Toxic algae found in Columbia River for third week, EPA scientists on the way and new OSU study “sniffs” for toxins

Read

The Environmental Protection Agency will begin sampling the Columbia River near the Tri-Cities, Washington next week to sort out why toxic algae keeps popping up there.

Toxic algae has been found in the Columbia River for the third week in a row in the Tri-Cities.

The EPA is looking at eight sites throughout the United States to test benthic harmful algal blooms that grow on the bottom of water bodies, including the Columbia River in Washington, Zion National Park in Utah and the Shenandoah River in Virginia.

“Our goal at EPA is to protect human health and the environment,” says Rochelle Labiosa, a physical scientist with the EPA, based in Seattle. “We are really concerned when we see events like this and so that’s why we took on this project.”

The EPA team of four scientists will study one site on the Columbia next week near Richland and monitor it intensively. The team will return in early October for more testing. Next year, the project is expected to expand to four different sites if the agency has the funding in place.

There is also a blue-green algae bloom in the middle section of Moses Lake and an advisory in Potholes Reservoir, both in central Washington. In Oregon, there has been toxic algae in the Willamette River running through Portland – the Ross Island Lagoon and Willamette Cove are still under advisories.

The latest results off the Columbia River show the neurotoxin anatoxin-a is present at a level much higher than the Washington state standard for safe recreational use.

“We just want to alert people to the problem,” said Jim Coleman, with the Benton Franklin Health District, in the Tri-Cities. “We don’t want to shock them or scare them away from the river. It seems like it is difficult to track because it’s a river and it’s moving. We just want people to know that it’s out there. It is sort of localized. Certain areas can be worse than others. For instance right now Howard Amon [Park] seems to be the hotspot.”

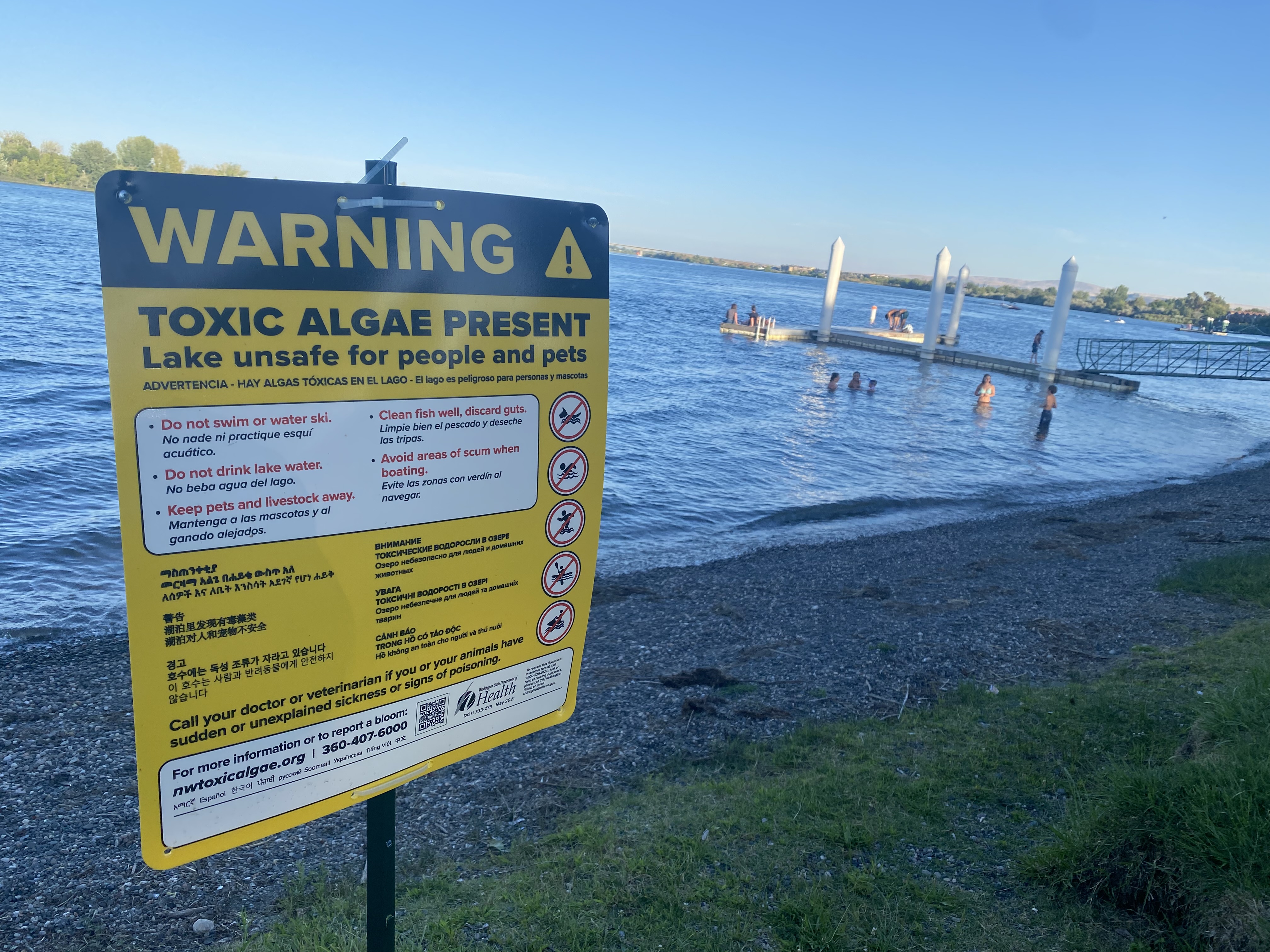

The toxin is especially dangerous for small children and animals. Warning signs are posted in the affected area around Howard Amon Swim beach, although people continue to use the water in that area.

“It’s a little frustrating when you put the signs up and people just walk right by them and jump in, or whatever,” Coleman said.

A massive late-stage algal bloom on Upper Klamath Lake in Oregon. The turquoise color is algal pigments being released during cell death. (Courtesy: Lindsay Collart)

A massive late-stage algal bloom on Upper Klamath Lake in Oregon. The turquoise color is algal pigments being released during cell death. (Courtesy: Lindsay Collart)The toxins are hard to track as a mix of many organisms make them. Now, researchers at Oregon State University have developed a new way to monitor the danger associated with algae blooms that occur at the surface of the water. The researchers “sniff” the water for gasses associated with the toxins with a special machine called a mass spectrometer that detects all of the gaseous molecules simultaneously. OSU Associate Professor Kimberly Halsey leads the study that was published in mSystems.

“Here’s this wide array of chemicals that appear to have a language that we are only now starting to sort of translate and understand what it’s saying to us,” Halsey said. “And if we can say, hey, we can translate some of that information and protect the public I think that’s pretty exciting.”

Different cyanobacterial species produce different toxins. Many of them are clear, odorless and tasteless. Most of them cause gastrointestinal illness and bad skin rashes. The toxins can also be deadly. In 2017, more than 30 cattle died after drinking contaminated water at Junipers Reservoir near Lakeview, Oregon, and several dogs died in the Tri-Cities a couple of years ago from toxins in the Columbia River in 2021.