Overtime law remains in dispute among farmworkers

Listen

(Runtime 3:51)

Read

Farmworkers have met in central Washington to talk about a new overtime law and how it’s impacting their incomes. Farmers say it’s not sustainable for them. Nonprofits organized rallies in Quincy and Sunnyside and have planned others for the future around Central Washington.

Leonardo Florez is a local farmworker from Quincy. He says the overtime law has had a dramatic impact on his income.

“La verdad para nosotros el programa de overtime no ha funcionado. Al contrario, en vez de ser un beneficio ha sido un maleficio. La familia recibe menos,” said Florez.

Instead of being a benefit it is a curse, he said. He said his family is getting less.

Gilberto Gonzalez, a worker who came from Mexico says this is his second time working in the U.S, but the conditions have changed a lot since his first.

“En el 2017 podíamos meter más horas. Eran 70 horas a la semana, 65 horas a la semana. Y hoy me encuentro con la triste realidad de que nada más son de 35 o 36 horas por semana,” said Gonzalez.

Gonzalez said before, he was working 70 hours a week and now only about 35. He also said it’s not enough to cover his expenses and send money to his family abroad.

This rally in Quincy was organized by the Center for Latino Leadership. Maia Espinoza is the Founder & Executive Director of the organization.

“What we heard today from workers is that they would like to work more hours. And while the overtime law does not prevent them from working more hours, that we know would give them extra pay to be able to work those hours, it’s not sustainable for the farmers,” said Espinoza.

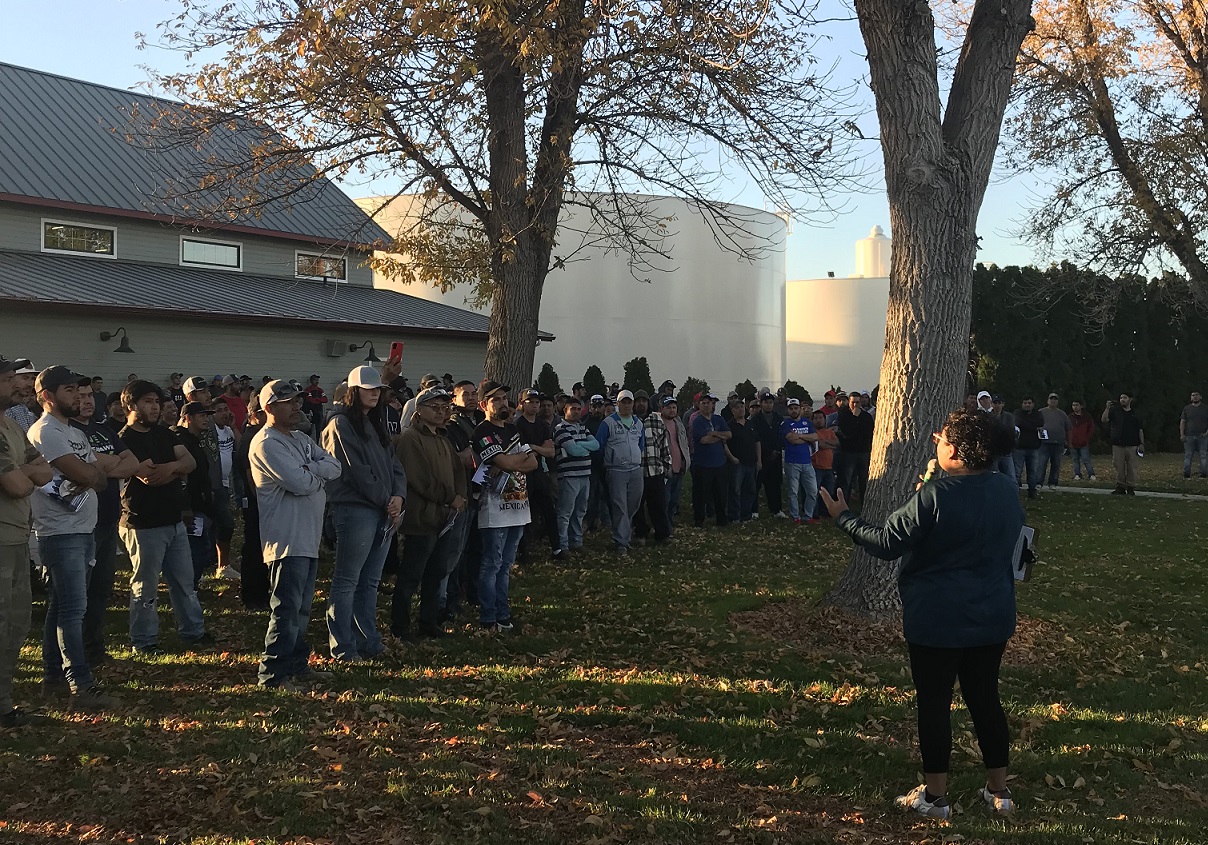

Farmworkers at South Hill Park, in Sunnyside, during a rally about the agricultural overtime law. (Courtesy of Save Family Farmers).

Kent Karstetter is a Quincy farmer. He says the idea of rich farmers refusing to pay overtime is far from reality.

“When you make a lot of money, you pay a lot of taxes. I don’t get my money ’til next year. My boys harvest their crop of beans, and they won’t get paid for 3, 6, 9 months. If you think that we’re that greedy and rich, then why are we still doing this job,” said Karstetter.

Jesus Limon, another farmer from Quincy, said the amount of money received per pound of cherry does not compensate for the production costs.

“Esta desde los 18 centavos hasta los 50 centavos. A nosotros para pizcar una Cherry nos cuesta 30 centavos; entonces 18 centavos no nos da ni para pagar 40 horas regulares, menos para pagar overtime.”

Limón explained that the rate per pound of fruit ranges between 18 and 50 cents, when picking fruit costs 30 cents. That is not enough to pay for 40 regular or overtime hours, he said.

Limón said that doesn’t include other production costs.

Karstetter says the situation affects everybody.

‘When I send my workers home at 39 hours, I don’t need my supervisor anymore. I don’t need my truck driver. I don’t need my tractor driver. None of us are safe in this thing. It is a house of cards. And I honestly don’t know how to fix it,” Karstetter added.

Florez said he doesn’t blame the farmers.

“Están trayendo más gente contratada. Levantan la misma cosecha, la misma producción, con más gente,” said Florez.

They are getting more foreign workers, getting their harvest and same production with more people, Florez said.

He said local workers are at a disadvantage.

“El contratado llega y se hospeda, le dan herramientas, le tiene vivienda. Le tienen transporte. El local tiene que proveer sus propias herramientas, paga renta, paga biles, comida,” said Florez.”

Florez explained that while the H2A has tools, housing and transportation, the local farmworker must provide their own tools, and pay for rent and food.

Washington Representative Alex Ybarra said while the law had good intentions, not all farmworkers work under the same conditions.

“We have 90% of all the farm workers and yet, what they listen to is the people over in Northwest Washington. Five percent unions allá y nosotros tenemos all the rest of the farmworkers here. There are no unions over here,” said Ybarra.

But Antonio De Loera-Brust, the communications director of United Farm Workers, disagrees.

“This idea that overtime is something from the west side of the state that people in the Yakima Valley don’t want. That’s just not aligned with what actually happened and how this law came to be. Workers from the Yakima Valley were who led this fight for overtime pay,” he said.

De Loera-Brust also said listening to farmworkers during the rallies about the overtime proves the poverty wages that farmworkers are paid.

“One of the workers says very clearly eight hours of work is not enough for us to make ends meet. Eight hours of work, regardless of what your job is, should be enough to raise a family in this country. That’s the American dream,” he said.