Northern leopard frogs growing leaps and bounds at Northwest Trek, preparing for re-release in the wild

Listen

(Runtime 3:50)

Read

At Northwest Trek in Eatonville, Washington, there are about 300 northern leopard frogs, named for their spotted skin, swimming around in four tanks and getting ready for their new home.

The frogs are part of a conservation project that Northwest Trek is partnering with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, the Oregon Zoo and Washington State University on. The goal is to restore this native species, which became endangered in the state in 1999.

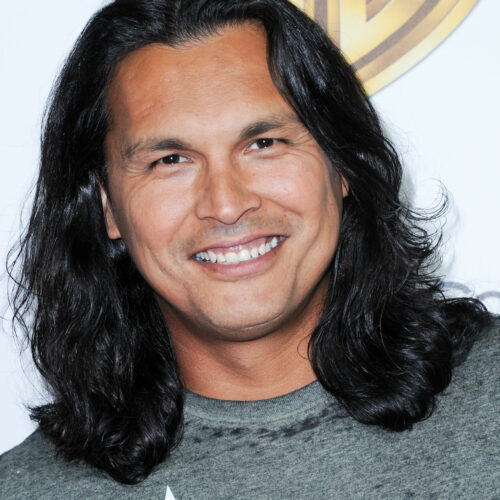

The frogs are found in all provinces of Canada, and northern states from New England to Washington, western states like Colorado, New Mexico and Arizona. They are one of the most widely distributed amphibians in the Western Hemisphere. Assistant Curator Dave Meadows serves the frogs their meal of live crickets. (Credit: Lauren Gallup / NWPB)

Assistant Curator Dave Meadows serves the frogs their meal of live crickets. (Credit: Lauren Gallup / NWPB)

Since the 1950s, populations have been decreasing, according to Lindsay Nason, northern leopard frog biologist for the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. Western states like Montana, Oregon and Washington and some Canadian provinces have reported severe population declines, Nason said.

“In Washington, the northern leopard frog previously inhabited at least 18 general areas in eastern Washington but now only one population persists,” Nason said.

Predation and habitat conversion has harmed the species. Human development for agriculture and dams has changed water flows, and the frogs need access to bodies of water to survive. Adding to that, the invasive American Bullfrog from the eastern side of the U.S. has spread across the west, wreaking havoc on the species.

“They’re a pretty big problem in the western United States,” Nason said. “They’re out competing and predating upon, so basically they’re eating and taking resources and space from our native amphibians that are supposed to be here in the Northwest.”

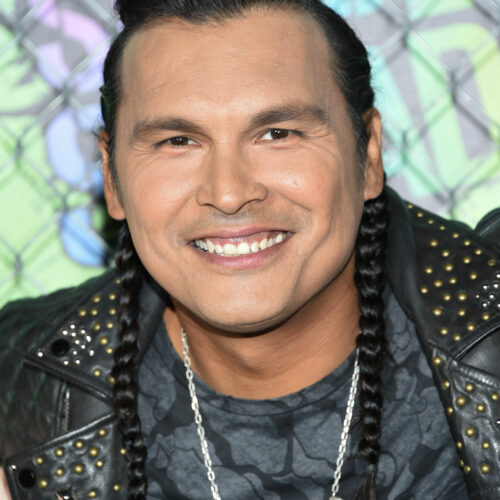

Now, scientists estimate there are only 250 breeding frogs in one area of the state, in the Potholes Reservoir by Moses Lake.  Northern leopard frogs are one of the most widely distributed amphibians in the western hemisphere. (Credit: Lauren Gallup / NWPB)

Northern leopard frogs are one of the most widely distributed amphibians in the western hemisphere. (Credit: Lauren Gallup / NWPB)

Conservationists are working to ensure the survival of the species. Nason said the species is an important part of the region’s native biodiversity.

“If we do not establish more populations of these frogs and expand their range, they will likely become extinct in the state of Washington,” Nason said.

Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife biologists collected egg masses of the frogs from the Potholes Reservoir area to take to Northwest Trek, where staff are raising the amphibians until they’re fully formed frogs. In mid-July, many of the frogs were already fully metamorphosed.  The frogs are being raised here until they’re fully metamorphosed, then they’ll be released back into the wild. (Credit: Lauren Gallup / NWPB)

The frogs are being raised here until they’re fully metamorphosed, then they’ll be released back into the wild. (Credit: Lauren Gallup / NWPB)

Dave Meadows, assistant curator at Northwest Trek, is now feeding them a daily diet of live crickets.

“This head starting program gives them a better chance to make it to adulthood and help increase the wild frog population,” Meadows said.

In mid-August, the frogs will travel to the Columbia Wildlife Refuge, near Royal City, and be released.. That’s done to increase the likelihood the species will survive and thrive in near areas, a process known as species reintroduction.

Marc Heinzman, zoological curator for Northwest Trek, said a disease or mass predation could wipe out the population in one location. He said having pockets of the animals in different parts of the state ensures their survival long-term.

Before they’re released, biologists will weigh and measure the frogs. Scientists will also put different identifiers on them, including elastomer dye, a colored-liquid injected into the animal that cures into a solid to be visible for tracking. The dye is not harmful to living tissue. Some of the bigger frogs will be fitted with tiny backpack transmitters that monitor movement. These will fall off as the frogs grow, Meadows said.

Experts said these 300 frogs could make a big difference for the species.

“A single female could be responsible for another 5,000 or 6,000, or more, leopard frogs,” Meadows said. “So there’s a big impact of being able to head start these guys in releasing them.”