Getting out the vote, Northwest tribes say, is an ‘essential part of our civic duty’

Listen

(Runtime 3:52)

Read

Election officials and community leaders stepped on stage before bands played into the evening at a voter registration drive on Oct. 10 in Pendleton, Oregon. (Credit: Courtney Flatt / NWPB)

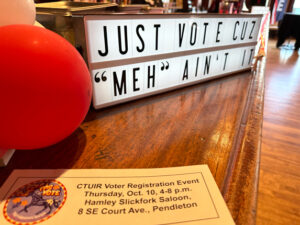

Towers of red, white and blue balloons frame the entrance to the Hamley Slickfork Saloon in downtown Pendleton, Oregon. A voter registration party hosted by the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation is just starting to kick off.

Bob Marley’s “Get Up, Stand Up” blares from speakers at the front of the room on Oct. 10. A few would-be voters stand in line near a computer to check their voter registration status.

“We’re hoping to get some younger folks here this evening,” said Corinne Sams, a member at large on the tribe’s board of trustees.

This public registration party was open to people with any viewpoint. The tribe hoped to register as many community members as possible.

Travis Snell, a public relations specialist with the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, helps community members check their voter registration status. (Credit: Courtney Flatt / NWPB)

In 2020, Native American votes helped secure President Joe Biden’s election. Native votes also tilted the election of U.S. Sen. Maria Cantwell, a Democrat, against incumbent Sen. Slade Gordon, a Republican, said Lisa Ganuelas, a member at large on the tribe’s board of trustees.

Politics has long been important to Ganuelas family. She said she remembered hearing about her grandmother educating Native voters in the 1940s.

Then, Ganuelas became the first legislative coordinator for the tribe. Voter education became even more important as she took on that role. She said she has many reasons for getting out the Native vote.

“There just goes another reason right there, my daughter, and then my granddaughter. So, standing up for their rights, too,” Ganuelas said.

In 1924, Congress passed the Snyder Act, also known as the Indian Citizenship Act. Before that, Native Americans had been denied citizenship – and couldn’t vote. Still, states put barriers in place to deny voting rights to Native Americans, according to the Native American Rights Fund.

“When you served your country, when you lost all your land to a country, when you lost so many percentage of your people to diseases in a country that was your homeland, then you’d better have a right to vote,” Ganuelas said.

The Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation’s voter registration drive on Oct. 10 in Pendleton, Oregon. (Credit: Courtney Flatt / NWPB)

Still, there have been lots of challenges to get the Native vote out, she said. For one, in 1998, tribal members had to drive a long way to get to a ballot box, Ganuelas said.

“We worked to get a ballot box on the reservation,” she said. “That first started at Mission Market. Later on, we moved it up to our governance center. At 8 p.m., our police department had to go bring (the ballot box) down to the Umatilla County Elections Department.”

Another challenge: Ganuelas said she’s talked to some tribal members who don’t want to vote in federal elections.

“They get kind of angry,” she said. “I think mindsets are kind of changing.”

That’s because the tribe is working with federal, state and local governments, she said. That shows people their votes mean something, Ganuelas said.

That’s something tribal groups in Washington are also hoping to convey. This year, the nonprofit environmental advocacy group Washington Conservation Action invested more than $1 million into its Native Vote Washington program.

“As a Native woman, I’m very interested also in building political power in tribal communities, right? I want people to be able to organize to get people who look like them from their communities on school boards, county commissions, city councils, all of that,” said Alyssa Macy, Washington Conservation Action CEO and a citizen of the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs in Oregon.

The Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation hosted a get out the vote event at Hamley Slickfork Saloon in Pendleton, Oregon. Once people registered to vote, they received stickers, T-shirts and tote bags. (Credit: Courtney Flatt / NWPB)

If people feel connected to an issue, especially locally, they are more likely to participate, she said.

Native Vote Washington has been knocking on doors on the Pullayup and Yakama Nation reservations. On the Yakama Nation reservation, there’s historically been low voter turnout, Macy said. A new district was also drawn after recent voting rights lawsuits.

“It is a majority-minority district right now. I think there’s some possibilities there, but folks have to start early. Get involved, get excited,” Macy said.

The group has also bought nonpartisan online ads, billboards and sent out thousands of mailers to everyone living on the reservation — whether people are members of a tribe or not.

Tribal voters could make a huge difference in the state, she said.

“Here in Washington state roughly 3% of the total population is Native and over the age of 18. In tight elections, that could really make a difference,” Macy said.

In Pendleton, Sams said, voting is “an essential part of our civic duty to recognize what we’ve fought for and how far we’ve come, and to ensure that we get our voices heard.”

For those who’ve never voted before, she said it’s a responsibility they must take seriously.

“It’s really our responsibility to determine how we want our government to function and who we want at the leadership level,” Sams said.

The work won’t end once election results are certified. Native get out the vote groups said they plan to organize year-round.