Study shows short pesticide exposure harms fish

Listen

(Runtime 0:60)

Read

Although pesticides can rid your home of cockroaches or farm fields of unwanted insects, they also can harm fish and potentially even people, according to a new study from Oregon State University.

At high concentrations, these commonly used pyrethroid pesticides, bifenthrin, cyfluthrin and cyhalothrin, act as a neurotoxin for pests.

“You’re basically doing an uncontrolled experiment when you spray chemicals like this in your house. It affects other things besides insects,” said Susanne Brander, the study’s co-author and an associate professor at OSU’s Hatfield Marine Science Center.

At low concentrations, the pyrethroid pesticides disrupt fish’s endocrine system, which produces hormones. The scientists wanted to better understand how short of an exposure would harm fish.

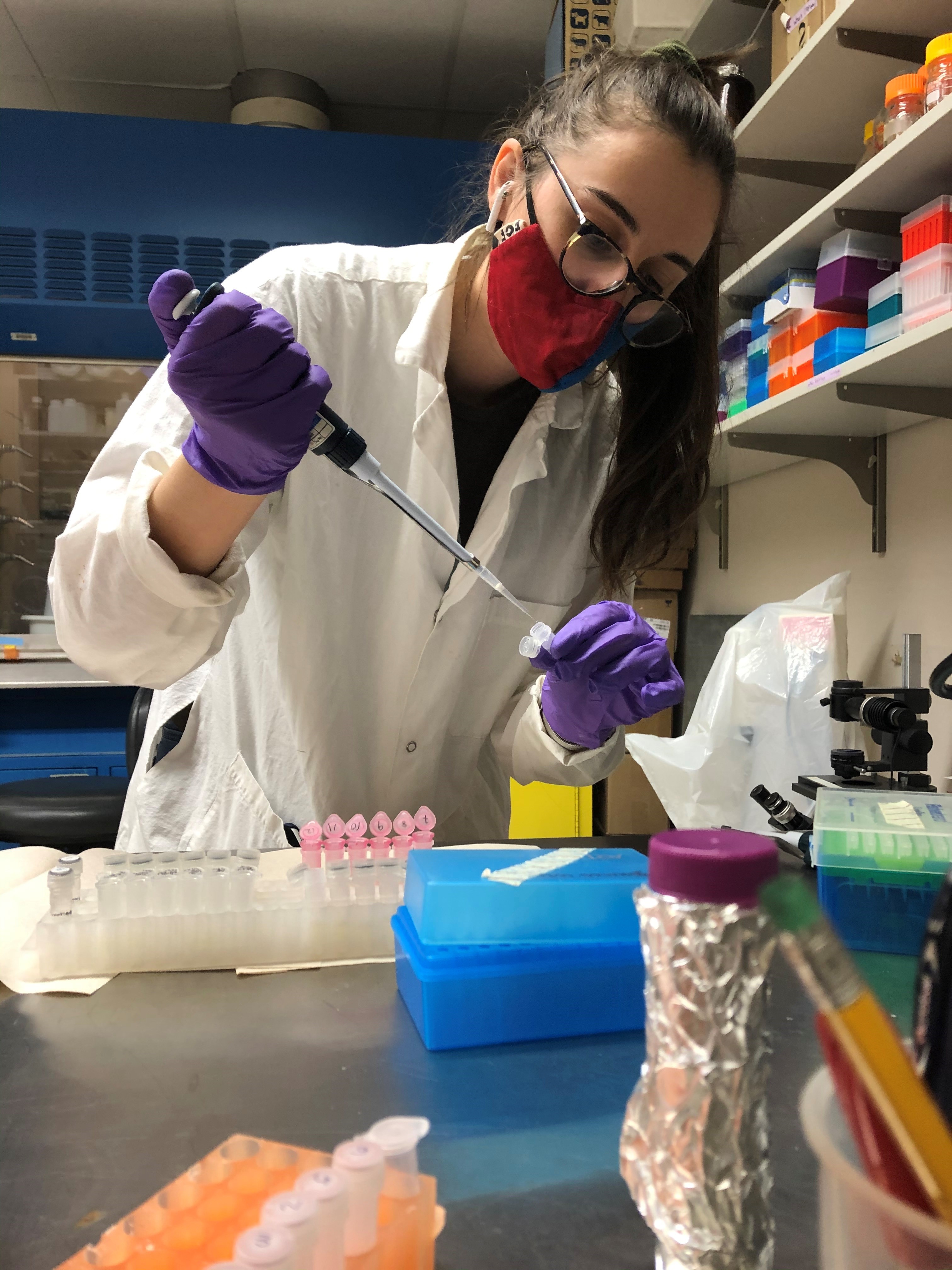

So, doctoral student Sara Hutton placed inland silverside fish embryos in a tiny amount of common pesticides for just a few days. To put it in perspective, the scientists exposed the fish to about the same concentration of pesticides as a teaspoon of them in an Olympic-sized pool.

The embryos hatched into the solution and stayed there for four days, after which researchers moved the fish larvae to clean water, where they grew.

“It turns out when the fish hatch is an incredibly sensitive window,” Brander said. “The early four-day exposure led to effects in adults and in the offspring.”

The scientists found the fish and their offspring behaved strangely, like looking for too little or too much food. The adult male fish also had smaller reproductive organs and the adult had altered the number of eggs produced by female fish.

“It’s a bit of a red flag,” Brander said. “We should be looking into this because it could be contributing to population decline, potentially in lots of different fish species.”

This sensitive window has shown up in other endocrine-disrupting chemicals, such as bisphenol-A, commonly known as BPA, she said.

Moreover, she said, fish have similar hormones as people, from estrogens to androgens to stress hormones. In fact, researchers often use fish that are similar to silversides as models for human health studies.

That’s why, Brander said, she worried about people’s exposure to these pesticides, especially for people who are pregnant or young children. It’s something scientists need to study more.

“I would be concerned about early-life exposure, in-utero exposure, if you’re spraying this around your home, or if you’re exposed due to working in agriculture,” Brander said.

One solution, she said, would be to limit the use of these pesticides.

The study was published in the journal Environmental Science and Technology.