Asotin County assessment shows needs in mental health, housing, substance use treatment

Listen

(Runtime 1:27)

Read

An assessment by Asotin County Health District shows that mental health, housing and aging in place, along with substance use, are some of the largest health issues facing the community.

The assessment, which received over 700 responses from community members living in Asotin County, also included community leader interviews and focus groups covering substance use, mental health, housing access, aging in place and open topic health needs.

Mental health was the biggest health issue raised by community members. In Asotin County, 24% of adults reported poor physical or mental health keeping them from completing usual activities, compared to 11% statewide.

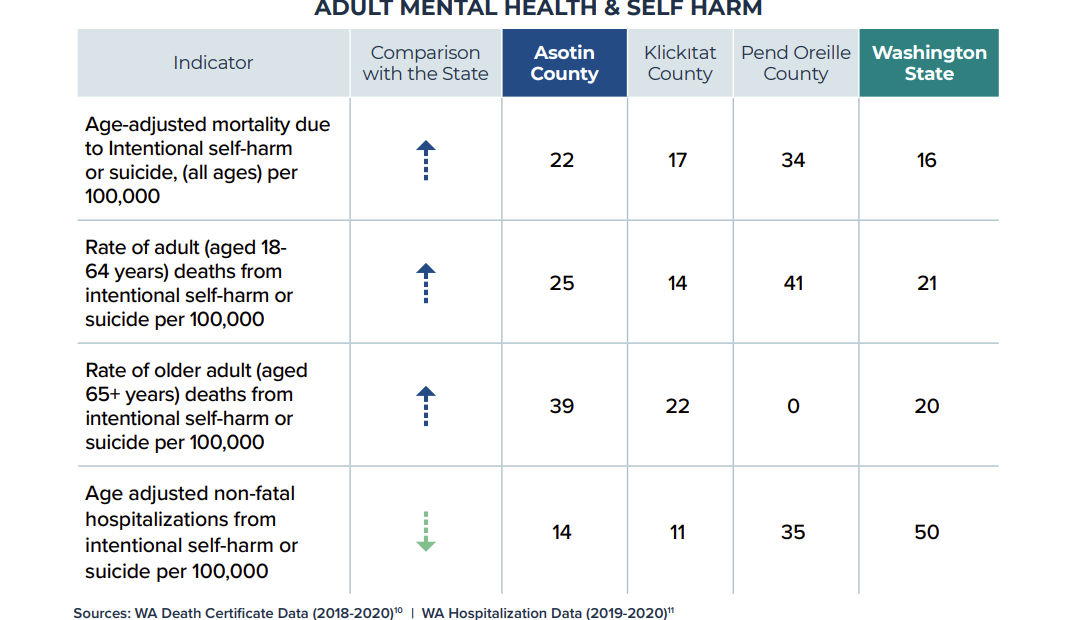

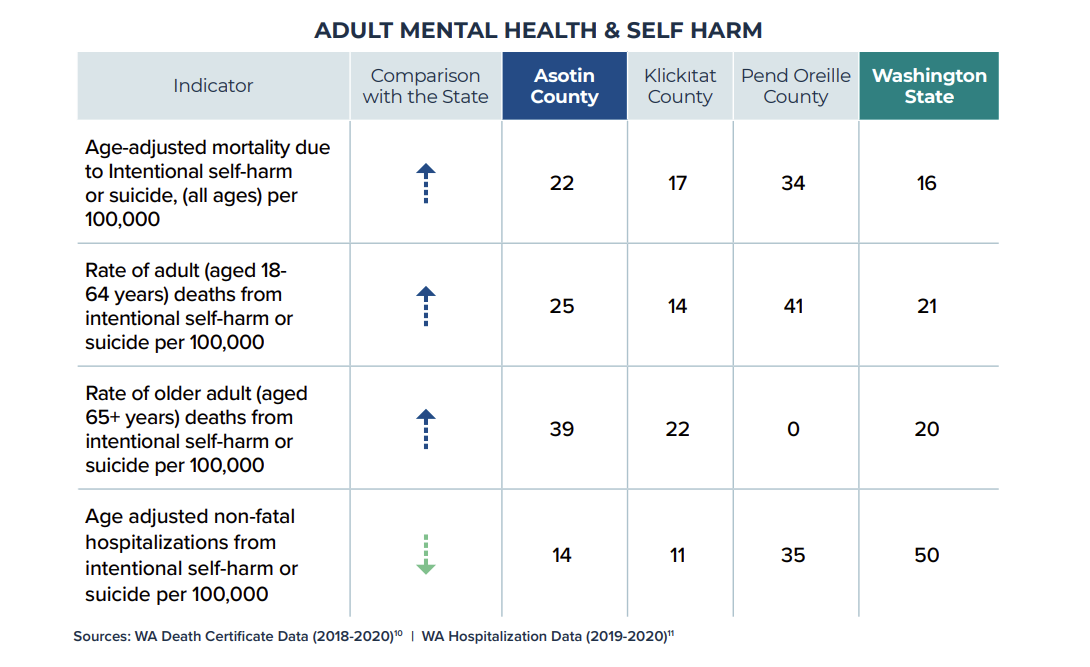

The county also had an age-adjusted mortality rate due to intentional self-harm or suicide of 22 per 100,000, compared to the state average of 16 per 100,000.

Adults weren’t the only ones struggling with mental health over the past few years. The assessment included information from Washington’s 2021 Healthy Youth Survey, which showed a higher than state average of eighth grade students who had seriously contemplated or attempted suicide in the past 12 months.

Lora Gittins, a community health program manager with the county, said youth mental health today is even worse than what the 2021 survey shows.

“Those numbers increased in 2023,” she said. “It’s really heartbreaking.”

The health district is aiming to add staff in the future, Gittins said, including a prevention specialist who would work in substance use, overdose and suicide prevention.

A major health goal for the community is combatting the stigma of talking about issues like suicide and substance use, she said.

“Just because you’re talking about it doesn’t mean it’s going to put it into your kid’s head, or that you’re going to cause someone to think more about suicide or more about using,” she said. “That’s the key to prevention, is collaboration, community-building and connection.”

Several community members noted that only one nearby provider, Quality Behavioral Health, accepts Washington Medicaid, and that often the only option to be seen quickly is through the emergency room for people in crisis.

“They do absolutely everything they can, but they don’t have enough,” said Skate Pierce, a business owner and Clarkston city councilor. He is also a Board of Health chairperson. “So, if you need care, if you need urgent care, you have to (get there) at seven in the morning, and just hope that somebody can see you.”

Asotin County residents identified housing as the second-biggest health need within the community.

In Asotin County, the median property value was $229,300 in 2021, and the median household income was $57,263. Over 70% of residents owned a home, and 67% had a mortgage.

Compared to the Washington state average, the county had a lower percentage of residents who spent more than 50% of their household income on housing.

The county also had a lower percentage than the state average of residents with a mortgage who spent more than 35% of their income on housing.

However, Gittins said, many respondents said there was still too big a gap between accessible, affordable housing and the needs of the community.

“By state standards, we have fairly decent housing prices,” she said. “But we know from living in this community that there are still needs to be met.”

Several focus group attendees and community leaders pointed to the fact that many families end up without stable housing even if they have a roof over their heads.

“We have a number of students and families that are considered homeless because they’re couch-surfing, living with relatives, staying at the youth center or being housed in hotels,” said Donna Franklin, director of health services at the Clarkston School District. “Families that struggle with addiction, violence or legal issues often have even more challenges in finding stable shelter.”

According to the Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction, 3.5% of children in Asotin public schools were homeless in the 2022-2023 school year, compared to 2.8% statewide.

County residents also expressed concerns over the growing senior population and their ability to continue living in their homes.

In Asotin County, about a third of residents are over the age of 60, and 17% are over the age of 70. Of seniors 65 and older, nearly half earn more than the federal poverty level, but less than the basic cost of living for seniors in the county.

Of the survey respondents, 23% chose to write about substance abuse being the most important issue facing the county.

A rolling count from 2020 to 2022 showed a decrease in nonfatal opioid hospitalizations, but a steady increase in opioid deaths. Respondents repeatedly noted a lack of inpatient and outpatient substance use treatment options as a major concern.

Overall, community members identified five top barriers to meeting health needs.

These included a lack of health care providers; a lack of health insurance coverage and insufficient or inconsistent coverage for specific needs like dental or mental health services; prejudice and stigma; cost or financial barriers; and a lack of collaboration between health care and social service organizations and service access.

The report identified several goals for the county to help meet health needs identified in the survey. They included developing a senior resource guide, which is now available through the district’s website, and a Community Health Improvement Plan slated to begin this fall.

Other goals included increasing awareness and education about safer storage of prescription drugs and increasing naloxone availability. The report also highlighted the goal of relocating the health district’s office to Clarkston, and growing staff in order to increase programs and outreach.