Native educators teach cultural competency and respect to end health care disparities

Listen

(Runtime 4:03)

Read

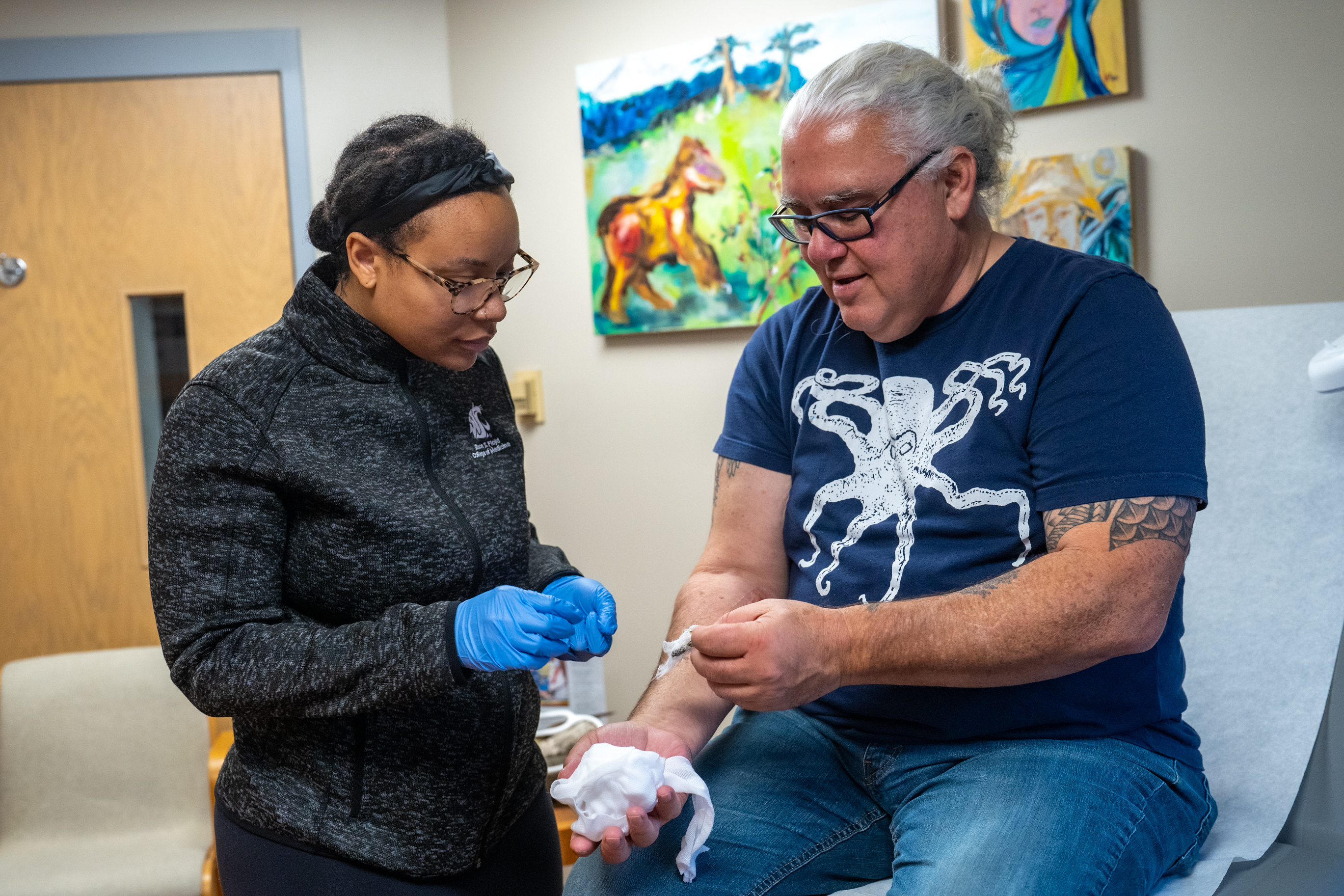

When medical students or health care providers enter a simulation at the Center for Native American Health on Washington State University’s Spokane campus, they’re running through a situation that already happened to a Native American patient who faced real-world health consequences.

In one case, a doctor might see a “patient” with high levels for liver enzymes. That could be indicative of several possible health issues, but if a patient is Native, doctors are more likely to have one specific response based on stereotypes about Native people.

“Often what happens is that a provider may walk in and basically tell a Native individual, ‘You need to quit drinking, your liver enzymes are really high,’ instead of really inquiring [about] what is going on,” said Carrie Gigray, the Indigenous clinical simulation educator at the Center. “A lot of our cases are based off of real circumstances that have happened in someone’s life that we know.”

In other cases, a provider might encounter simulations about how a patients’ spiritual beliefs or cultural etiquette affect communication, learn about how food scarcity on reservations could affect patients’ ability to follow diet protocols, or treat someone using plant medicine on an, “injury.”

“Sometimes students will ask all about it, sometimes students won’t ask anything about it,” Gigray said, referring to plant medicines. “So then you have this facilitated discussion of, ‘Hey, tell me why you didn’t ask about that weird green stuff on the wound and on the bandage?’ And then we talk about that.”

Those conversations are where the real learning happens, Gigray said. They provide a safe environment for providers to ask questions they might not be comfortable asking a real patient and learn how to communicate effectively and respectfully.

Since starting last fall, about 100 students and providers have gone through those medical simulations. This fall, WSU will offer an Indigenous Healing Perspectives certificate using those simulations.

Naomi Bender, director of the Center for Native American Health and Native American Health Sciences, said the Center’s goal is to end the negative health disparities that Native people face, such as increased risk of mental health problems, heart disease and diabetes.

Bender, an Indigenous Quechua woman, said practitioners of Western medicine and those doing medical simulations, historically have disregarded Native peoples’ perspectives and knowledge.

While historical injustices caused some health disparities, others happened because of medical systems that failed Indigenous people, Bender said.

“It was truly my goal, as the director, to have a space for the first time in the United States that did not belong to western medicine, but belonged to the people,” she said. “A space where our Native and Indigenous voice and our ways of knowing could be the primary source of educating and informing.”

Gary Ferguson, director of WSU’s Institute for Research and Education to Advance Community Health, said although western medicine is sometimes considered at odds with Native peoples’ medicine and knowledge, there’s room for both.

“More and more, we’re realizing that the wisdom of our tribal nations of the medicine that came, and continues to come, from Indigenous people is incredibly powerful and much needed in the world today,” he said.

Ferguson, an enrolled member of the Qagan Tayagungin Tribe of Alaska, said Native peoples have lived on the land for hundreds and sometimes thousands of years. His and his colleagues’ work aims to honor those cultures and Indigenous knowledge while integrating them with the best of western medicine.

“Just think about that, the wisdom to have lived and thrived in the medicines and the foods and the cultures that have allowed that to happen … there’s something there,” he said. “I feel like having a respect for that amazing resilience, that’s what we bring to our clinical spaces.”

Jerry Crowshoe, assistant director of the Native American Health Sciences program and member of the Piikani Nation, said Native belief systems and western science often say the same thing in different ways.

When his blood pressure got too high, he said, his doctor told him to eat fresh foods and avoid frozen and processed meals. Through Indigenous teachings, he learned that if people take care of the Earth, it will take care of them in the form of traditional foods like salmon, deer, berries and other plants.

“I didn’t fulfill the obligation, then my health started going down,” he said. “So you can see that western medicine, what my doctor said over there in his clinic, and what my grandfather said. say the exact same thing, they just have a different language and have a different way.”

Bender said it wasn’t easy to bring the Center, and the services it now offers, into being. The programs that exist today are the culmination of years of work and resistance.

“This is years and years of the doors being shut down on us and not being provided the space, or the grace to share a voice,” she said. “And I pray about it. And I have to just be patient and continue on my way, and find a means and a way to keep walking 10 steps forward, like my ancestors, no one stopped. We’re still here.”

Bender said her ultimate goal for the Center, and the education it provides, is to end health disparities. Her goal is to end health disparities perpetuated by health systems, higher education and health care workers.

“If we, here, can be part of that, then I feel like one day, when it’s my time to go on my journey, I’ve done my part.”

This report is made possible by the cooperative agreement with NWPB, the Lewiston Tribune and the Moscow-Pullman Daily News