PARKS

As America heads toward the 2018 midterms, there is an 800-pound gorilla in the voting booth.

Despite improvements since Russia’s attack on the 2016 presidential race, the U.S. elections infrastructure is vulnerable — and will remain so in November.

Cybersecurity expert Bruce Schneier laid out the problem to an overflowing room full of election directors and secretaries of state — people charged with running and securing elections — at a conference at Harvard University this spring.

“Computers are basically insecure,” said Schneier. “Voting systems are not magical in any way. They are computers.”

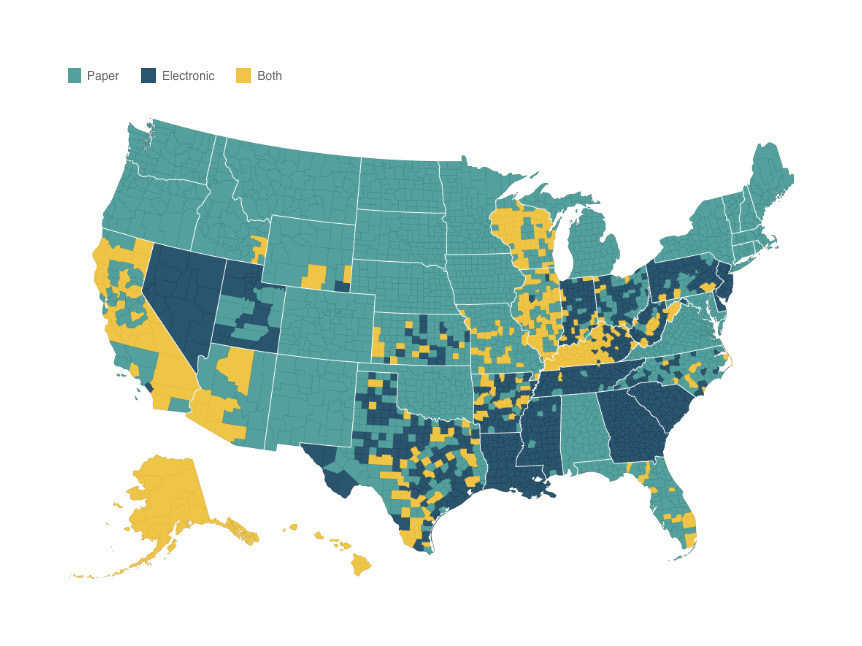

Despite improvements since Russia’s attack on the 2016 presidential race, the U.S. elections infrastructure is vulnerable — and will remain so in November. CREDIT: RENEE KLAHR AND BRITTANY MAYES

Even though most states have moved away from voting equipment that does not produce a paper trail, when experts talk about “voting systems,” that phrase encompasses the entire process of voting: how citizens register, how they find their polling places, how they check in, how they cast their ballots and, ultimately, how they find out who won.

Much of that process is digital.

“This is the problem we always have in computer security — basically nobody has ever built a secure computer. That’s the reality,” Schneier said. “I want to build a robust system that is secure despite the fact that computers have vulnerabilities, rather than pretend that they don’t because no one has found them yet. And people will find them — whether it’s nation-states or teenagers on a weekend.”

Sen. Marco Rubio, R-Fla., who sits on the Senate intelligence committee looking into Russia’s attack on the 2016 election, warned elections officials in his state not to be complacent.

“I cannot emphasize enough the vulnerability,” Rubio said, according to the Tampa Bay Times. “I don’t think [election officials] fully understand the nature of the threat.”

Talking in public about these dangers is a tough balancing act. Transparency in elections is a key component to a working democracy — but election officials want citizens to vote, so they have to portray confidence in the system.

There remains no evidence, as lawmakers and election heads often point out, that any votes were actually changed in the 2016 election.

But the Department of Homeland Security says Russian hackers did break into the registration system in one state, Illinois; steal the username and password of an election official in another, Arizona; and targeted or probed the voting systems of at least 21 states.

So in the span of just two years, officials have gone from arguing that their systems are completely secure to talking openly and clearly about the specific issues that exist and working to fix them.

But a lack of time and resources means heading into the 2018 midterms, American voting systems remain vulnerable, and as Rubio noted, there’s no synchronicity among states and jurisdiction about where the country is in terms of security.

The doomsday scenario

Voter registration databases were being breached. Pundits were loudly questioning the integrity of the election. Americans’ confidence that their votes would be counted fairly and accurately hung in the balance — with widespread chaos looming just on the horizon.

Elections officials from more than 35 states huddled in groups; every time they decided to fund a new resource or deploy a new strategy, news of a new vulnerability sprouted. Reporters hounded for answers, as government employees received highly targeted phishing emails designed to coax their passwords. Simultaneously, a virus penetrated government devices by coming through the printers, which were connected to the Internet.

It was voting problem whack-a-mole. The way the election directors handled the pandemonium would determine the future of American democracy.

Luckily, this time, it was only a drill.

The 150 or so officials gathered at Harvard University for a worst-case scenario exercise — meant to push the officials’ abilities to prepare and react to a broader attack than the one America saw from Russia leading up to 2016.

Arizona’s director of elections, Eric Spencer, an Iraq war veteran, compared the preparations he and his team are making to his training as an infantry officer.

“We always trained harder in the United States for combat to make it easier when we got overseas, and I see this as the same thing,” he said. “[Crisis scenarios] were nearly nonexistent a few years ago. In 2016, before we got information that elections were subject to foreign interference, it was in the back of our mind, but now it’s probably the No. 1 item in our mind.”

Most of the focus so far has been on the more than dozen states still using electronic voting machines that don’t provide a paper backup trail; experts say these machines could allow potential hacks or even technological glitches to go undetected.

In its most recent spending bill, Congress has allocated $380 million for voting security, but the funding will be distributed across all 50 states by population in a way that won’t necessarily address the vulnerabilities of electronic voting machines anytime soon.

In fact, it isn’t clear how much of a dent that money will make overall because no one, including the federal government, knows for sure how much American elections cost.

“Figuring out the true cost of election administration in this country is the white whale of the discipline,” said Doug Chapin, an elections researcher at the University of Minnesota. “I don’t think we even have a really good estimate …. which is why it can be difficult when policymakers, say ‘OK, how much do you need?’ Usually the answer is ‘more.’ ”

The needs are not equal

“Some states are much better off when it comes to protecting their elections systems. And remember, the Russians in particular don’t have to attack every state, they’ll go to the weakest link,” said Eric Rosenbach, director of the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs leading the security exercises, to the Senate homeland security committee. “All they have to do is undermine trust in the system and confidence in the outcome.”

But these issues are bigger than the security of the machines that voters use.

(Interactive: How secure is your vote?)

“The focus regarding the new election security funding seems to be disproportionately focused only on paper ballots and audits. Those are very important, but it will also be nearly impossible to implement these changes prior to 2018,” said David Becker, the executive director of the Center for Election Innovation and Research.

“Meanwhile, other areas of security — voter registration database security (the one area where we know there was one breach in 2016), staff training (proper login protocols, spear-phishing education, etc.), hiring of skilled technical staff — are all just as important and could be done immediately.”

There are questions about whether a subsequent attack might target systems at that level: Rather than trying to change individual votes, a cyber-adversary might try to erase or change all the registration documents in a particular place on Election Day, just to cause chaos. Rep. Mike Conaway, R-Texas, has warned about the danger of this kind of “cyber-bomb.”

Election officials in the more than 10,000 voting jurisdictions are tasked with tackling it all, with differing resources at their disposable. Harvard’s Belfer Center released a playbook for actionable, and often cheap, cybersecurity tips.

And March’s exercises were framed as “train the trainer” workshops, with the hope that the election directors present would then go back to their respective states and localities and run similar drills.

Experts often talk about the simple human element of cybersecurity — being able to spot a phishing email or choosing a strong password. After all, many voting jurisdictions have small information technology departments that may also be responsible for running other city and town infrastructure — they aren’t resourced to defend against an attack by a nation-state.

“It’s going to be a real culture shift; it’s going to have to be something we repeat over and over again until it becomes ingrained in our every day activity,” said Jennifer Morrell, the deputy of elections and recording for Arapahoe County, Colo.

“Most of the conversations around this have been your state and local directors, and now we’ve got to filter that down — it’s going to take a little while.”