How This Washington Family Brought Oysters Back From The Brink

Oysters are a cornerstone of Pacific Northwest cuisine. But there was a time when our region’s oysters were in trouble, all but obliterated by over-harvesting and pollution.

Then a Japanese immigrant helped turn things around.

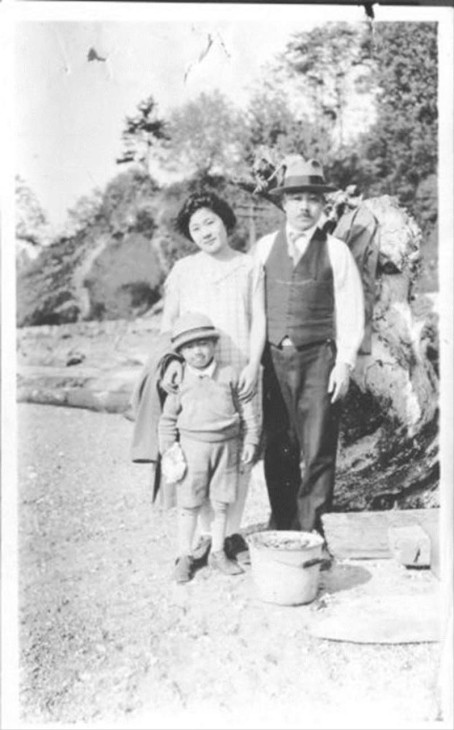

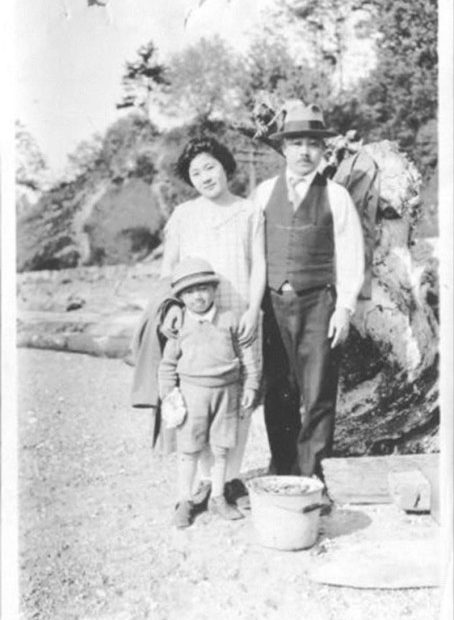

His name was Masahide Yamashita, and he came to Seattle from Japan in 1902.

“He was only 19 years old,” said Patrick Yamashita, Masahide’s grandson. “And I think he came here in part because he didn’t want to get drafted into the army in Japan.”

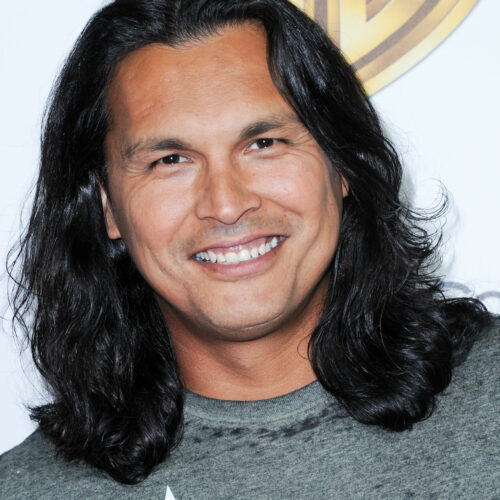

Patrick, 53, told the story while looking through old family photos with his 95-year-old father Jerry. He explained that Masahide eventually got into the import-export business.

“He imported pearls from Japan at one time,” said Patrick. “He imported watch crystals from Japan. He exported motorcycles from New York to Japan before World War II, believe it or not.”

But none of those ventures really stuck. Then along came oysters.

In the early 1900s, Olympia oysters, native to the region, were in near decline. Shelly Solomon, a biologist and filmmaker, said the culprit was over-harvesting and pollution.

“And the pollution was related to the pulp and paper industry,” she said. “And at that time, there were soft laws with regards to effluent in the creation of pulp and paper. And so this toxic effluence, they just couldn’t survive.”

Patrick Yamashita, left, laughs with his father Jerry while posing for a portrait on Friday, Feb. 9, 2018, at his home in Seattle. CREDIT: MEGAN FARMER/KUOW

Solomon and her cinematographer husband Kent Cornwall made a documentary called “Ebb and Flow,” which tells the Yamashita family’s story. Solomon said the industry tried bringing in oysters from the east coast, but those didn’t survive.

“Some Japanese people in Pike Place Market said, maybe we could bring in some from where we lived in Japan,” she said.

They brought small quantities of adult oysters from Japan. But those didn’t survive, either. They were about to abandon that idea when they noticed the babies — or the seeds attached to the shells — were living.

Still, the travel time from Japan was a major hurdle. Solomon said that’s when someone approached Masahide for his import-export know-how.

“He said, I could move the ships around and get them directly to where they were growing them,” Solomon said. “So that saved a lot of time.”

Patrick Yamashita said the seeds were specially packaged to help them survive the long voyage.

“The seeds were placed in wooden boxes, and then covered in straw or rice mats, and then they poured the sea water on top,” he said.

Between 1930 and 1938, Masahide sold thousands of cases of Japanese oyster seeds to Northwest shellfish farmers. The oysters thrived in the Northwest, and Masahide formed a cooperative with the Japanese farmers that helped set consistent pricing for seeds.

“I think [the oyster] found its new home,” Patrick said. “So much so that people nowadays think … that’s the oyster that’s always grown here. But originally it came from Japan.”

Masahide stopped selling seeds and got into the shellfish business with his son Jerry, who was then 19 years old.

The family leased tidelands to grow oysters. They were building their business when World War II broke out, and life as they knew it turned upside down. Jerry remembers once trying to stop a man from stealing his family’s oysters from the tideland.

“I said, all of these oysters are our oysters. We planted them so that we could harvest them. And the man says, yeah, well you’re not going to be around here much longer anyway.”

Jerry Yamashita, left, with his wife Dorcas, on their wedding day in 1958 in Seattle. Courtesy of Patrick Yamashita

It was an ominous foreshadowing. Masahide’s connections to Japan through his import-export business made him a target for federal authorities.

“There were FBI agents that showed up to where my dad’s family were,” Patrick said. “Eventually the FBI took my grandfather to a camp in Montana.”

The rest of the family tried to cope without Masahide, not knowing when they’d see him again. Later, the Yamashitas, along with more than 100,000 Japanese Americans, were forcibly removed. The family was sent to Tule Lake in California where they were incarcerated for three and a half years.

After the war, the Yamashita family returned home to Washington. Not everyone welcomed them.

“There were signs on businesses: ‘No Japs,’” Patrick said. “So it was challenging. But at the same time, there were very kind people … There was a neighbor that brought, I think, dahlia bulbs for flowers and something else just to say welcome.”

Jerry Yamashita points to a group photo where his father, Masahide Yamashita, stood in the center, on Friday, Feb. 9, 2018, at his home in Seattle. CREDIT: MEGAN FARMER/KUOW

The family tried to return to oyster farming. Some friends had agreed to take care of their seeds, Jerry said.

“And they said that they would plant the seed on their own ground, so that when you come back, why, we’d have the oysters for you,” he said.

Also after the war, the region’s thriving Japanese oyster was renamed the Pacific oyster.

After 76 years in the business, Jerry Yamashita retired in 2012. Patrick and his siblings stay involved in the shellfish industry by leasing out their tidelands. And Patrick said he often goes out to harvest, since he likes sharing them with friends and family.

“It gives me great pleasure to be able to share of what we have,” he said. “And that’s what mom and dad have always done as well.”

Jerry added: “There’s nothing better than oysters!”

Copyright 2018 KUOW

Related Stories:

Rural areas hit hard by food insecurity, study finds

Joe Tice, the Tukwila Pantry’s executive director, stocks tables with canned goods at the food bank in Tukwila, Washington. (Credit: Lance Cheung / USDA) Listen (Runtime 1:03) Read Before she

Funding for local poet laureate inspires international collaboration

At food establishments across Redmond, diners this month will find a unique accompaniment to their orders; poems.

Penned by local writers as well as poets from international Cities of Literature, the poems expound on community, harvest and lineage. Redmond’s poet laureate, Ching-In Chen, is leading the project, called Read Local Eat Local, It kicks off on Thursday Sept. 19 in conjunction with the Downtown Redmond Art Walk.

A 105-year-old receives her degree after waiting 80 years

Virginia Hislop, of Yakima, recently participated in the commencement ceremony at Stanford University. She earned a master’s degree in education in 1941. (Credit: Annie Warren / NWPB) watch Listen (Runtime