Spiders, scorpions, Pacific lamprey: kids – and adults – get a peek into Washington’s wild side

LISTEN

(RUNTIME: 1:00)

READ

As a Pacific lamprey suctioned itself onto the side of a small fish tank, its pointy teeth were on full display. The rest of the eel-like fish wriggled about in the water.

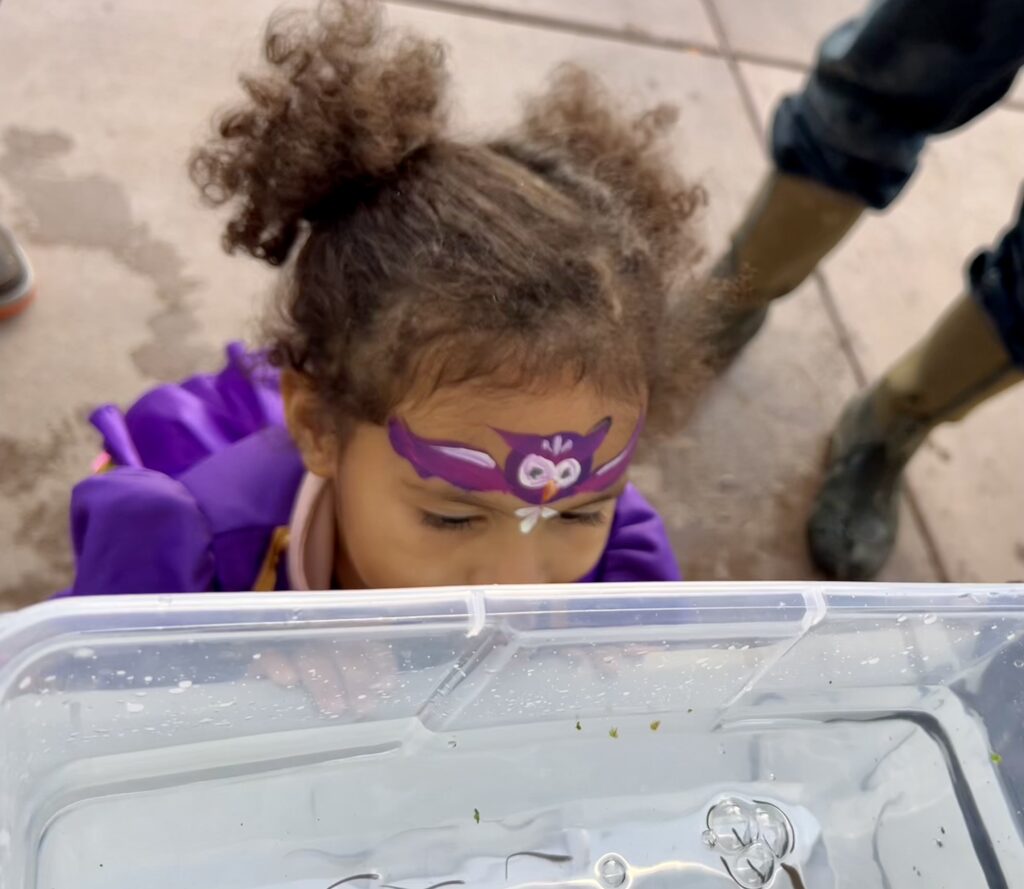

On the other side of the tank’s glass stood 2-year-old Jevencia Marshall, wide-eyed and giggling at the roughly 18-inch lamprey.

Her father asked to touch the fish.

“What in the world? It’s like a snake,” said Andre Marshall, Jevencia’s father, as he placed a couple fingers near the head of the lamprey.

Ralph Lampman, left, shows off a Pacific lamprey, and its teeth, to Andre Marshall, who attended the Screech at the REACH event. CREDIT: Courtney Flatt, Northwest News Network

Ralph Lampman, a Pacific lamprey project biologist with Yakama Nation Fisheries, held tight to the lamprey.

“If I didn’t have gloves on it’d be really hard to grab it,” Lampman said of slick-skinned fish.

The lamprey on display made up part of a Screech at the REACH event Friday in the Tri-Cities that showed off scorpions, beetles, snakes, owls, bats, and coyote pelts to dozens of people.

“The whole idea is that we take the classically spooky around the Columbia Basin, and we showcase how amazing and awesome it is,” said Andrea Constance, museum educator at the REACH Museum.

The REACH Museum curates galleries and programs to highlight the natural and cultural significance of the Mid-Columbia region.

At the lamprey tank, people peppered Lampman with questions, as the lamprey sucked on his arm. It wasn’t painful, he said. Lamprey don’t bite.

“Are those his gills?” Andre Marshall, who attended the event, asked, leaning in to get a closer look.

Jevencia Marshall, 2, looks at Pacific lamprey with her father, Andre. CREDIT: Courtney Flatt, Northwest News Network

“It has seven gills on its side. That’s how they breathe. They don’t breathe through their mouths,” Lampman said.

In Japan, Lampman said, lamprey are called eight-eyed eels because the fish have seven gills and one eye.

Other facts Lampman dealt out: Lamprey typically live to be 15 years old. Lamprey lose their teeth every month – some people at Yakama Nation Fisheries use the shed teeth to make art, including coasters.

As one of the most important cultural foods for tribes, the vitamins and nutrients you can get from eating a single lamprey could meet most of your daily needs.

“You don’t need to eat your vegetables. You don’t need to drink milk,” Lampman joked.

However, the Oregon Health Authority recently issued a health advisory on the amount of lamprey people can eat due to the toxic chemicals that accumulate in the fish.

A death feigning beetle. CREDIT: Courtney Flatt, Northwest News Network

Inside the museum, a table lined with bugs and snakes drew a big crowd of children.

“I want to see. I want to see,” said 5-year-old Kristy Smith, her nose pressed to a plastic case that held two hissing cockroaches.

“I like all of them,” Kristy said of the bugs on display. “I didn’t want to touch the snake.”

At the booth, Dale Jansons, an entomologist known as Bug Guru, let the kids – and adults – hold a death feigning beetle.

“It sounds scary, but the second word is feigning. So, if they don’t like you, they flip over,” Jansons said.

Andres Tissell, 3, looks at bugs at the Bug Guru table. CREDIT: Courtney Flatt, Northwest News Network

The death feigning beetles have very tiny hairs on its back, so they drink from the air, Jansons said.

Also on display: Jeffrey the ball python, whip spiders, and northern scorpions, which Jansons said he caught at a local dog park.

“The sting is less than a bee,” he said.

Northern scorpions, as their name suggests, are the only scorpions that live this far north, Jansons said.

“The ones that get me, even as an entomologist, are the giant centipedes,” Jansons said.

At the lamprey booth, Andre Marshall looked at the juvenile lamprey with his daughter. The pencil-sized lamprey stay in rivers for up to seven years before they migrate to the ocean.

“I’m glad I saw this,” Andre Marshall said. “Who would have known?”

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story misspelled Andrea Constance’s name and Screech at the REACH.