Artist’s Black Wall Street Project Is About Tulsa 100 Years Ago — And Today

LISTEN

BY NEDA ULABY

Artist Paul Rucker is fearless when it comes to taking on terrible moments in American history.

“The work that I do evolves mostly around the things I was never taught about,” Rucker explains. Over Zoom, he’s discussing his work in progress, Three Black Wall Streets, which evokes and honors the achievements of Black entrepreneurs and visionaries who created thriving spaces of possibility and sanctuary after the end of the Civil War.

One of them, in Tulsa, Okla., was destroyed by a white mob 100 years ago, on May 31, 1921. The catastrophic attack on what was known as Black Wall Street might be the worst single episode of racial violence in American history, with 35 city blocks of Black community destroyed and flattened.

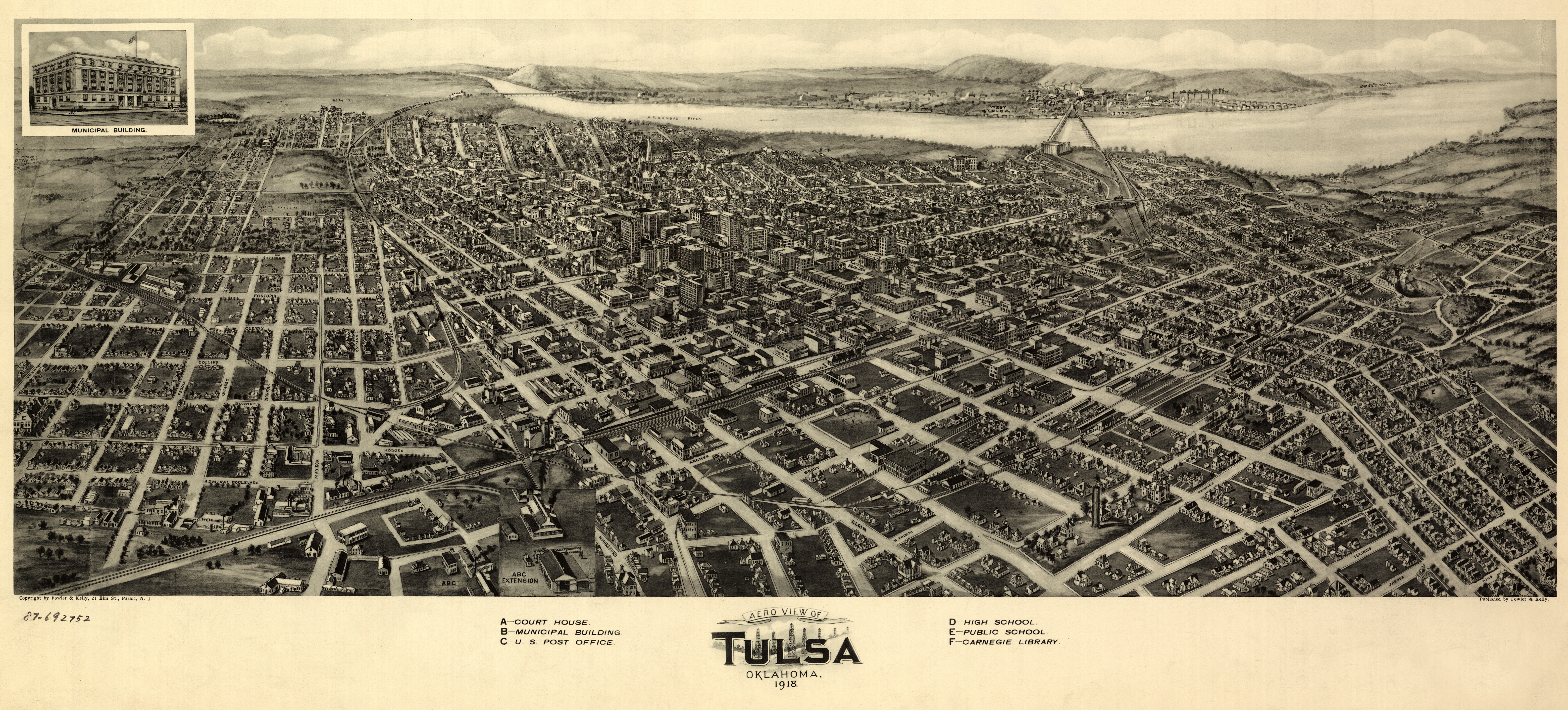

Artist Paul Rucker is creating a new multimedia work to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Tulsa Race Massacre. That’s when a thriving African American community was destroyed in a horrific act of violence that wiped out hundreds of Black-owned businesses and homes. Above, an aerial view of Tulsa, Okla., Fowler & Kelly, 1918.

CREDIT: GHI/Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

“Ten thousand Black people left homeless,” Rucker says. “Churches were burned. Schools. Libraries. Theaters. Everything in the Black community.”

Tulsa’s Greenwood area was a thriving commercial and residential district before the Tulsa Race Massacre, as its now known. Destruction of Black wealth and property – by arson, firebombing, even dynamite dropped from planes – went on for two days. The atrocity went unmentioned or was underplayed in official state history for decades. Police records, newspaper stories and other evidence from the era vanished from archives. It was only last year that the story became part of the curriculum in Oklahoma schools — after the HBO show Watchman helped bring it to the popular consciousness in 2019.

Its first episode begins with a shocking – and accurate – depiction of the mayhem. “A lot of people were giving Watchman a lot of credit for bringing attention to Black Wall Street,” Rucker says. “Well, people in the Black community have been talking about it for years.”

Rucker’s multimedia work tackles mass incarceration, lynching, police brutality and the various insidious ways America is shaped by our legacy of slavery. His 2018 TED talk, about appropriating the symbols of systemic racism, has almost two million views.

An art world powerhouse, Paul Rucker, who recently turned 53, can count seven museum shows this year. His resume reads like a list of prestigious grants and fellowships, and he was the first artist in residence at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. But before all the recognition and awards, Rucker worked as a janitor at the Seattle Art Museum. He used leftover art supplies to realize his vision, because he couldn’t afford new ones. Born in Anderson, S.C., Rucker’s father was a yard worker, born in 1905.

“He was 63 when I was born,” Rucker says. “He grew up during the height of lynching, so he was around during Black Wall Street. He didn’t tell me about the bad incidents that may have happened to him. But he had to be careful. He had to be careful about what direction he looked. You had people during the time he was born who were lynched because they knocked on the wrong door.”

Paul Rucker remembers seeing Klan rallies when he was small. As a young teen, he sat on the street and ate ice cream while watching a Klan parade go by. About seven years ago, Rucker started sewing Klan robes himself. “I use kente cloth. I use camouflage,” he explained in his TED talk. The material stands for the ways racism gets camouflaged, too. “We have segregated schools, neighborhoods, workplaces. And it’s not the people wearing hoods that are keeping these policies in place. My work is about the long-term impact of slavery. The stealth aspect of racism is part of its power. Racism has the power to hide. And when it hides, its kept safe, ’cause it blends in.”

Paul Rucker’s work will be featured in seven museum shows in 2021.

CREDIT: Ryan Stevenson/Paul Rucker

With his Tulsa project, originally called Banking While Black, Rucker first planned to build an installation using the guts of an old bank. But COVID-19 changed everything. Now the project is virtual, with three universities involved: George Washington University, Virginia Commonwealth University (where Rucker gave a recent talk about the project) and Arizona State University, which plans some sort of physical exhibit with the project this fall.

“Paul does ask us to bear witness, for sure,” says Miki Garcia, director of the ASU Art Museum. Her school’s partnering with Rucker, she says, in all kinds of ways this year, including a huge group project called Undoing Time: Art and the Histories of Incarceration. “He is surfacing histories that have been intentionally, I believe, obscured. So whether it is looking at the history of mass incarceration or the Klan robes or the Tulsa Race Massacre, he makes history viscerally present.”

In this project, the history focuses on three Black Wall Streets: in Tulsa, Durham, N.C., and Richmond, Va. A website, designed with the help of students and professor Kevin Patton at GWU’s Corcoran School of Art and Design, will immerse visitors into these communities at their zenith.

“We’re not including any of those pictures of destruction on this website,” Rucker says. “Zero. ”

While some Black communities, such as those in Tulsa and Rosewood, Fla., were savagely destroyed by mobs in the early 1920s, Rucker points to another kind of economic violence wrecked upon thriving Black commercial districts all over the county. Mid-century urban renewal programs prioritized highways over Black communities. They tore up Black neighborhoods and split them apart, in cities from Syracuse to Miami to Indianapolis to Houston to Oakland.

“A lot of my work is about violence,” Rucker says. “I mean, I have more work about dead people than anyone I know. It wears me down, but I have to tell these stories because they need to be told. [But] this may be my last project around race and dealing with atrocities.”

The legacy of these economic atrocities, says Rucker, include the chipping away of Black wealth, the coordinated exclusion of Black people from boards and management jobs, and from representation in classrooms. For the past year, Rucker acted as a mentor to a student group called B.A.S.E – Black Art Student Empowerment at Virginia Commonwealth University, and worked with them to develop a database of Black-owned businesses to include in the final project.”

“It’s important we have elevated into this culture and legacy that has been left behind,” says Shayne Herrera, the group’s president. A VCU senior, he’s concentrating on painting and printmaking. Too often, he’s the only African American in the room. “Paul met with us every week during the pandemic making sure that we can create this space of, you know, Black creativity and safeness.”

Ultimately, Rucker wants to enlist audiences in understanding a complicated and cruel history in order to move forward with compassion. Three Black Wall Streets, he says, is not just about something that happened 100 years ago. It’s about the ashes of destruction that smolder still.

“[Three Black Wall Streets] is also about student loans,” the artist says, and about owning real estate. People ask Rucker about his Klan robes all the time, he adds, admiring his ‘radical’ art work. “But the most radical thing I’ve done as a Black man — as an artist – is buy property.”

Rucker owns a house near the VCU campus, and what used to be Richmond, Virginia’s Black Wall Street, a place where the first Black woman became a bank president, in the early 1900s. Today, Rucker is one of only a couple of Black homeowners in the area. When the country’s Black Wall Streets were ravaged and ruined, he says, we were left with a moral and spiritual bankruptcy.