Pilot Project Aims To Clean Up Some Central Washington Soil Contamination

Read

New homes built in Central Washington could be constructed on top of old orchards, where soils might contain the remnants of pesticides from the early 1900s.

A $225,000 Department of Ecology grant to Chelan County will help pave the way for developers and home builders to more easily seal off contamination, with a pilot project in Manson, Washington, near Lake Chelan.

Around the early 1900s, the pesticide lead arsenate was particularly good at protecting apples and pears from codling moths, which can ruin apples. Years later, the pesticide remnants are particularly good at sticking around in the soil.

In recent years, developers plowed over many former orchards, turning them into neighborhoods, schools and daycares.

Once in the top layers of soil, the pesticide breaks down into lead and arsenic, which never wash away. Lead and arsenic can cause harmful health effects, especially for children.

Children often are exposed to higher levels of contamination because they crawl around on floors and put their hands in their mouths more frequently, health experts said. Lead in children’s blood can cause behavioral problems and lower IQs. Later in life, high levels of arsenic exposure have been linked to heart disease, diabetes and various forms of cancer.

Research has shown lead and arsenic don’t break down in the soil, and therefore, shouldn’t reach the water table. The remnants of lead arsenate sprayed or spilled on the ground 100 years ago is still within the top foot of soil, Frank Peryea, who studied lead and arsenic for decades with Washington State University, told EarthFix in an earlier interview.

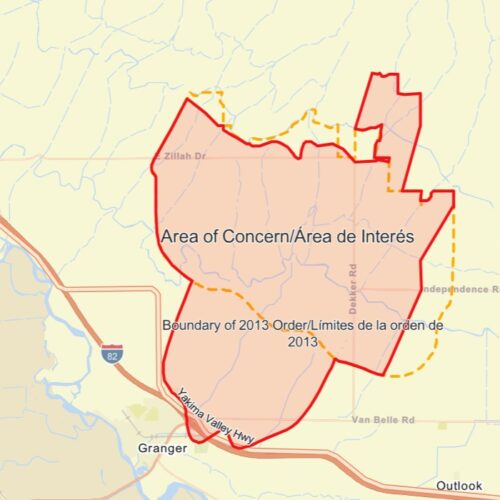

To help track exposure risks, the Washington Department of Ecology has developed maps to show where lead arsenate may have been sprayed, mostly in Central Washington, said Joye Redfield-Wilder, Department of Ecology Central Region spokesperson.

The maps cover tens of thousands of acres across Central Washington.

Nearly 20 years ago, the Washington Department of Ecology began studying lead and arsenic soil contamination from historic spraying. At the same time, the department looked at lead and arsenic contamination in Tacoma near a former smelter.

In Central Washington, people making land-use decisions didn’t always clean up former orchard sites, Redfield-Wilder said.

The department would send a letter stating that proposed developments might be old orchard land and should be tested for lead or arsenic, she said.

“But that didn’t always happen,” Redfield-Wilder said.

Overtime, she said, residents have become more aware of the soil contamination problems in Central Washington.

In 2020, a 34-member workgroup, including planners, developers and county officials, worked to find solutions to Central Washington’s lead arsenate problem. However, the workgroup meetings were closed to the public and reporters. The group released its final report in 2021.

As part of the pilot project, Talos Construction planned a new 5-acre subdivision in Manson, with plans to build 20 separate plots.

Testing showed the area had high levels of lead and arsenic contamination in the soil, Redfield-Wilder said.

To clean up the area, the developers will pave over roads and sidewalks, known as hard capping an area. Hard-capping soil completely seals in the contamination, according to the Department of Ecology.

In the past, developers had trouble finding clean soil, Redfield-Wilder said. Contaminated soil had been moved all around Central Washington for years. Therefore, lead and arsenic could pop up in dirt far away from a former orchard, she said.

The pilot project has already helped track down clean soil, she said.

At the pilot project, property owners will need to cover the contaminated soil on their property, Redfield-Wilder said.

For many property owners, the cheapest way to do that is to cover the ground with gravel, grass or non-contaminated dirt, known as soft-capping an area. Before layering on the clean soil, property owners should place a demarcation fabric to mark where the contamination starts, according to best practice policies.

This subdivision cleanup could be a precedent for developments moving forward, said Mindy Hibbard, the development’s managing broker with John L. Scott Real Estate.

It will be important to be cautious and environmentally friendly moving forward, Hibbard said.

“The cleanup is on consumers’ radar,” she said.

Potential property buyers have come from the east and the west sides of Washington, Hibbard said, and information on the cleanup project has helped educate these potential buyers.

“When a point is brought up to buyers that they may not have thought of, they do more research and are more diligent,” Hibbard said.

Each parcel cost more than $5,000 to clean up, according to a presentation about the pilot project.

While Chelan County considered the project a success, it could be difficult to duplicate without similar funding, said Mike Kaputa, Natural Resources Department director with the county.

To help more developers find clean soil, the Department of Ecology is testing the feasibility of a clean soil bank, which could supply lead- and arsenic-free soil all over Central Washington, Redfield-Wilder said.

A Dirt Alert Map can help people discover if their property is located on an old orchard site.

The Department of Ecology will sample properties for free. To schedule a test, email FormerOrchards@ecy.wa.gov.

If a property is above the healthy levels for lead or arsenic, the department has several steps to take, ranging from removing the contaminated dirt, the most expensive option, to covering the contaminated soil with clean dirt, gravel or grass, the least expensive option.

Homeowners also can reduce exposure to lead and arsenic by taking off shoes at the door; mopping and vacuuming frequently; and planting vegetable gardens in a raised bed, especially root vegetables, according to the department. It’s also important to frequently clean play areas, toys and pacifiers.

Clarification note: This story has been updated. After the story published, a Washington Department of Ecology spokesperson said they misspoke and overestimated the acreage that is covered by the maps. This update has the department’s updated estimate.

Related Stories:

Hazardous chemicals leak into groundwater below Pasco Sanitary Landfill

The thermal treatment system for soil contamination in Zone A of the Pasco Sanitary Landfill. (Credit: Washington Department of Ecology) Listen (Runtime 1:07) Read A closed landfill just outside Pasco,

Inslee approves controversial wind farm near Tri-Cities

Horse Heaven Hills, in southeastern Washington, with Webber Canyon in the distance. Washington Gov. Jay Inslee approved a large-scale renewable energy project along 24 miles of ridgelines in the area.

What is Initiative 2117?

Phuong Brown, a retiree in Walla Walla, received a free heat pump through the Climate Commitment Act. Initiative 2117 aims to repeal the act. (Credit: Susan Shain / NWPB) Listen