Clarkston homeless facing another move as camp is forced to close

Listen

(Runtime 4:09)

Read

By Rachel Sun, Kerri Sandaine and Eric Barker

Homeless people living near the Walmart in Clarkston have until 5 p.m. Sunday to find a new place to stay.

Clarkston police arrived at the camp around 10 a.m. Wednesday to issue notices of trespass and talk to residents about the changes. Anyone who remains at the site after the deadline will receive trespassing violations, officials said.

The only city-owned spot available for overnight stays is Foster Park, located near Diagonal and 10th streets. Homeless individuals can sleep there from 9 p.m. to 7 a.m., but they cannot leave their personal belongings at the park during the day.

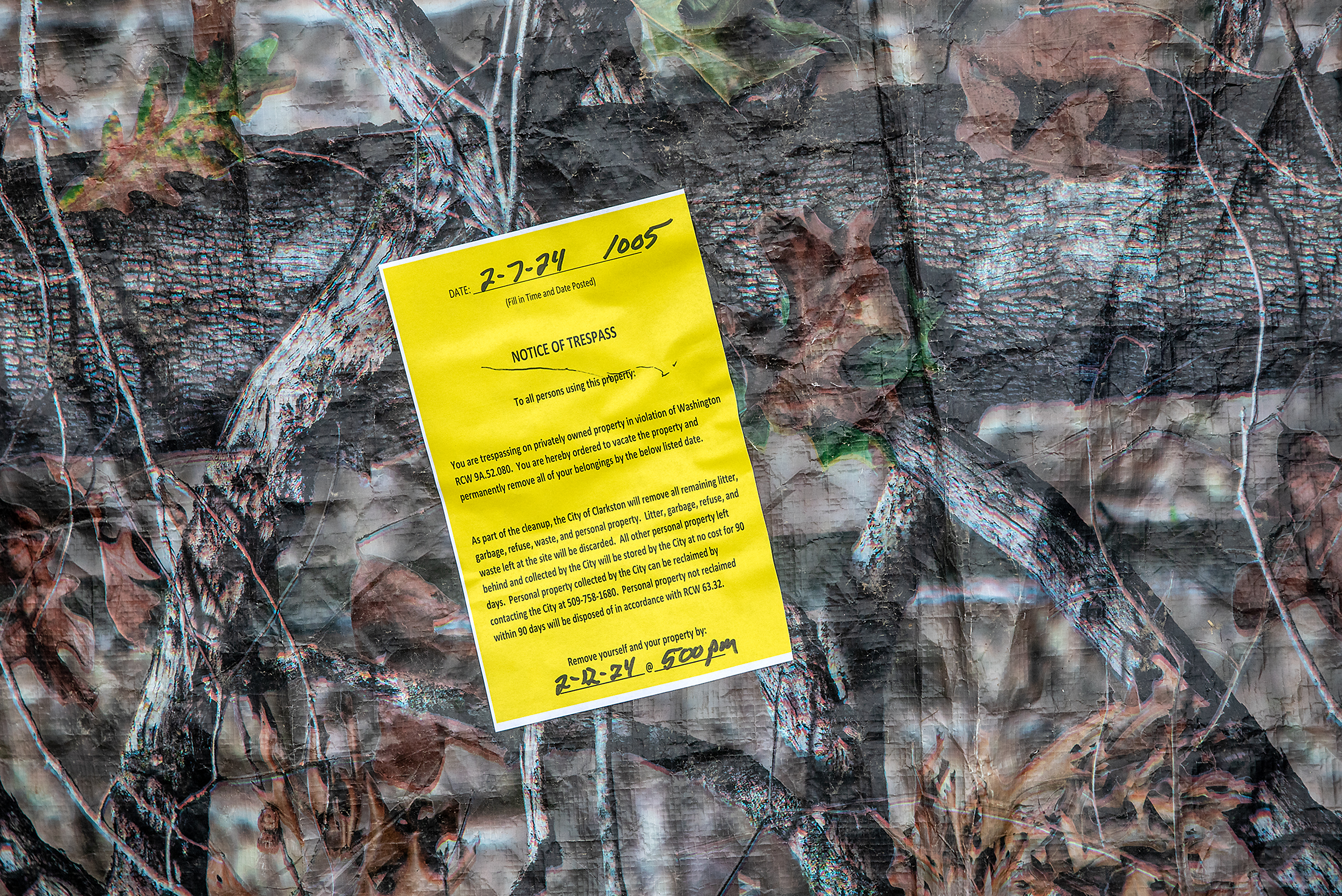

A notice of trespass sits on a tent at the homeless camp behind Walmart Wednesday in Clarkston. (Credit: August Frank / Lewiston Tribune)

Local business owners and good Samaritans are now scrambling to find a place for homeless residents in the Lewiston-Clarkston Valley following the city council’s recent approval of an ordinance outlining the new rules. Camp resident Scott Darrington said there were roughly 100 camp residents by the last headcount.

The property next to Walmart, previously thought to be owned by the city, was found to be privately owned. According to a Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruling, homeless people cannot be punished for sleeping on public property when they don’t have other options.

An emergency council meeting Tuesday left it unclear how long campers would have before facing arrest for trespassing, leading to heightened tension among some camp residents and their supporters. Several people at the camp spoke about the situation on Wednesday.

“The city hall meeting lasted all of not even five minutes last night,” said camp resident Brandon Rivas. “How can you determine our lives in less than five minutes?”

John “Cowboy” Parke, who attended the council meeting, said he was thankful for the community support at the standing-room-only session.

John “Cowboy” Parke shakes hands with Clarkston Police Sgt. Bryon Denny as notices of trespass are served Wednesday in Clarkston. The police are giving camp residents until Monday, Feb. 12, to vacate the property. (Credit: August Frank / Lewiston Tribune)

“I freaked out at city hall the other day, and that was bad. I apologized to everybody for that. But the whole community came together, and there’s a plan, there’s people working on getting a spot for us,” Parke said.

Some of those people include local business owner Cory James and pastor Nick Hasselstrom.

James is looking for properties to buy, and said he is looking into leasing a property to where homeless people could move as a stopgap.

Clarkston police make their way through the homeless encampment located behind Walmart as they serve notices of trespass Wednesday in Clarkston. The police are giving camp residents until Monday to vacate the property. (Credit: August Frank / Lewiston Tribune)

“If we can pull this off, this will give us something. Even if we just sign a year lease,” he said. “That’ll buy us about a year to where we can get some property.”

The two are also going to be looking to local churches to contribute financially, Hasselstrom said.

“I’m gonna say, ‘Well, get into your coffers a little bit.’ The churches could come up with enough money, we could get some property,” Hasselstrom said. “ I know there would be liability insurance that would probably have to be taken care of, but we got enough churches in this town.”

Hasselstrom said he would also put in $10,000 toward funding a place for homeless residents to stay.

City officials also provided maps of publicly-owned land in the valley. However, several areas marked on those maps included riverside property, which is managed by the Army Corps of Engineers.

On Wednesday, the Corps closed off the Greenbelt boat ramp for an indeterminate period of time to guard against a potential “influx of people” and unspecified “safety concerns,” a spokesperson for the agency said.

“They trespass us, too,” said Dylan “Montana” Evenson, a camp resident.

James said he blames the city for allowing homeless residents to camp at the site without confirming the property was publicly owned.

“So now everybody’s got everything they own, and everything they’ve collected for the last few months, sitting in piles outside their tent,” James said. “Where the hell are they going to put it?”

Scott Darrington exits his tent carrying Big Pimpin as a notice of trespass sits on the front of it Wednesday at the homeless camp behind Walmart in Clarkston. (Credit: August Frank / Lewiston Tribune)

Evenson said he’s probably going to move closer to the river, despite the Army Corps, when he leaves.

“People gotta start busting butt, getting stuff packed up. But we should have enough help to get over there,” he said.

Scott Darrington, 47, said he’s been collecting tents that have been damaged or abandoned to either fix up or use parts of, to add protection over the windows for other tents that are being used.

“I got like 32 tents now,” he said. “I gotta pack up and figure it out where to put ‘em.”

While the valley’s unhoused residents try to figure out their next move, they’re also still struggling with winter living and daily challenges accompanying homelessness.

“[I’m] getting ready to go find out if I got to lose any toes or not from frostbite,” said Darrington, who was preparing to leave for a doctor’s appointment. “If what the CHAS clinic told me is true, at least the first two on each foot will have to go. My fingernails are turning that same color right there and my toenails are, which is a sign of frostbite under the nails.”

Tiffany Deen, 42, said she’s been living at the camp for about two weeks after coming from a domestic violence situation.

“This is 100% better than where I was, because nobody puts their hand on me here to hurt me,” she said. “These guys are like my protection.”

She explained the person she left found her at the camp.

Hasselstrom will be holding a Sunday service at the camp at 1 p.m., he said.

“I’m not going to preach hellfire and brimstone. I’m gonna preach the love of God, because these are real people,” he said.

In a prepared statement, Danika Gwinn, clinical director of Quality Behavioral Health, said that what’s happening in Clarkston has helped shine a light on the problems unhoused individuals are facing.

“Though it is disheartening to receive the news that individuals will be moving again and have to find new places to be, it has allowed so much more transparency in our community and acknowledgment that affordable housing is an issue,” Gwinn said. “And the stigma surrounding mental health, substance use and poverty is still very real in our community.”

QBH is a nonprofit organization that runs the state-funded Navigator Recovery Program. Staff members are frequent visitors to the homeless camp as they assist people needing help with substance use disorders or unmet behavioral health issues.

Over the past few months, many valley residents also have stepped up to help the unhoused, Gwinn said.

“It is humbling to see all of those who did help those in need and continue to do so. Despite the differences in beliefs by one another, it has brought together a catalyst for change and a need to actively work on solutions as a community – and that’s a win.”

This report is made possible by the cooperative agreement with NWPB, the Lewiston Tribune and the Moscow-Pullman Daily News.