Ecologists help with burrowing owl ‘spring cleaning’ at Umatilla Chemical Depot

Listen

(Runtime 3:42)

Read

CORRECTION 4/10/25: An earlier version misstated how poisoning, trapping and shooting had affected burrowing owls numbers. The poisoning, trapping, and shooting of burrowing mammals like badgers, who create the burrows in which the owls live, has lowered their population numbers.

This time of year, biologists and technicians are doing some spring cleaning of their own at the site of the decommissioned Umatilla Chemical Depot in Oregon. They’re helping burrowing owls get their underground homes ready for the season.

An adult female burrowing owl receives a numbered leg band in a long-term research effort to better understand regional owl populations. Most of the owls nesting on the depot overwinter in California. (Courtesy: Department of Natural Resources / CTUIR)

The site is home to deer, songbirds and North America’s largest population of burrowing owls, said Jon Bloom, an environmental specialist with the Oregon National Guard and the Oregon Military Department.

“This base was so isolated for so long, there’s a lot of stuff out here that’s been able to be maintained without public disturbance,” Bloom said. “I love this bunchgrass, some of the native plant life and everything (that’s) been maintained.”

These burrowing owls can be persnickety about their homes. They decorate inside and outside, said Lindsay Chiono, a wildlife habitat ecologist with the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation.

“ (The decorations are) placed very precisely, apparently,” she said.

“ Yeah, and they’ll take things like corn, cob (and coyote scat),” Bloom said. “Their significant-other-to-be, they’ll see that stuff a while away and go, ‘Wow, that is fancy.’ I mean, that’s like the equivalency of like a fountain in your front yard.”

After cleaning, they put it all back — or else the owls will, Chiono said.

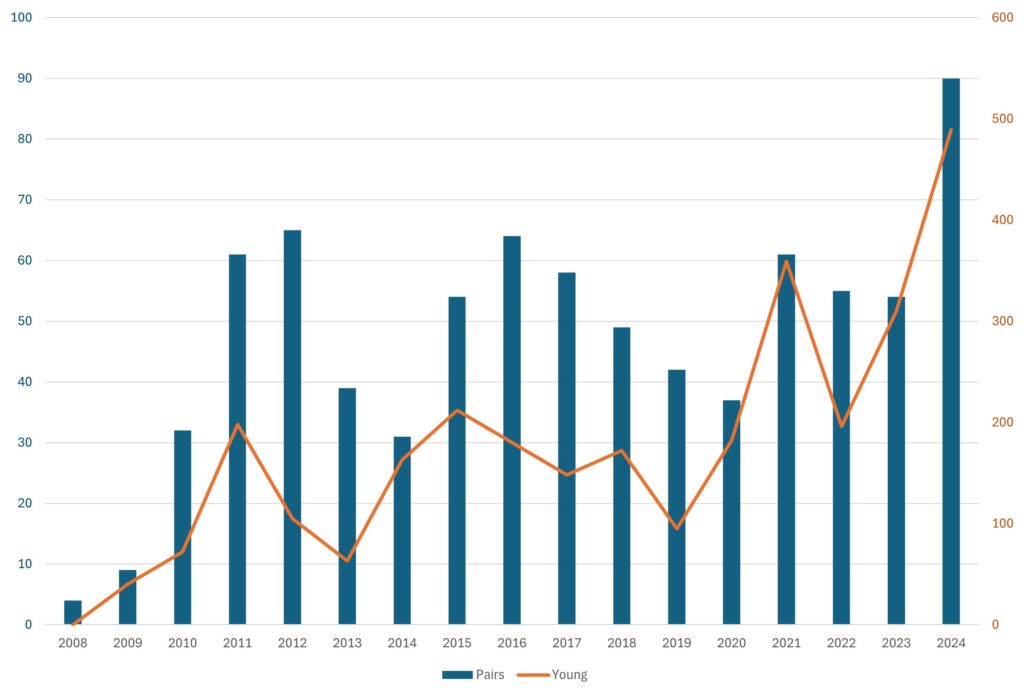

With the team’s help, the burrowing owl populations have soared.

In 2008, the owls had fallen to four nesting pairs on the entire site, she said. Last year, they counted nearly 82 pairs of breeding owls and 550 fledglings, Chiono said. A banner year.

“Every year we capture (and leg band) every adult owl that nests on the depot. And then we also capture all of the fledglings and put (numbered) bands on them so that we can track where they go from year to year,” Chiono said.

Most of the owls nesting on the depot overwinter in California. Last season, a couple of birds born at the site overwintered in western Oregon.

Burrowing owls in South America have also taught biologists new things, Bloom said.

“We’re learning things like they use different dialects over there than they do here,” he said.

The area of the depot they’re working at today is called Coyote Coulee. It’s a historic property of religious and cultural significance. This place is also a traditionally used travel corridor, hunting and traditional plant gathering area for the CTUIR.

It’s a place where the tribes have carried out their traditions and cultural practices important in maintaining their identity since time immemorial, said Teara Farrow Ferman, cultural resources protection program manager with the CTUIR.

Additionally, a portion of the northern Oregon Trail runs through the area.

“Everyone traveled through here,” Chiono said.

This graph shows the numbers of burrowing owl mating pairs and young born since the recovery project began at the site in 2008. Last year saw a record number of 82 pairs of breeding owls and 550 fledglings. (Courtesy: Department of Natural Resources / CTUIR and the Global Owl Project)

Even with a general upward trend in numbers, these birds still needed people’s help. Usually, they’d build their burrows out of old badger holes. However, the area is lacking in badgers, Chiono said. In 2023, CTUIR staff photographed a badger peering out of a burrow.

“ We don’t know if we have more than one,” she said.

A badger is pictured at the Umatilla Chemical Depot in this file photo. Burrowing owls nest in burrows dug by badgers, prairie dogs and other animals. Badgers disappeared from the site when the U.S. Army poisoned coyotes, which it believed were killing pronghorn calves.

(Courtesy: Department of Natural Resources / CTUIR)

That single badger created at least four natural burrows that owls nested in last year, Chiono said.

Badgers disappeared from the site when the U.S. Army poisoned and trapped coyotes, which it believed were killing pronghorn calves. Fencing prevented badgers from moving back onto the depot until 2023, Chiono said.

To help create spaces for the owls, biologists began installing artificial burrows across the site. David Johnson, founder of the Global Owl Project, expanded the network and improved the burrow design over time. There are now 180 burrows on the former depot, Chiono said.

“ The burrow chambers themselves are made out of Tree Top apple juice barrels,” she said.

Early on, they tried different colors. The owls hated white barrels.

“ When you look in the burrow chamber, it’s way too bright. It just seems wrong for the owls, it should be dark in there,” Chiono said.

Extra artificial nesting structures made from blue, repurposed Tree Top juice drums and 5-gallon buckets sit outside a concrete storage bunker. (Credit: Annie Warren / NWPB)

So now they use light-blocking blue barrels.

During the winter, the barrels get filled up with blowing sand, Chiono said.

“The tunnel will get clogged up and they won’t even be able to access the chamber,” she said.

“And then word spreads. At this location, we have slum landlords,” Bloom said, joking.

To clean out the sand, Chiono poked an 8-foot long PVC pipe with a grapefruit-sized ball made of car washing sponges. She pushed the plunger through the black tubes that serve as tunnels, moving the sand and debris into the owl’s main caverns, like living rooms.

The pair dug out above the burrows until they reached a pickle bucket that lifted out. That allowed them to see inside the burrow.

Lindsay Chiono examines the remains of a burrowing owl found March 24 in one of the artificial nesting structures at the site. The bird may have died from the cold, said Jon Bloom, left, of the Oregon Military Department, which partners with CTUIR on the recovery project. (Credit: Annie Warren / NWPB)

Sometimes, they find that nature has taken its course.

“Oh, there’s a dead owl,” Chiono said with a grimace. “ We’ll write down this band number so we know the fate of this poor bird.”

The owls don’t have a high survival rate from year to year, she said. They’re good prey for larger birds, like northern harriers.

Lindsay Chiono displays the leg band of a deceased burrowing owl. (Credit: Annie Warren / NWPB)

Poisoning, trapping and shooting of burrowing animals like badgers, who create the burrows in which the owls live, have also lowered population numbers. The owls’ rodent prey has seen a population decline, too. The biggest challenge, though, is conversion to agriculture, which has divided their habitat.

“The way I think about it is, owls evolved with predators like harriers and coyotes — it’s large-scale habitat loss that threatens the species,” Chiono said.

Federally, burrowing owls are considered a “bird of conservation need.” In Oregon, they’re listed as a “sensitive species,” and in Washington, they’re considered a “candidate species for listing.”

After cleaning things out, the pair dug weeds off the birds’ “front porches” by the tunnel entrances.

“We sort of do a little weeding and rough up the surface, so it looks like a badger has just dug it so they can recognize that there’s a burrow here,” Chiono said.

The team has around 10,000 acres to cover. Chiono has each burrow marked on a GPS map, all spread out. She spends a lot of time helping these birds.

“You can’t help but really care about them,” she said.

Jon Bloom, an environmental specialist with the Oregon Military Department and Oregon National Guard, adds a number to a stake marking an artificial nest location. A veteran, he said he finds peace in working with the burrowing owls. (Credit: Annie Warren / NWPB)

There’s still so much to learn about these birds. Because this population is so large, researchers have ample opportunities to ask and answer those questions.

“What do they like? What do they not like? Does it matter? Not matter? They’re interesting creatures,” Bloom said.

They said the research is just getting started.

As for the burrows, Chiono said, “Our hope for the future is that we won’t need to maintain this big network of artificial burrows because we’ll actually have the natural creators of those boroughs back on the site.”

A burrowing owl stands near its nest along a road leading to the concrete bunker, or “igloo,” where CTUIR staff store supplies for the burrowing owl recovery project at the former Umatilla Chemical Depot. (Credit: Annie Warren / NWPB)