WSU researchers find 41 percent of U.S. women have no abortion access within 30-minute drive

Listen

Read

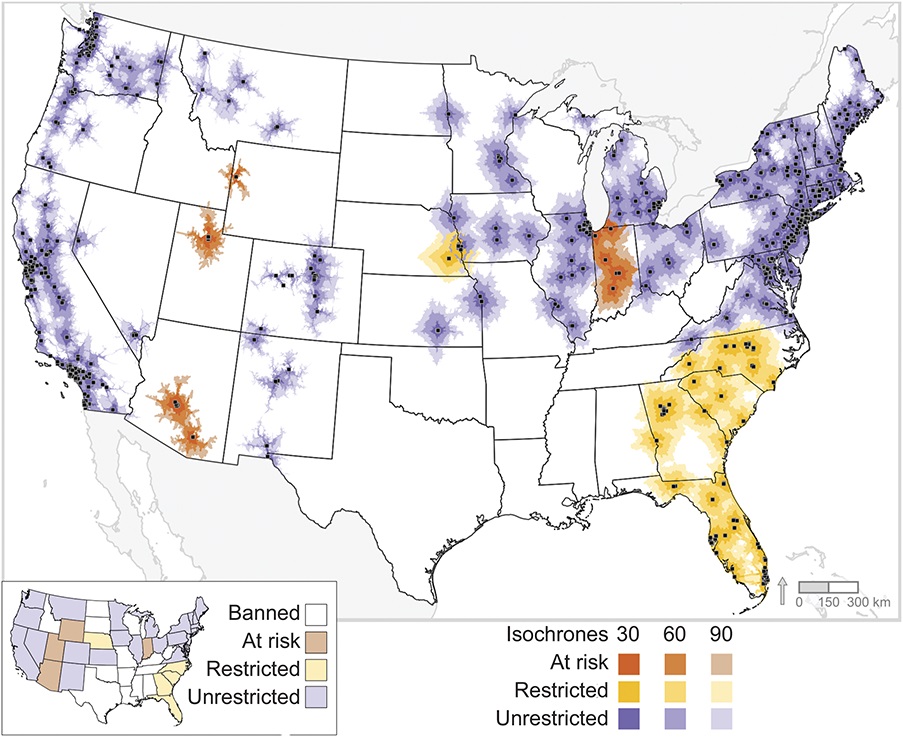

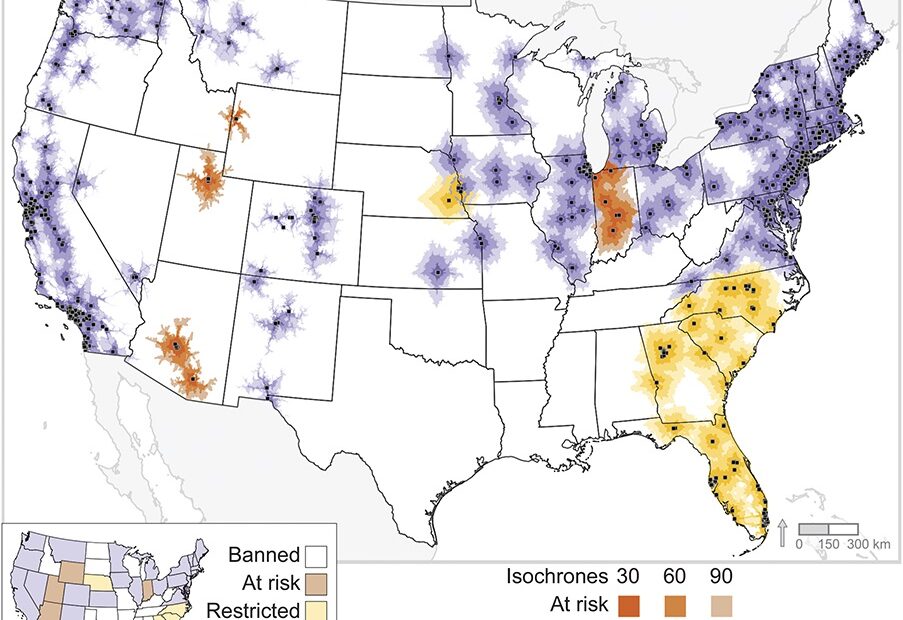

More people seeking abortions must travel for care because of bans or restrictions in their home states. Researchers at Washington State University found that 41.4% of American girls and women between the ages of 15 and 49 have to drive more than 30 minutes to access an abortion provider.

That totals about 30.8 million women, said senior author Dawn Kopp.

The report, published in the journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, found another 29.3% had no access within a 60-minute drive, and 23.6% did not have access within 90 minutes.

Kopp said the team wanted to understand the current patient experience, and look at how things could change in the future if more states restricted abortion access. People with less money are the most likely to be affected by abortion bans and restrictions.

“We know that depending on certain socioeconomic factors and other disparities, not everyone can overcome a 30- or 60- or 90-minute driving time,” she said.

In Idaho, where abortion is completely banned, 7.7% of women ages 15 to 49 had access within 30-minute drives, 13% within 60 minutes and 16% within 90 minutes.

Jennifer Tang is an OB-GYN practicing in North Carolina, and a co-author of the paper. One piece of information the research data doesn’t fully capture, she said, is that many patients drive much more than 90 minutes. North Carolina doesn’t have a total abortion ban, but still severely restricts abortions.

“It’s often not just a 90-minute drive, or we’re talking 120-minute drive, we’re talking like, five hours, eight hours, 15-hour kind of drives that people are having to make,” she said.

For many of the people who get abortions, Tang said, those added challenges are an even bigger burden. People who seek abortions are more likely to be low income, with about half, as of a 2014 study, living in poverty.

“You need to find money for the travel. If you’re even lucky enough to get that, you need to find childcare, because the majority of people who have abortions have a child already,” Tang said. “Then you have to add in possibly hotel costs, days off from work. That’s a very tricky thing for low income people to navigate when their jobs may not be as generous with leave benefits.”

The data falls in line with similar reports about women spending more time and money to travel for abortions. The Northwest Abortion Access Fund, which provides financial and practical support to people seeking abortions, reported a jump in costs from $913,519 in 2021 to more than $1.7 million in 2022.

Several groups have sued states with abortion bans, including Idaho, after they were unable to access abortions in their home states. Jennifer Adkins, a Boise-area mother, drove six hours to Portland, Ore., to terminate a pregnancy that could have led to life-threatening complications. She is now a plaintiff in a suit against the state.

As Tang’s home state of North Carolina tightened restrictions, more patients who would have previously gone to her are adding hours to their drive, she said. The same is happening across the country.

“You’re having to choose between doing the right thing for your patient and possibly being fined by the North Carolina Medical Board or [a doctor’s] state medical board,” Tang said. “That kind of stuff is really not what providers want to deal with. And so it’s easier just to say, ‘Go to Virginia.’”

Although states like Idaho have much lower access, even those with the most abortion protections in place still have areas with limited access.

“Even in states that have very few restrictive laws, you can see the white spaces [on the map] where there is no abortion access, either between 30-, 60- or 90-minute drives,” Kopp said.

In Washington and Oregon, which passed multiple laws to increase and protect abortion access, a respective 86% and 74% of women between the ages of 15 to 49 have access within a 30-minute drive.

“State laws are part of the picture. But they’re not the complete picture,” Kopp said. “There’s also geographic access. And there’s also: number of facilities and health care professional access that we need to take into account.”

To calculate travel time, the team collaborated with DataLab at the University of California, Davis, to create map lines.

In addition to looking at current restrictions, the team also looked at “at-risk” states with proposed restrictions.

They included Indiana, Kansas, Nebraska, Ohio and Wyoming. Many, the authors wrote, had legal action blocking anti-abortion legislation. If those restrictions went into effect, the percent of women between 15 and 49 with no clinics within a 30-minute drive could jump from 41.4% to 53.5%.

The study also notes some limitations. The age range used and gender limitation may not capture all people capable of becoming pregnant, but does account for a large portion of them.

Kopp said the study could be repeated. Their findings could also be helpful in understanding rural health care access across other specialties, she said.