EPA Proposes adding portions of 150 mile stretch of upper Columbia River to the Superfund list

Listen

(Runtime :54)

Read

The federal government is taking public comment over a proposed massive cleanup project on the upper Columbia River. The Environmental Protection Agency wants to put the site on the Superfund National Priorities List.

The public can comment through May 6th.

The Superfund designation would make the upper Columbia River eligible for remediation from the U.S.-Canadian border south to the Grand Coulee Dam — impacting portions of those 150 river miles.

“The impacts from the contamination continue to pose risks to human health, disproportionately impacting low-income and tribal residents, and risks to the environment,” said Carrie Sessions, a senior policy advisor to Washington Governor Jay Inslee.

The EPA has determined that soils contaminated with lead and arsenic are a health hazard, especially for children. The EPA said that soil in at least 194 residences and parks in the proposed region contain too much lead.

“Today’s [Tuesday’s] action builds on decades of efforts to clean up the river and protect the health of people who live, work, and recreate in and near the Upper Columbia,” said EPA Region 10 Administrator Casey Sixkiller in a press release. “Listing this site on the National Priorities List unlocks the full suite of tools and resources of EPA’s Superfund program to address this complex site and take additional steps to protect young children from harmful levels of lead.”

Workers scrape away the top soil at a remediation site at the Lyn Kaste Gould Memorial Park in Northport, Washington in 2020.

(Credit: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency)

Lead

Lead poses a health risk to people through direct contact or accidental ingestion of soil, including from yards, gardens and play areas. Lead can severely harm mental and physical development in infants and children – slowing down learning and damaging the brain. In adults, lead can harm kidney function and cause high blood pressure, heart disease, or cancer.

Lead contamination disproportionately affects young people and minority groups along the Columbia River, including the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, Washington state’s Sessions said.

Jarred-Michael Erickson, Chairman of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation said in a press release, “Historical disposal and discharges of wastes and emissions from smelter operations have contaminated the UCR [Upper Columbia River] Site and pose a risk to human health as well as to the sovereignty and economic security of the Colville Tribes. An NPL listing will allow access to resources that are much needed for remediation of the UCR Site.”

Teck Metals

The main source of contamination in the upper Columbia River area is the Teck Metals, Ltd. smelting facility in Trail, British Columbia. That’s about 10 river miles upstream of the international border. The former Le Roi smelter in Northport, Washington, also added to the contamination.

The Teck Metals facility produces zinc and lead along with a variety of precious and specialty metals, chemicals and fertilizer products at its Trail facility, according to the company website.

Cleanup would likely take years, EPA officials said, but the Trail facility will continue to operate.

Under a 2006 agreement, Teck – a Canadian company – has already paid for some cleanup of contamination in Northport, Washington and in Black Sand Beach near Northport. “The enforceable agreement [from 2006] does not require Teck to complete a comprehensive cleanup of the site,” an EPA press release said. Placing the site on the Superfund list means access to federal money which can help speed studies for the cleanup and the cleanup itself. Whether Teck will be on the hook for any further cleanup will play out over the next several years, EPA officials said.

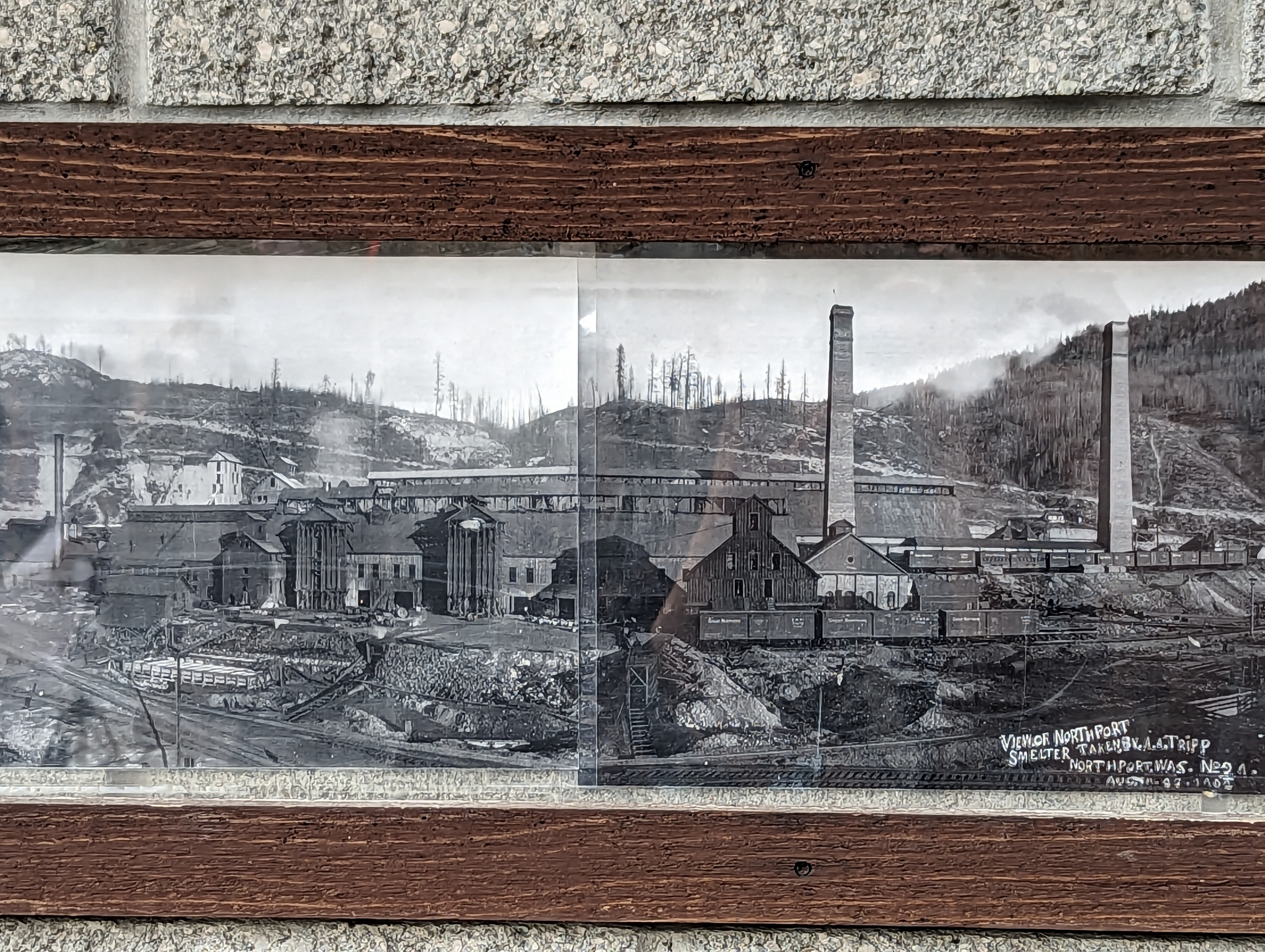

Historical images of the Le Roi Smelter, that is no longer in operation.

(Credit: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency)

History

For the past 20 years, Washington’s Department of Ecology, the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation and the Spokane Tribe of Indians have been working with the EPA to try to understand the historical contamination from Teck. Following the 2006 settlement, the process has been stuck for a while, said Brook Beeler, Eastern Region Director with Ecology.

“What this listing does is add more tools to EPA’s tool box, to be able to act more quickly,” Beeler said. “So they can push a bit harder on Teck in some instances. Or they see there is an immediate risk to people or the environment they can compel action right away and if there’s Superfund dollars at the federal level then there is also opportunity to tap into the funding resource as well.”

Beeler said the contamination not only affects the Columbia River shore, but also some upland areas outside of the rivershore – as well near the community of Northport, Washington.

The last major site the EPA listed in Region 10 was Bradford Island in June of 2023.