Weeds And Herbicides Puts An Organic Farm At Odds With Neighboring Growers In Oregon

Weeds. Nobody wants them. But, lately, the subject has taken over everything in rural Sherman County — the talk around town, email servers, even the local high school gymnasium.

At issue is whether a large organic farm, Azure Standard, is letting its weeds spread onto neighboring property — and whether the government should do something about it. Neighboring farmers say the weeds have crept onto their fields, costing them time and money to control the problem.

The weeds include rush skeleton, Canada thistle, morning glory and whitetop.

“These are bad weeds. They just take over,” said Bryan Cranston, a neighboring farmer who grows seed wheat.

This year, after sending notices since 2006, the county stood its ground. A weed district supervisor sent Azure Standard letters, first outlining options — including spraying non-organic herbicides Escort or Milestone — and asking for a weed control plan. County officials say the farm is violating its noxious weed ordinance, which directs growers to “destroy or prevent” noxious weed seeding on their land in a timely manner.

Initially, the church Ecclesia of Sinai at Dufur, which owns Azure Standard’s land, sent back a letter refusing to allow the county to treat noxious weeds on its roughly 2,000 acres in Moro, Oregon.

“The Ecclesia of Sinai at Dufur has not and does not give any jurisdiction to any Federal, State, or County employees to trespass on Ecclesia ground to spray any toxic or poisonous substance at any time. We are happy to work with neighbors and the Weed District, as long as it is in line with Yahweh’s Word (Matt. 22:37-40),” wrote one of the church’s heads, Alfred Stelzer.

Spraying herbicide on a USDA-certified organic farm would mean the farm would have to wait at least three years until it could regain the department’s certification.

County officials say no one ever wanted to forcibly spray an organic farm and that other options — like heavy deep tillage to rip up roots or covering weeds with dark plastic barriers to block their light sources— were presented in a second letter to Azure Standard.

Then came two videos posted to Facebook, imploring people to let the county know about the importance of organic farms.

The issue blew up.

“I initially put it out there because I really felt like the county court, especially, and the people in the county didn’t understand that there was a real need. There are people that really depend on (organic food),” said David Stelzer, CEO of Azure Standard.

Stelzer said he thought 50, maybe 100, calls could help show that others shared his passion for organic crops. He generally keeps off social media. Maybe that’s why he greatly underestimated the power of a post that goes viral.

Calls and emails flooded in from around the Northwest and across the globe — from as far away as New Zealand. As of 4 p.m. Wednesday, county officials said they had received upwards of 57,000 emails. (County commissioners said the most comments they’ve ever received on a single ordinance was about five.)

Their phones rang off the hook. They eventually had to stop answering calls.

At the county courthouse Wednesday afternoon, Commissioner Tom McCoy pulled out his iPhone and clicked open his email app. Blue-dotted unread messages popped up as soon as he refreshed the screen.

“I just now opened my phone, and probably the last time I opened it was about 9 o’clock,” McCoy said. “Those are all new comments.”

They moved a regularly scheduled meeting to the Sherman County High School gym to accommodate crowds who wanted to speak their mind. About 300 people filled the bleachers.

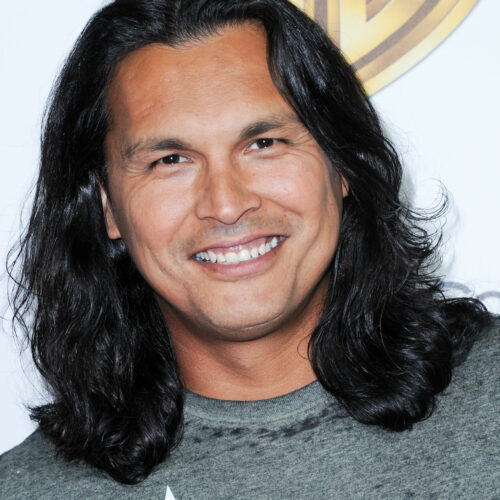

About 300 people filled the bleachers at the Sherman County High School to discuss whether a large organic farm is letting its weeds spread onto neighboring property — and whether the government should do something about it. CREDIT: COURTNEY FLATT

Farmer Bryan Cranston said he’s never seen a weed issue like this during his 12 years of growing seed in Sherman County.

“If I drift a chemical on you, I’d be in trouble,” Cranston said. “Your weeds are encroaching on me.”

Cranston, who lives across a road from Azure Standard, said he’s had to increase his use of chemicals to control weeds on his property — at a cost of an extra $12 to $15 per acre. If rush skeleton were to be found on his property, Cranston said, he couldn’t produce certified seed wheat on that field for up to five years.

It’s an unusual turnabout for organic farming; typically it’s these types of operations that complain about their conventional-farming neighbors who threaten the quality of their crops with drifting pesticides.

Farmers who are criticizing Azure Standard said this issue wasn’t about conventional versus organic, but rather about land stewardship.

“None of us have anything against organic farmers. This is about being neighborly,” said wheat farmer Ryan Thompson.

But Azure Standard operators said they didn’t know any neighbors had issues with them.

“I’m deeply sorry if we’ve hurt you guys,” said Nathaniel Stelzer, who is moving to Moro and will run the company’s operations there — most of the family lives in Durfur, Oregon, about 50 miles away.

The company submitted a weed control plan on Tuesday afternoon, which included options ranging from heavy fertilization followed by deep cultivation in the fall, mowing before seeds form, to acquiring specialized farm equipment that selectively cuts plants and grasses.

“It’s a complicated problem. There’s no easy solution for organic farms,” said David Knaus, an organic agriculture consultant hired by Azure Standard. “It can be done. The thing they need to do is stay after it.”

And if they don’t? County residents say the weeds can’t go on like this.

“I hope they put these organic methods into use and never have to spray a single drop, but I urge the (Sherman County) court to enforce the ordinance to the fullest extent if it’s not done in a timely manner,” said wheat farmer Logan Padget.

Others at the meeting said Sherman County could use this media attention for good.

“(Organic) is going to be the way of the future,” said Dufur resident Benjamin Brewer. “We should support the weed board to study ways to control organic agriculture. We have a lot to learn. We can decide then as a community and be on the map for future generations, saying, ‘That county stood up and supported organic agriculture.’”

For his part, Azure Standard CEO David Stelzer said he doesn’t want weeds on his property either. But right now those weeds are helping pull up needed nutrients in the soil. Once the weeds are more controlled, methods like crop rotation could help with that issue, he said.

“I want to be able to knock them out, but I’d like to do it the right way,” David Stelzer said. “The last thing I want is to kill them with a deadly toxic chemical.”

The organic farm submitted a weed control plan late Tuesday afternoon. Its operators will meet with county officials and weed experts in the next 10 days to see if that plan will work.

“If we can do that, then we can live and let live,” commissioner Tom McCoy said after the meeting.

Copyright 2018 EarthFix

Related Stories:

Rural areas hit hard by food insecurity, study finds

Joe Tice, the Tukwila Pantry’s executive director, stocks tables with canned goods at the food bank in Tukwila, Washington. (Credit: Lance Cheung / USDA) Listen (Runtime 1:03) Read Before she

Funding for local poet laureate inspires international collaboration

At food establishments across Redmond, diners this month will find a unique accompaniment to their orders; poems.

Penned by local writers as well as poets from international Cities of Literature, the poems expound on community, harvest and lineage. Redmond’s poet laureate, Ching-In Chen, is leading the project, called Read Local Eat Local, It kicks off on Thursday Sept. 19 in conjunction with the Downtown Redmond Art Walk.

‘Tastes like hard work:’ Inside a foraging hike on the Kitsap Peninsula

Andrew Pogue, co-founder of Fair Isle Brewing in Seattle, reaches for fireweed leaves on a foraging trip. (Credit: Courtney Flatt / NWPB) Listen (Runtime 3:46) Read One craft brewery in