Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Conclave

“Without uncertainty, there is no doubt. Without doubt, there is no mystery. Without mystery, there is no faith.”

Let’s face it. Without an intelligent script, talented actors and thoughtful direction, Conclave would not be such an involving thriller. This new godsend of a film from Edward Berger (the Academy Award-winning All Quiet on the Western Front) embraces the ambition and hypocrisy of its characters in the manner of Hollywood’s Golden Age. Think 12 Angry Men, multiplied by nine, ecclesiastical style.

Based on the best-selling novel by British author Robert Harris, the movie plays out in compressed time and space. The self-effacing and doubt-afflicted Cardinal Lawrence (Ralph Fiennes, in an exquisitely calibrated performance) has inherited the daunting task of presiding over a gathering of his fellow cardinals, as they attempt to choose a new pope to succeed his friend. The recently deceased pontiff has gone to his final resting place with several enticing secrets.

Once the College of Cardinals has assembled to conduct one of the Catholic Church’s oldest rituals, the Vatican goes into lockdown. Windows are shuttered. Doors are secured. A shroud of secrecy descends.

Almost immediately, we begin to witness the fault lines in the senior hierarchy. The cardinals seat themselves in cliques at the dining room tables, grouped according to language, geography and philosophy. They tally each round of votes religiously, and they confront and cajole each other in hallways and private quarters. It turns out that God and politics both work in mysterious ways.

Lawrence favors his “progressive” colleague Bellini (Stanley Tucci), even as three other contenders emerge: Tremblay (John Lithgow), Tedesco (Sergio Castellitto) and Adeyemi (Lucian Msamati). Each has baggage. Each has liabilities. Each suspects Lawrence of having his own aspirations for the papacy, however strongly denied. Tedesco, with his blunt assertions about race, language, marriage, immigration and terrorism, echoes the broader, secular debates outside of the Church. Ultimately, a “wild card” appears to offer a more nuanced, realistic perspective.

Enter another character with a pivotal role to play. Sister Agnes, sublimely portrayed by Isabella Rossellini, leads the nuns assigned to facilitate the conclave by cooking and cleaning. Even though her character remains speechless for the first act of the movie, you know that she has knowledge of all kinds of dirty laundry.

Screenwriter Peter Straughan (an Oscar nominee for Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy) cleverly structures the script and parses out the dialogue in a way that lends constant momentum to the story. The facade of religious faith and devotion is peeled back, one revelation at a time. The shifting alliances and expectations become more urgent with each ballot and each puff of black smoke, the traditional symbol of an inconclusive vote.

Director Edward Berger deftly manages the large cast and confined spaces. The dormitory area is shaped like a cross. The Sistine Chapel is dominated by its richly painted ceiling, replete with Michelangelo’s Creation of the World, God’s Relationship with Mankind, and Mankind’s Fall from Grace. The courtyard is a setting of emancipation–a place to enjoy a different kind of puff, with the cigarette butts as the evidence. (Principal photography took place at Cinecitta Studios in Rome, the “Hollywood of Italy.”)

The very busy, Oscar-winning German composer Volker Bertelmann (Lion, All Quiet on the Western Front) has accomplished his own minor miracle here. He employs a single theme–suggestive and tense–to maximum effect, constantly transforming it to anticipate and enhance plot developments, without overpowering the action. He also emulates the likes of John Williams by composing a separate mini-suite for the closing credits.

Just like the novelist, Robert Harris, director Berger and screenwriter Straughan build this traditional, classic suspense tale to a deeply ironic climax. The venue and story suggest austerity; the execution betrays richness and imagination. Humor, too, as exemplified by a curtsy and a coffee maker. The foundations of the Catholic Church are rocked in more ways than one during this Conclave, but the film is a solid entertainment. We have a winner. Cue the white smoke.

Related Stories:

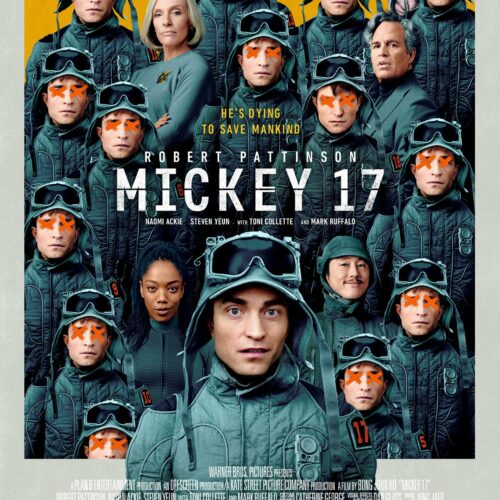

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Mickey 17

Movie poster of Mickey 17 courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures. Read “You don’t look like you’re printed out. You’re just a person.” In writer-director Bong Joon Ho’s new science fiction

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: A Complete Unknown

In director James Mangold’s new film, Timothée Chalamet portrays the young Bob Dylan (the professional name he adopted at age 21) from 1961-1965. He gives a remarkably nuanced, accomplished performance in a movie that occasionally gets bogged down in truncated or unnecessary scenes, but not too often. The supporting cast shines as well.

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Nosferatu

A classic tale laced with horrific, religious, folkloric and erotic themes. Robert Eggers seemed destined to make a movie about it. Finally, after a decade of preparation, he has.