What’s fuzzy, cute and sold out? Chicks

Listen

(Runtime 3:59)

Read

The first person showed up at 6:50 a.m., more than an hour before the store opened. The third person to arrive was Steve Irwin.

“You gotta get in line or get an early number,” Irwin said. “If you don’t, it’s over with. You might as well go home.”

By 7:45 a.m., a line of people had gathered outside the Tractor Supply Co. in Walla Walla. What were they waiting for? Baby chicks.

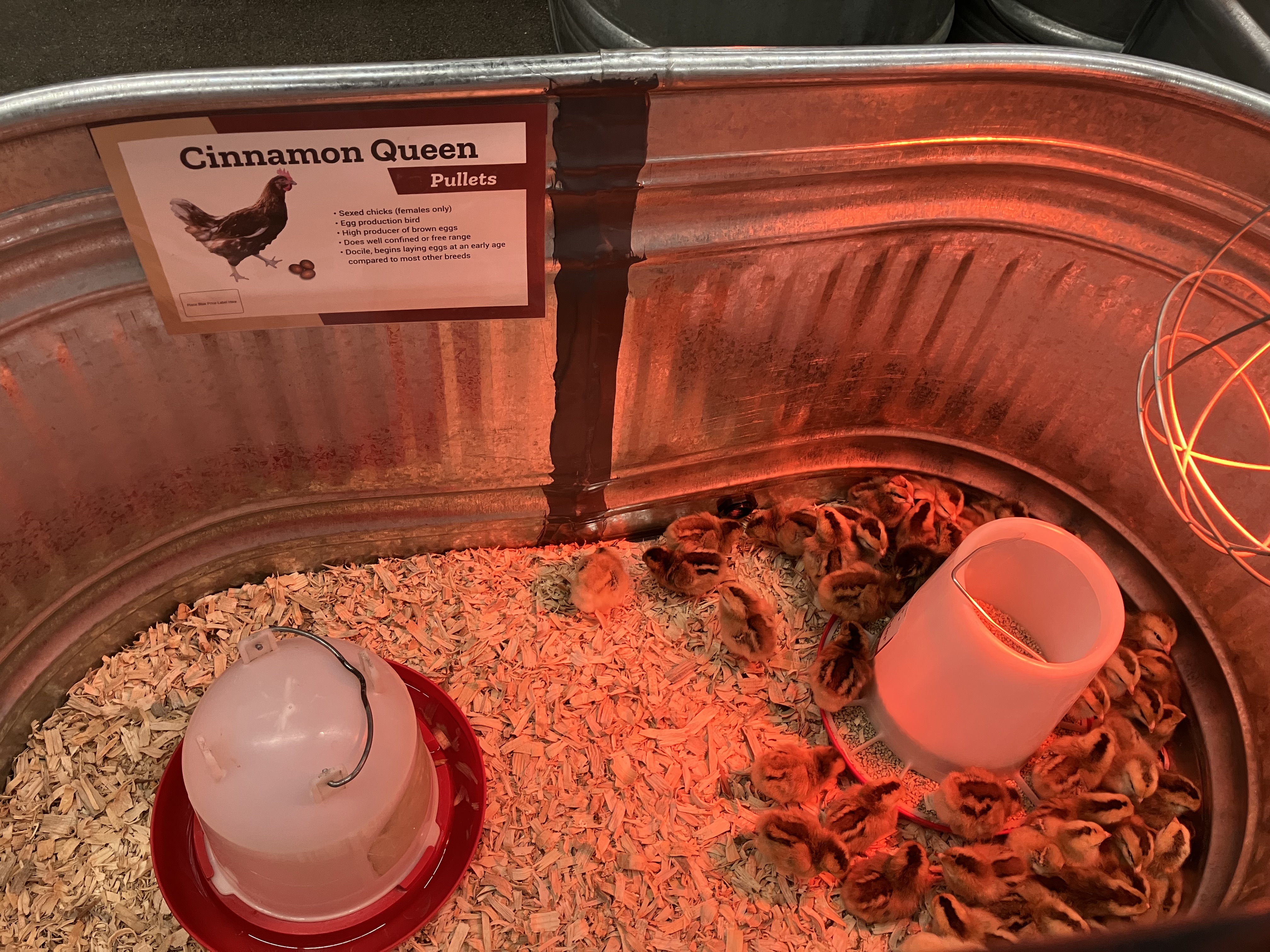

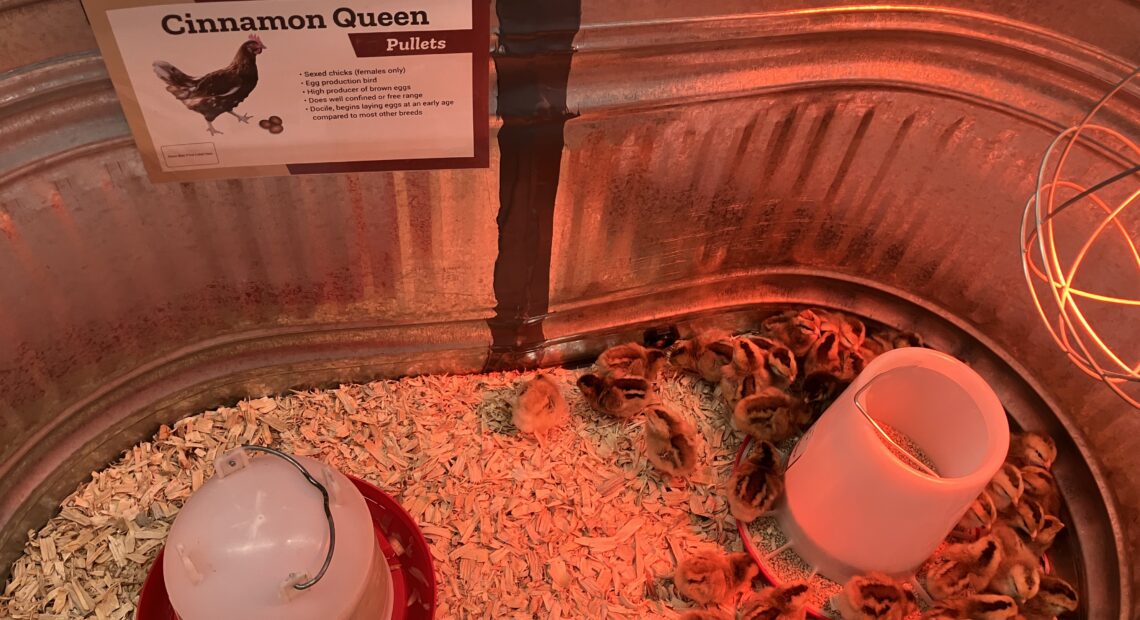

The birds, unaware of their celebrity status, huddled in silver tubs, basking under the red light of heat lamps. There were about 300 of them, all with delightful breed names like Cinnamon Queen, Isa Brown, Buff Orpington and Speckled Sussex.

As people filed in, store manager Tina Doerr stood at the doors, handing out laminated cards with a number and picture of a tiny baby chick. While the spring is always a popular time to buy chicks, she said this is the first time her store has used a numbered system. It’s how she’s been maintaining order when the crowds are double what they’ve been in years past.

“It has been craziness,” Doerr said. One customer cried when she didn’t get the birds she wanted; others have thrown their laminated cards at the cashiers for the same reason.

Customers wait at Walla Walla’s Tractor Supply store for their chance to purchase chicks. (Credit: Susan Shain / NWPB)

Chicks have been selling out quickly here. They’ll be gone in the span of 30 minutes, or an hour. That’s also been the case at other feed stores in the region — and across the country. The soaring price of eggs is the main explanation Doerr’s heard for the rush to buy chicks.

On average, the American Farm Bureau Federation says that bird flu has wiped out more than 10% of the country’s laying flock each year since 2022. That includes breeder hens and babies. That’s helped lead to a surge in egg prices — and a national shortage of chicks. Some online hatcheries say they’re sold out until fall.

Sarah Herrera and her daughter were fifth in line today. Herrera, who’s been raising chickens for a decade, has tried buying chicks from several feed stores with zero luck.

“I have never had this problem,” she said. “It’s insane.”

Herrera said it reminds her of the rush for toilet paper during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. And she’s worried that people are jumping on the chicken bandwagon who haven’t thought it through.

“We keep hearing from people, ‘Oh well, don’t you get eggs in like 12 weeks?’” Herrera said. “And it’s like, ‘No, this is a six-month thing.’”

Dr. Dana Dobbs, a veterinarian with the Washington State Department of Agriculture, also wants people to understand that chickens are a long-term investment.

“Chickens can live for many years, you know, 10 years or so,” she said. “It’s not just something you’re doing right now because of the price of eggs.”

Dobbs’ biggest worry, however, is bird flu. She hopes that people will take steps to protect their backyard flocks from the disease, as well as report any sick birds immediately. Since the start of the outbreak three years ago, the disease has killed more than 2.1 million birds in Washington and more than 168 million nationwide.

About 45 minutes after opening, the Tractor Supply store only had a handful of chicks left. All of the early bird customers left happy, carrying a chirping carton or two.

Fourteen-year-old Evelyn Hodgson arrived late, having already driven 30 minutes from her home in Athena, Oregon, to a store in Pendleton, only to find that it had already sold out. Then, her mom drove her another 45 minutes to Walla Walla.

Hodgson, who’d been looking for chicks for a while, wasn’t interested in the Andalusians or Bantams that remained. So she said she’d continue her quest for chicks, joking that her next step was going to be setting up a tent outside the store.