Advocates: ‘If you’re standing outside a prison wall, you have the right to vote’

Listen

(Runtime 4:07)

Read

Editor’s Note: If you or someone you know is struggling with mental wellness, you can always call the national Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 988.

It’s been almost three years since a new Washington state law restored voting rights to people who’ve been convicted of a felony and are out of prison. However, it’s been difficult to get people to vote. Now, advocates are hoping they can get people to register before the election.

“Literally, if you’re standing outside a prison wall, you have the right to vote,” said Kelly Olson, a member of the Free the Vote Washington coalition. Olson was formerly incarcerated.

However, sometimes it’s not that simple, she said. Voting can feel like a privilege once you leave prison.

When Latrice Williams was released from prison in 2014, she had a lot on her mind.

She needed housing. She needed a job. She needed to get her kids back. The world had changed over the seven years of time she’d served.

“Sinks turning on by themselves. Yeah, I don’t know, man,” she laughed, remembering all the changes.

She’d changed as well. But she said there wasn’t a roadmap to reintegrate into society. After struggling to find her place, Williams said she was headed to Spokane’s 125-foot-tall Maple Street Bridge, on the verge of ending it all.

Voting rights were the last thing on her mind.

First, she had to survive.

“Once somebody has stable housing, once somebody has a job, once somebody has reliable transportation. Then, you can come to me and say, ‘OK, now I’m ready to learn how to vote.’ You’ve got to have the bare necessities first,” said Virla Spencer, the CEO of The Way to Justice in Spokane.

The Way to Justice is a nonprofit law firm that helps people who’ve been harmed by the justice system.

In 2022, a Washington state law automatically restored voting rights to people convicted of felonies the moment they left prison. However, there’s so much more that people need, Spencer said.

She said that’s very likely why few people with convictions haven’t voted in high numbers yet.

A future voter sticker at a 2024 voter registration drive. Now, anyone with past felony convictions can register to vote in Washington. (Credit: Courtney Flatt / NWPB)

“When you get out, this is the power that you have in your hands,” Spencer said, “But if you don’t educate people on what that means, sure, when they come out they’re thinking about survival mode. It sure as hell’s not standing in line to check the ballot box.”

Now, organizations across the state, including The Way to Justice, are working to teach people about their voting rights.

“There was so much work, and the foundation was laid, and so many people lost their lives for people to have the right to vote. So, we have to encourage people to keep on voting,” Spencer said.

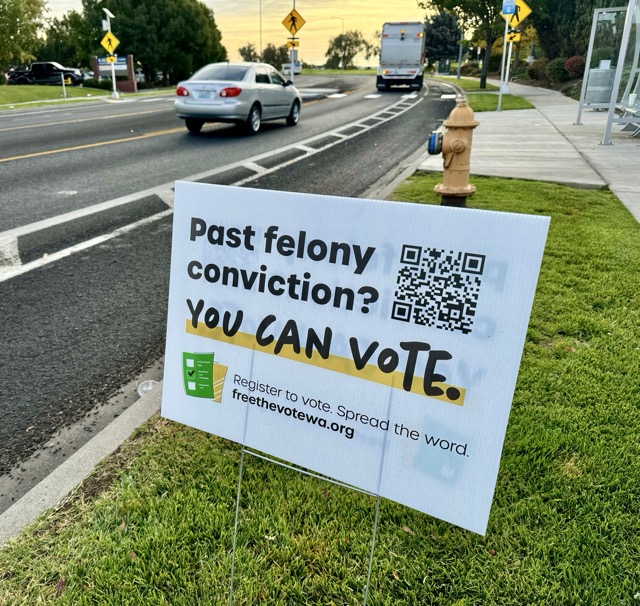

To help with that encouragement, Free the Vote Washington signs in the Tri-Cities line busy streets and are posted next to bus stops, letting people know they can vote if they have a past conviction.

The history of voter disenfranchisement is rooted in racism, said Olson, who’s also the policy manager at the nonprofit Civil Survival, which helps people in Washington who’ve been impacted by the criminal legal system.

“There never has been any public threat other than the threat to people who are in positions of power,” Olson said.

She said studies show people who are civically engaged have lower recidivism rates.

“They feel like they’re part of their society, part of their community, and that their voice matters,” she said.

The Washington State Department of Corrections now gives people voting pamphlets as they leave prison. Olson, who was released in 2007, said it was a little scary to vote before the law. All the restrictions were confusing. Getting your voting rights back felt complicated.

“It used to be that you had to pay all of your legal financial obligations before you could vote. And then it was you needed to be making payments on it,” she said.

Now, 23 states restore people’s voting rights post-incarceration, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. However, not all states automatically reregister people to vote, including Washington.

The last day for online voter registration in Washington is Oct. 28. People can still register in person on Election Day.

Since the law went into effect, voting rights have been restored to around 23,000 people with past felony convictions, said Chris Wright, communications director for the Washington State Department of Corrections.

In Washington state, voters can turn in ballots to a drop box. Advocates said voter registration drives and educational information have helped more people with past felony convictions register in Washington this year. (Credit: Cindy Shebley / Flickr Creative Commons)

People’s voices, Olson said, have power.

But after coming out of prison, Williams said it felt like she lost her citizenship, even after serving her time.

Everything was stripped away from her, she said.

“When I got home, I’m like, ‘Damn, I’m serving a sentence all over again,’” Williams said.

“Just because you’re in prison or been in jail doesn’t mean that you’re a bad person,” Spencer responded.

Williams said she wished there were more programs to teach people about restoring voting rights while people were incarcerated. That way, they’d have a better understanding when they left, she said.

Perhaps, Spencer said, beyond handing people a pamphlet, they could fill out voter registration cards as they exit the building.

“‘Here’s a card, fill it out, we’ll mail it for you.’ So that way you’re catching everybody at the gate,” Spencer said, “In fact, if you’re inside, and you’re teaching all these classes to folks that are just about to get out, why not teach that class? Why not empower people?”

That could be one step off their plates while they figure everything else out, Spencer said.

“When people don’t turn out to vote, it’s because they’ve experienced some kind of trauma. Something happened. Why do you feel like you don’t have any power?” she said.

She said she wants to see formerly incarcerated people and young people take a stand and organize to get their voices heard, to empower themselves.

“We’ve been fighting our whole lives,” Spencer said.

“We’ve been fighting our whole lives,” Williams agreed.

“And that’s what we have to do, we have to keep fighting,” Spencer said.a