New technology helps forensic scientists, police do more with less DNA

Listen

(Runtime 3:47)

Read

A grant from the Bureau of Justice Assistance recently gave Idaho State Police funds they are using to help solve cold cases.

Advancements in DNA technology helped solve one Idaho woman’s case that had hit a dead end. The new funding will help police solve more cases like hers.

In 2003, a 19-year-old college student, Naomi, was kidnapped at a Walmart in Idaho. Police use only her first name when referring to the case to protect her identity.

Her boyfriend at the time was stationed at the Air Force Base in Mountain Home. He had a cold and she went to Walmart to purchase medicine for him.

“She ended up becoming a kidnapping rape victim by a set of circumstances she had no control [over],” said Vickie Gooch, who has been an Idaho State Police detective for 33 years and worked on this case.

The people who committed the crime had already planned it, Gooch said. It was a truck driver and his son, later arrested for the crime and convicted.

After grabbing her in a Walmart parking lot that June, they raped her for five consecutive hours while threatening to kill her. Afterward, they left her 13 miles from the Oregon state line on the Idaho side.

“I got the case because it happened on the interstate and I worked for the State Police,” Gooch said.

Gooch worked on the case but had no leads, she said. The woman didn’t know her offenders. Her hands were duct taped. Even though she was blindfolded, she used the small gap under the bridge of her nose to gather details about her surroundings and her attackers.

Still, the information Gooch had wasn’t enough and the case went cold.

Seven years later, science helped solve the case. A DNA scientist at the Idaho State Police Forensics Laboratory in Meridian called Gooch. They had found information on a John Doe from the Naomi case.

One of the suspects, the truck driver’s son, Douglas Steinemor, was arrested in Florida on drug charges.

Gooch went to Florida to interview the man who kidnapped Naomi at 19. She was 27 by then. He claimed the furthest West he had ever been, was Iowa. “Well, your seminal fluid made it to my victim in Idaho,” Gooch said.

Gooch said Steinemor asked her what the punishment for rape is in Idaho.

“You’re going to be put to death for what you did to Naomi,” Gooch said.

In 2003, rape was not a capital offense in Idaho but kidnapping was.

“I left the jail because he wasn’t going to cooperate,” Gooch said. “20 minutes later, he said, ‘I’m going to tell you what happened,’ and he gave up his father.’”

Steinemor gave the name of the trucking company his father Hans Holsapple worked for. Gooch called the criminal analyst at the state lab to find him. He was already in the system.

The analyst told her Holsapple was locked down for a logbook violation in Branford, Connecticut, a port of entry. “She told me I had four hours before that violation lifted or I was going to lose him,” Gooch said.

She called the Connecticut State Police and sent a warrant.

Just before 6 a.m., right before his hold expired, police knocked on Holsapple’s door with guns drawn.

Detective Vickie Gooch at the Idaho State Police headquarters in Meridian, Idaho. (Credit: Aaron Snell / Idaho State Police)

“When he opened the door, he said, ‘This is about what happened in Idaho, isn’t it?’” Gooch said.

Using DNA from Steinemor and the Combined DNA Index System (CODIS), a DNA database that law enforcement uses, Gooch was able to confirm that Steinemor was John Doe No.1 in Naomi’s case.

Steinemor is serving 25 years and Holsapple 30 years at the Idaho Department of Corrections.

Today, Naomi lives in Texas with her husband, the boyfriend she went to get cold medicine. The two married and now have a family.

New funding will help solve cold cases throughout Idaho

Funds from the Bureau of Justice Assistance grant give Idaho State Police funds over a period of three years that are being used to help solve cold cases like Naomi’s.

“Otherwise, we would have never identified the individual,” said Matthew Gamette, the Idaho State Police Forensics Services Laboratory systems director. Police solved her case because DNA matched a convicted offender’s sample in Idaho through the CODIS database.

The techniques for solving cases using DNA have been getting more sophisticated with time. The grant ISP is using is part of the National Sexual Assault Kit Initiative, a program through the Bureau of Justice Assistance to help transform how law enforcement handles sexual assault cases.

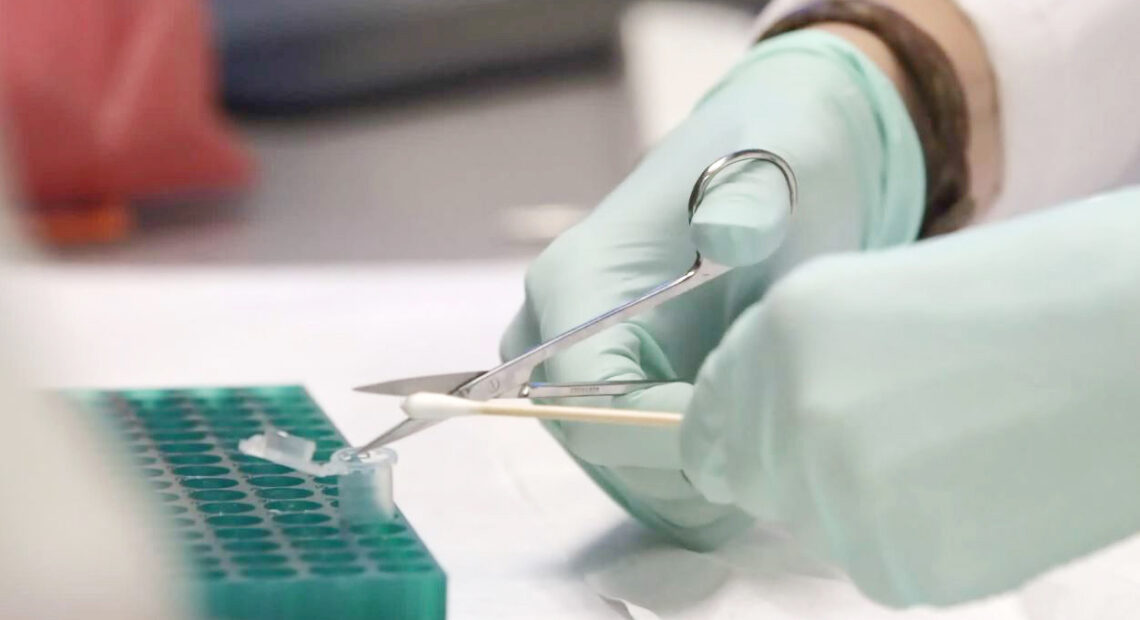

The next level of DNA advancement is sometimes called “next generation sequencing,” Gamette said. He said the sensitive and sophisticated technology allows forensic scientists to do more with less DNA.

“What we’re also looking at, is more sequencing in the human genome and looking specifically at that individual’s DNA. Then making use of that technology by searching a genealogical database,” Gamette said.

Commercial databases such as AncestryDNA and 23andMe have become a popular way for people to find out more about their ethnic history and health traits. When signing up for the services, Gamette said, very often, people check a box that says, “I’m willing to help law enforcement search my data to potentially identify other perpetrators of crimes,” which has helped expand genetic leads for law enforcement.

Using these DNA techniques is not without its challenges, however.

Despite advancing technology, the methods of gathering and using DNA in high-profile crime cases sometimes come under scrutiny. So, it’s important that people give their permission for their DNA to be used, Gamette said.

For example, DNA evidence has been a point of contention between the prosecution and the defense in the case of Bryan Kohberger, who is charged with the murders of four University of Idaho students in November 2022 in Moscow. Investigators were able to match DNA gathered from the knife sheath found next to one of the victims to a man with “familial DNA” gathered from trash at the Kohberger residence in Pennsylvania, according to the affidavit. Kohberger’s defense team has argued evidence against him, including DNA, may have been gathered improperly.

States have their own DNA databases but CODIS is a way to link crimes to previous offenders and people who have been arrested in multiple states.

When the database doesn’t go far enough, molecular genealogy or newer emerging technologies can help police investigate further, Gamette said.

ISP is using these new techniques to help agencies across the state solve cold cases and find violent homicide offenders, Gamette said.

Matthew Gamette stands at his desk in the Idaho State Police Forensics Services Laboratory in Meridian, Idaho. (Credit: Aaron Snell / Idaho State Police)

If someone uses a gun to commit a crime, the chances are, that person loaded bullets into the weapon. The heat and gasses from the gun being fired make it nearly impossible to recover a fingerprint, Gamette said.

A new instrument can now look at the oxidation of the metal and lift a fingerprint from the bullet cartridge, even after the gun has been fired, Gamette said.

“It’s a really exciting time in forensics,” said Gamette.

In addition, the new National Integrated Ballistic Identification Network will allow investigators to find which guns are tied to Northwest crimes.

The database allows investigators to identify cartridges and upload the information into the system that could link the weapon to different suspects or locations across state lines.

Special testing can also be done on overdose deaths from drugs such as Fentanyl. Forensic scientists can create a map of drug deaths at the state and national level, so detectives can focus on hotspots.

“We’ll be pulling blood from overdose victims. We’ll be analyzing it in the lab with a rapid response,” Gamette said. “This kind of intelligence work has never been done from a public safety and health approach.”