Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Maestro

“A work of art does not answer questions. It provokes them, and its essential meaning is in the tension between the contradictory answers.”

–Leonard Bernstein

That observation from Leonard Bernstein appears at the beginning of Bradley Cooper’s new film, his second feature as a director. He has clearly matured in that respect since the admirable A Star Is Born (2018), another story about a couple’s relationship against the backdrop of the musical world. Like its legendary subject, Maestro inspires admiration and prompts all kinds of second guessing.

It starts with the prosthetics and the voice. Bradley Cooper does, indeed, look remarkably like the real-life Leonard Bernstein, especially in his later years. And he manages to produce the very distinctive nasal sound (bordering on a growl) that came to define Bernstein as the great verbal communicator. Oh, yes, the cigarettes. Lenny was never without a smoke, and neither is Cooper here.

Beyond that, the movie makes no concessions to those who don’t have an encyclopedic knowledge of Bernstein’s life. In fact, Cooper the director emphasizes that at the outset, in dazzling fashion. The 25-year-old Bernstein awakes to a phone call summoning him to conduct the New York Philharmonic on very short notice, without any rehearsal, for a nationwide radio broadcast. We catch a glimpse of his male lover as he scrambles to get dressed, rush out the door, dash down the stairs and appear on the balcony of Carnegie Hall. Working with cinematographer Matthew Libatique (The Whale, A Star Is Born) and editor Michelle Tesoro (The Queen’s Gambit), Cooper gives us a fluid, seamless, whirlwind prologue to a brilliant musical career and an ambitious film, replete with a blacked-out window become a stage curtain.

As Maestro intersects with Bernstein’s personal life over the course of the next three decades-plus, Cooper makes another bold decision. He gives the story its beating heart by focusing on the relationship between “Lenny” and the Costa Rican-born actress Felicia Cohn Montealegre. They meet “cute” in 1946 at a party hosted by one of her teachers, the renowned Chilean pianist Claudio Arrau. They married in 1951, and their 27-year union produced three children, all of whom lent their strong support to the making of Maestro.

This first act plays out in a crisp, luminous black-and-white format. Bernstein is energetic, ambitious, multi-talented and bisexual. Felicia is also gifted, as well as charming and knowing. They move in a rarefied circle: Aaron Copland, Artur Rodzinki, Serge Koussevitzky, Betty Comden and Adolph Green. Lenny laments that “the world wants us to be only one thing, and I find that deplorable.” Felicia readily (and mostly) appreciates that a relationship with him will be challenging, given his ferocious embrace of life and art. The actress who portrays her appears with the onscreen title and receives top billing. Carrie Mulligan, already a two-time Academy Award nominee (An Education, Promising Young Woman), here offers another beautifully, at times heartbreakingly, nuanced performance.

With the leap ahead to 1971, the film transforms itself into a kaleidoscope of color, a succession of set pieces and a thoughtful personality study. Lenny wrestles with the very range of his musical obsessions, from the concert hall to the Broadway stage to the opera house. His genius overlaps his devotion to Felicia and their children, even as his sexual appetite manifests itself on a continuing basis. A veritable fugue of experience and achievement. An ode to a man who could never accept being “only one thing.”

Cooper’s choices as writer-director may have devolved into a disconnected “greatest hits” biopic–admittedly, some scenes could use more fluid transitions–but he mostly avoids that. The film has a discernable formal structure, and the pivotal scenes have emotional and narrative meaning. Respecting Bernstein’s prodigious musical output, they sometimes betray flights of fancy. In one memorable sequence, Lenny becomes one of the sailors in his 1944 musical On the Town. The duality of his attraction to men and fierce love for his wife intertwine in a suggestive dance set in a suspended world of imagination and desire. Fellini would have been proud of Cooper.

As a viewer, you can sense it coming. The earlier dancing camerawork gradually becomes more static, even distant at times. The restless Lenny and the self-possessed Felicia have to face some hard choices and crises in their relationship. One of them, a veritable eruption of previously unspoken assumptions and grievances, takes place in their apartment at The Dakota in New York City. Simply put, it’s an acting clinic on the part of the two leads, and it’s a stroke of savage irony that a certain giant balloon makes an appearance in the Thanksgiving Day parade outside their windows. (Cooper reportedly calibrated the entire scene to that moment.)

An intense degree of preparation (and angst) went into one subsequent, climactic scene. The place is Ely Cathedral in England; the year is 1973; the work is Gustav Mahler’s Second Symphony (“Resurrection”). Copper shot it on location in one, continuous six-minute-long take, with a live orchestra (London Symphony), soloists, choir and extras. He worked with Gustavo Dudamel, the Music Director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, and Yannick Nézet-Séguin, Music Director of the Philadelphia Orchestra and Metropolitan Opera, for six years to make the moment credible. He wanted to get it right and do justice to Bernstein’s passion for Mahler’s music. The result on film is detailed and riveting, if unconventional in its placement within the broader narrative. Cooper’s face reflects the commitment, anguish and exaltation of the conductor. If his mannerisms seem contrived, watch the video of the historical event (available on YouTube and sampled at the end of the movie). Cooper supplies the final touch at the end of the performance as the camera pulls back to ultimately reveal Felicia as she waits in the wings.

The last act of this cinematic theme-and-variations transports us to the late 1970s and the latter stages of the couple’s relationship. The wealth and credibility of the emotion on screen has been earned. Bernstein engages in a different kind of embrace–a literal embrace–that completes this simultaneous portrait of a creative artist and a complex marriage.

Likewise, if you’ve seen last year’s Tár, in which the imperious title character (virtuosically portrayed by Cate Blanchett) rudely dismisses one of her students in a masterclass, you will appreciate Bernstein’s approach at Tanglewood, the Massachusetts institution he inhabited as a student and, later, as a conductor-mentor. His charisma never waned.

In addition to Ely, Tanglewood, Carnegie Hall and The Dakota, Cooper makes effective use of the Fairfield, Connecticut house where the Bernstein family lived for many years. Production Designer Kevin Thompson (Ad Astra, The King of Staten Island) gets high marks for his meticulous attention to period detail spanning the 1940s into the 1970s. True to its time, the music, too, goes beyond Bernstein and Mahler. R.E.M. makes a telling–and amusing–appearance on the soundtrack, as Lenny stays in touch with a younger generation.

In a movie so rich in characters and dialogue (for which Josh Singer shares credit with Cooper), several members of the supporting cast stand out. They include Matt Bomer (as David Oppenheim, a talented clarinetist and early Bernstein lover), Sarah Silverman (as the title character’s no-nonsense sister, Shirley), and Maya Hawke (as Jamie, the oldest of the Bernstein children, who shares an exquisitely awkward conversation with her famous father about his sexuality). We even get to hear from the legendary journalist whose name graces the College of Communication at Washington State University. As with any biopic, we can take issue with the dramatic choices and liberties pursued by the writers and directors. With Maestro, we can also cite the differences in the acting styles of the two principals, however talented. Mulligan has a natural, unaffected technique that allows her to disappear into her character. Cooper, so committed to this project, has a more formal manner. He impresses with the execution of his portrayal. In the end, he manages to wear all of his hats here–co-producer (with Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese), co-writer, director and lead actor–with real dexterity. Maestro is suffused with the music, mannerisms, intensity, complexity and larger-than-life persona of its subject. Whether you’re already familiar with his story or not, Leonard Bernstein lives here.

More Movie Reviews:

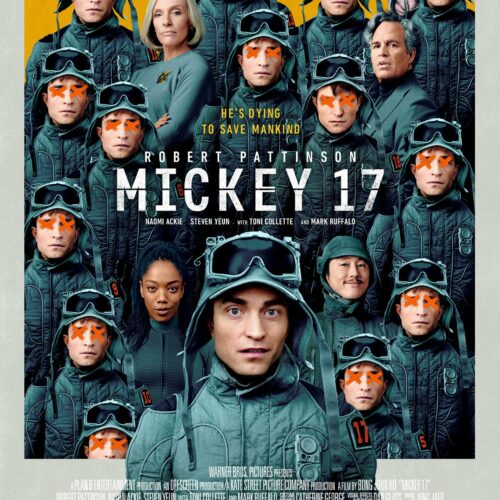

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Mickey 17

Movie poster of Mickey 17 courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures. Read “You don’t look like you’re printed out. You’re just a person.” In writer-director Bong Joon Ho’s new science fiction

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: A Complete Unknown

In director James Mangold’s new film, Timothée Chalamet portrays the young Bob Dylan (the professional name he adopted at age 21) from 1961-1965. He gives a remarkably nuanced, accomplished performance in a movie that occasionally gets bogged down in truncated or unnecessary scenes, but not too often. The supporting cast shines as well.

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Nosferatu

A classic tale laced with horrific, religious, folkloric and erotic themes. Robert Eggers seemed destined to make a movie about it. Finally, after a decade of preparation, he has.