Billy’s magic: Tribal leader’s fierce fight for fishing rights to be honored with a statue in Washington, D.C.

Watch

Listen

(Runtime 13:31)

Read

When the sun-warmed blackberries are ready in late summer — so are the king salmon.

Daleena Sanchez, 7, picks blackberries in late summer on the banks of the Nisqually River at Franks Landing. Her great-grandfather, Dorian Sanchez, fished with his uncle, Billy Frank Jr.

(Credit: Annie Warren / NWPB)

So said Willie Frank III, the son of well-known Nisqually environmental and treaty rights advocate Billy Frank Jr. and grandson of Willie Frank Sr. He loves to catch salmon like his family and the Nisqually Indian Tribe has done since time immemorial. The former Nisqually Tribal Council chairman and longtime councilmember is now leading efforts to celebrate the life and legacy of his father.

“Anybody who knew my father, they felt that Billy magic. That Billy love,” Willie Frank III said. “The magic of my father was the magic of leadership. We’re all a piece of my dad.”

The youngest son of Billy Frank Jr., Willie Frank III, said he is passionate about lifting up the next generation of his community to learn, grow and heal together. “We have a voice, we have a seat now and we have to be ready to tell that story but also be ready to come up with that vision for the next seven generations,” he said. (Credit: Annie Warren / NWPB)

Billy Frank Jr. fought for decades to be able to fish salmon, a right reserved in Article III of the Medicine Creek Treaty of 1854 (10 Stat. 1132). Billy Frank Jr. struggled with addiction — he quit drinking in the 1970s — and death in his family. But he would still wake up with a smile to take on the world, Willie Frank III remembered.

“For most people, they’d wonder how my dad did it. And people would ask my mom, they’d say, ‘You know, what do you see? And Billy, he’s got such a different age gap than you,’ because they were quite a bit different in age. And she’d say, ‘He’s like this [Nisqually] River, the calmness of the river, you always know what you’re going to get. The river’s always going to be flowing. It’s going to be steady and calm.’”

Billy Frank Jr. kept fishing even when the state of Washington and police told him he could not. One of his first arrests was in the winter of 1945 at the age of 14, according to the book “Where the Salmon Run.” Billy Frank Jr. was arrested more than 50 times, Willie Frank III said. His father fought the state and its enforcement officers with other Native fishers and even movie stars like Marlon Brando. At the time, Washington was allowing massive catches by commercial outfits and sport fishers, according to the book “Messages from Frank’s Landing” by Charles Wilkinson. That meant that the Nisqually Indian Tribe and the other Northwest tribes would only get what was left. The tribes, and sometimes celebrities, would stage “fish-ins,” in which they would fish and get hauled off the river and jailed by law enforcement.

“It was nearly a daily event to get hassled by those guys,” said Billy Frank Jr. in the book “Messages from Frank’s Landing.” “It was a good day if you didn’t get arrested. After a while, I didn’t even bother to tell people at the Landing because they already knew: ‘If we don’t come back home, call C.J. Johnson.’ He was the bail bondsman.”

Larger than life

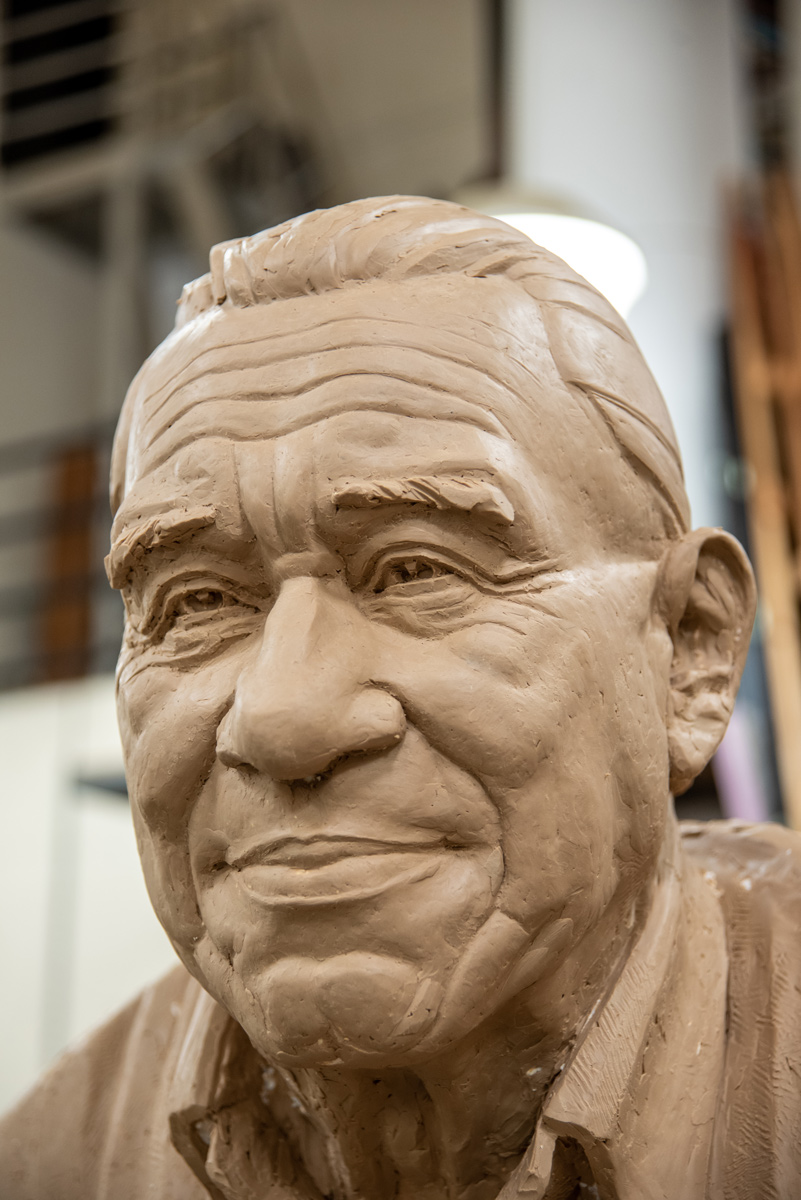

Now, in Olympia, there is a massive, nearly 11-foot tall statue and pedestal being molded out of Styrofoam and clay by well-known sculptor Haiying Wu in Billy Frank Jr.’s honor.

Artist Haiying Wu is assisted by his daughter, Cecelia Wu, 17, as he adds layers of clay to the Styrofoam model that will eventually be a bronze statue of Billy Frank Jr. in Wu’s temporary studio at South Puget Sound Community College. (Credit: Annie Warren / NWPB)

Wu learned as much as he could and collected photos from Billy Frank Jr.’s life in order to sculpt him. In some pictures, Billy Frank Jr. was fighting to fish or giving a public speech.

“But there’s sort of one picture, [a] black and white photo,” Wu said. “I saw him, which really strikes me, because in that picture he’s so calm. With this smile, with that calmness … he really shows that kind of how widely open his personality is and his forgiveness that he has.”

After being forged into bronze, the artist’s statue is set to be unveiled in Washington, D.C. in 2026. It is a collaborative project with of the Washington State Arts Commission, or ArtsWA, and the Nisqually Indian Tribe. In total, the project will cost more than $1.2 million. The statue will replace that of Marcus Whitman, a Protestant missionary who settled near present-day Walla Walla in the 1830s. The Whitman statue currently represents Washington in National Statuary Hall. Another identical Billy Frank Jr. statue will be placed in the Washington State Capitol in Olympia.

‘Don’t forget the water’

When the Puget Sound’s tide comes in, it pushes up the lower reaches of the Nisqually River. Where you think you should smell fresh water, the warmth of salt hits your nostrils amid the alder, hemlock, bigleaf maple and Douglas fir.

The tide is high on the banks of the Nisqually River at dusk at Franks Landing, a 6-acre community, just south of the Interstate 5 bridge near Lacey. The bend in the river, where the water slows, was historically an important gathering point and river crossing for tribes from around the region. It continues to be a popular fishing spot for tribal and non-tribal fishers alike.

(Credit: Annie Warren / NWPB)

The Nisqually people have an old creation story of how the Nisqually River came to run from təqʷuʔmaʔ, also known as Tahoma or Mount Rainier, to Puget Sound.

Nancy Shippentower is a Puyallup tribal member, lifelong activist and a niece of Billy Frank Jr. Her father, Don McCloud, was Billy Frank Jr.’s older brother. Shippentower’s parents were prominent fishing rights activists, contemporary with Billy Frank Jr.

Shippentower tells the old story this way: She says that Tahoma / Mount Rainier has a sister, Mount St. Helens. Mount Hood was the male. Then, Tahoma found out that Mount Hood was having an affair with St. Helens.

“She told her son she was leaving him now, she was leaving Mount Hood,” Shippentower recounts. “She told him, ‘Grab the water. Don’t forget the water,’” she said. “And he [Tahoma’s son] was so upset that when he grabbed the water, he stumbled and spilt the water and that’s how you got the Nisqually River. And, so, the Nisqually River is, to me, is sacred.”

Timeline of Billy Frank Jr.

Sources: Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission and Corey Larson, PhD.

The Nisqually Indian Tribe has always fished the Nisqually River and the Puget Sound.

After 2/3 of the Nisqually people are displaced to make room for Fort Lewis, Franks Landing is purchased by Willie Frank Sr. It is a 6-acre piece of private land on the Nisqually River.

At the age of 14, Billy Frank Jr. is arrested for the first time for salmon fishing.

Billy Frank Jr. serves in the U.S. Marines for two years.

The Washington Department of Fish and Game, now the Washington State Department of Fish & Wildlife, establishes rules to stop net fishing in off-reservation rivers.

Tribal fishers organize “fish-ins” to protest the curtailment of their treaty rights.

The federal government sues Washington state on behalf of the tribes.

Boldt Decision upholds tribes’ rights to fish in usual and accustomed places and to harvest 50% of salmon, steelhead and other fish in those areas.

Creation of Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission. This helps Northwest tribes speak with a single voice to manage and protect resources.

Billy Frank Jr. becomes the chair of Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission.

The Nisqually Indian Tribe opens the Kalama Creek Fish Hatchery on the Nisqually River.

Negotiations begin with Canada for the initial Pacific Salmon Treaty.

Billy Frank Jr. addresses President Bill Clinton at the Northwest Forest Conference in Portland, Oregon.

Billy Frank Jr. becomes founding board member of Salmon Defense.

President Barack Obama posthumously awards Billy Frank Junior the Presidential Medal of Freedom award.

Washington state Gov. Jay Inslee signs a bill authorizing the replacement of the Marcus Whitman statue with a new statue of Billy Frank Jr. at National Statuary Hall.

The struggle and Boldt

Billy Frank Jr. did not know how long his fight would be when he was in it. He just knew he wanted to keep fishing and that he should be able to given his treaty rights, and that his people had always fished, said his son, Willie Frank III.

Nancy Shippentower is a Puyallup elder, activist and a niece of Billy Frank Jr. She is pictured at Franks Landing where, as a child, she witnessed her family members beaten and arrested for exercising their fishing treaty rights during the “Fish Wars.” (Credit: Annie Warren / NWPB)

Nancy Shippentower remembered being a small girl at Franks Landing, a 6-acre piece of private land purchased by Willie Frank Sr., on the Nisqually River during that same time.

“We went through hell down here,” Shippentower said. “We had to deal with racism at school because all our teachers were sportsmen. So, what, they blamed us for taking all the fish? We did not.”

Shippentower remembered her mother taking her to see her father in jail.

“We didn’t have clothes like anyone else,” Shippentower said. “My mom was going to go buy me a pair of cheap shoes when I went and seen my dad, I burst out crying. I couldn’t touch my dad or nothing. I cried and cried. It was a heartbreaking time.”

Tobin “Sugar” Frank, Billy Frank Jr.’s eldest son, said the game wardens would arrest any Native American fishing in the Nisqually River.

“All my uncles and my dad were all in jail,” Tobin “Sugar” Frank said. “So, it left my auntie Maiselle [Bridges] and my mom just set net. And they got, they were up at the trestle setting net. And the game wardens come in, we filmed it and all. That was in [the movie] ‘As Long As The Rivers Run.’ Yeah, and then they arrested mom and my auntie right there. They wouldn’t let go of the net, so they pulled the net and grabbed them and pulled them over the boat … But yeah, that was a struggle when I was a kid to watch all that.”

Nisqually elder Tobin “Sugar” Frank, 63, is the oldest son of Billy Frank Jr. A lifelong fisherman, Frank remembered fishing with his father from a young age and seeing his family members get arrested during the “Fish Wars” in the 1960s and 70s. (Credit: Annie Warren / NWPB)

In 1974, after years of Native-led protests, fish-ins, arrests and several key fishing rights court cases, Judge George Boldt reaffirmed Washington tribes’ treaty rights to fish in “usual and accustomed” areas. The Boldt Decision was also powerful in that it defined “in common with,” that Native Americans reserved the right to 50% of the total fish harvest in those areas. At the time of the Boldt Decision, tribal fishers said they were getting just a fraction of that.

For years after, it was tense getting non-Native fishers to adhere to the new rules. There were rebellious counterprotests against the Boldt decision. About five years later, the Boldt decision was upheld by the Supreme Court which refused to hear the case.

I don’t believe in magic. I believe in the sun and the stars, the water, the tides, the floods, the owls, the hawks flying, the river running, the wind talking. They’re measurements. They tell us how healthy things are. How healthy we are. Because we and they are the same. That’s what I believe in.

Billy Frank Jr., “Messages from Frank’s Landing”

For its part, the Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife said Billy Frank Jr. made it his life’s work to advocate for Indigenous people and to protect the fish, waterways, wildlife and lands of the Pacific Northwest.

“We share in his commitment to advance conservation for fish and wildlife and continue to walk in his legacy for caring for this state’s natural resources,” said Kelly Susewind, director of WDFW.

Late summer on the Nisqually

On the Nisqually on a late August day, the river is the color of a deep emerald.

Its brackish waters churn under the 40-horsepower outboard motor of Willie Frank III’s aluminum boat, spewing up a white froth behind him.

In a Pala Braves tank top jersey with black and white eagle feathers on the side, Willie Frank III deployed gill nets across stretches of the river at designated places, called sets, that have been passed down through his family for generations. Family members, including his older brother, Tobin “Sugar” Frank, and friends helped each other set nets. It is a delicate and practiced maneuver not to topple out of the boat.

After pulling up the few first king salmon, Willie Frank III hoops and hollers.

Even though he is all smiles and laughter on the water, catching the salmon for his family and his tribe is serious business.

Elizabeth Van Tiem and Tobin “Sugar” Frank haul in their first catch of the day at Franks Landing on the Nisqually River during the summer chinook salmon run. Van Tiem, a youth coordinator for the Nisqually Indian Tribe, is one of the few female Nisqually tribal fishers. “I’m able to feed my community, my family, my friends, my relations,” she says. “That makes you feel Indian.” (Credit: Annie Warren / NWPB)

One or two days now

Now, many of the fish that used to come back to the Nisqually River don’t arrive anymore.

Willie Frank III and others say some of the challenges are: massive fishing operations at sea near Alaska, pollution, invasive predators, sport anglers and climate change.

An enrolled member of the Northern Arapaho Tribe, Peggen Frank is the executive director of Salmon Defense and wife of Willie Frank III. She works to protect salmon, which she calls an “amazing species.” (Credit: Annie Warren / NWPB)

Peggen Frank is the executive director of the Olympia-based nonprofit Salmon Defense and is Willie Frank III’s wife. She said Billy Frank Jr. paved a great path and that Native leaders now have to keep fighting for salmon.

“Having Billy at the Statuary Hall and having him at our capitol, let’s really start to make progress on the things and the policies that he was trying to affect for the last 30 years, like riparian buffer systems along our streams and our rivers,” Peggen Frank said. “Just basic, basic things that would enhance and protect our environment by utilizing the treaty rights, by listening to the tribes, by accepting and implementing tribal solutions, because we are the stewards of the land.”

She added to the list of challenges for Washington salmon with increasing pressure from things like climate change, dust from vehicle tires, salmon-munching sea lions, the state’s growing population and watershed destruction.

“So, there’s things that we can do,” Peggen Frank said. “We can start to connect to our ecosystems … learning where your watershed is connecting to it … So, we need to help our Mother Earth just as she helps us.”

Willie Frank III said Nisqually fishers used to fish seven months out of the year. That is no longer the case.

“We have a generation who’s not even going to grow up having that opportunity to fish,” Willie Frank III said. “And I’m very fortunate. I feel like I’m kind of part of that last generation of the good fishing days, you know?”

Catching one to two five-by-four-feet deep totes of fish every day was common as recently as the mid-2000s. Now, Native fishers said they are lucky to catch several fish on an open day on the Nisqually. Many of the fish that are caught come from the tribe’s hatcheries, said Debbie Preston, director of communications for the Nisqually Indian Tribe.

Not sitting still

Billy Frank Jr. is not sitting still.

He died at 83 on May 5, 2014, but he’ll forever be depicted in the National Statuary Hall with a smile.

“Well, it would have been easy to be bitter,” Nancy Shippentower said about Billy Frank Jr.’s life. “It would have been easy to be hateful. But that gets you nowhere. You always have to be positive. You always have to say, ‘This is a good day. It’s a good day.’”

The new statue of Billy Frank Jr., sculpted by artist Haiying Wu, will be one of just a few in National Statuary Hall depicted with a smile. (Credit: Annie Warren / NWPB)

One of Willie Frank III’s fondest memories of his father is something very human — Billy Frank Jr.’s sweet tooth and his weakness for salty meats.

“Bacon and eggs and, you know, sausage, Spam,” Willie Frank III said. “He loved Spam and he’d always sneak it. … And so, as he got older, you know, like after he passed, I had to go through all of his stuff, you know. Here I’d find candy bars hidden in his room … It was hard to tell my dad no on the bacon and eggs.”

Billy Frank Jr.’s public legacy is still alive with the maintained rights to fish through the Boldt Decision and the Medicine Creek Treaty of 1854.

Posthumously, he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in November 2015.

His spirit is alive too, Willie Frank III said, in the laughter and camaraderie of the fishers on the emerald-hued waters of the Nisqually River.

“My wife [Peggen Frank] always gets those, you know, Facebook flashbacks of like 2007 and 2008 when we used to have good fishing seasons and we’d have three or four totes of fish we’d catch in the day,” Willie Frank III said. “And it was always cool because my dad, you know, that’s what he loved to see. He loved to see those fish coming in.”

The sun sets at Franks Landing, where descendants of Billy Frank Jr. continue to fish as their ancestors have done since time immemorial. (Credit: Annie Warren / NWPB)