Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Oppenheimer

“Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

–Arjuna in the Hindu scripture Bhagavad Gita, as cited by J. Robert Oppenheimer

Biopics are notoriously fraught with difficulty. They have to achieve an emotional and intellectual resonance, as well as a period look and feel. The script has to reflect and enhance the inherent drama in the lives of its characters, and the main one really has to matter. In Oppenheimer, the British-American writer-director Christopher Nolan embraces the challenge of telling the story of the “most important person who ever lived,” as he puts it.

This talky, three-hour-long epic, a veritable compendium of cinematic grammar and technology, unfolds in three distinct phases. It has at least as many perspectives, to which you’re invited to add your own. It features an all-star cast, even in relatively minor roles, and it displays the obsessions of both Oppenheimer and Nolan.

As the lead here, the Irish actor Cillian Murphy (28 Days Later, Peaky Blinders) gives an astonishing performance. His slight frame, angular cheekbones and translucent blue eyes–his fellow cast members have referred to them as “ocean eyes”–all help convey J. Robert Oppenheimer’s probing intellect and nagging, debilitating doubt. He also replicates his character’s physical mannerisms with a high degree of precision, including the way he holds the inevitable cigarettes. Given his penchant for authenticity, Nolan actually shaped the production schedule to accommodate Murphy’s different haircuts, rather than resorting to wigs. To paraphrase his subject’s wife in the movie, this is Murphy’s moment as an actor, as he embodies the scientist become war hero become Cold War era scapegoat.

The narrative unfolds in broad sections: the Cambridge, Göttingen, Princeton and Cal-Berkeley years (1924-1942), the Manhattan Project period (1942-46) and the post-war aftermath (1946-1954), when his political and scientific opponents questioned Oppenheimer’s loyalty and challenged his security clearance, even as he became more passionate about his fears of a nuclear apocalypse. It makes for a gripping, if drawn out, tale.

In reality, Nolan effectively subverts the biopic genre, in that he regularly changes the chronology and perspective. We first meet the young Oppenheimer as a brilliant, impatient post-graduate researcher and theoretical physicist. The other extraordinary minds who would find their way to Los Alamos, New Mexico at the height of the Second World War also begin making appearances, including Edward Teller (a perfectly cast Benny Safdie). A self-deprecating Niels Bohr (Kenneth Branagh), a down-to-earth Albert Einstein (Tom Conti) and the ever-loyal Nobel Prizewinner Enrico Fermi (Danny Deferrari) help complete this all-star scientific universe. What we–and Oppenheimer–will come to appreciate is how personality and power can corrupt the pursuit of “pure” knowledge. Even as the new Barbie film luxuriates in fashionable pink, this picture exudes moral gray.

Two women figure prominently in the screenplay, which Nolan adapted from Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s biography of Oppenheimer, American Prometheus, initially published in 2005. Jean Tatlock, a Stanford-trained psychiatrist and member of the Communist Party of the United States, began a passionate on-again, off-again relationship with “Oppie” in 1936. She eventually took her own life in San Francisco in 1944, and scholars often cite Oppenheimer’s naming of the first test of a nuclear weapon–”Trinity,” from a poem by John Donne–as a tribute to her. As memorably portrayed here by Florence Pugh in her few scenes, Tatlock exhibits many of the same traits of intellectual voracity and nagging angst as her lover.

Emily Blunt inhabits the role of Katherine “Kitty” Oppenheimer, the German-American biologist and botanist who married the future “Father of the Atomic Bomb” in 1940, having already become pregnant with their first child. We get glimpses of Kitty throughout the first two acts: her professional and maternal frustration, her alcoholism, her steely personality. But then, in the post-war section of the movie, she finally gets to shine. Blunt, an actor justifiably praised for her consistently sharp, incisive work on screen, owns the part.

Two other historical figures loom large in this story. Lieutenant General Leslie Groves oversaw the construction of the Pentagon and later supervised the Manhattan Project. Matt Damon gives him just the right balance of gruffness and sardonic humor in his exchanges with Oppenheimer.

As for Robert Downey, Jr., his turn as Lewis Strauss is a career highlight. Having served as chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, Strauss sparred with Oppenheimer over the construction of the hydrogen bomb. He later tried to thoroughly discredit the physicist over his alleged Communist sympathies, even while desperately trying to advance his own career during the Eisenhower Administration. Downey, Jr., is the most obvious villain of this piece, and he is terrific.

Christopher Nolan’s entire career has been defined by his embrace of the latest technology and his fervent attention to detail. In that respect, Oppenheimer can seem daunting in its kaleidoscopic storytelling. Shot largely in 70mm IMAX, the picture’s visual palette changes with the perspectives of its characters–color for Oppie’s view (“Fission”), black-and-white for Strauss (“Fusion”) and an almost period home-movie look, saturated in color, for certain domestic and outdoor scenes. One of Nolan’s longtime collaborators, the Dutch-Swedish cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema, worked with Kodak to create a new 65mm black-and-white film stock to help convey all of the characters’ faces as an intimate, distinct “landscape” of their own.

His combination of period naturalism with the occasional outbursts of surrealism–a function of Oppenheimer’s fevered imagination–give the story the iconic, compelling look it demands.

The centerpiece of the movie, of course, is “Trinity.” The ten-minute sequence of events–and the interaction of the many personalities involved in the Manhattan Project–builds remarkable tension, almost as if we’re witnessing history first-hand. Given Nolan’s disinterest, if not disdain, for copious CGI, he and his team produce the explosion at Los Alamos with an array of “natural” tricks, including a reduction in the depth of the film stock’s resolution, variable shutter speeds, under-exposure, aquariums, water, ping pong balls and metallic balloons. For all of that, the moment really does pack a wallop.

So does the original music, conceived by Swedish composer Ludwig Göransson (Black Panther, The Mandalorian, Tenet). Respecting Nolan’s suggestion that a violin represent Oppenheimer’s state of mind, and consulting his violinist-wife for advice, he’s created an atmospheric score that transitions from sentimental to “neurotic” and “horrific.” Those tritones will unnerve you. Like seemingly all of Nolan’s productions, the music is frequently mixed too loudly on the soundtrack, but it definitely keeps you immersed in the plot.

Here in the Northwest, we’re well acquainted with the role played by the Hanford Nuclear Reservation in the Manhattan Project, with its plutonium production reactor. In case you’re wondering, it gets a quick verbal and visual reference in the film, which ultimately focuses on New Mexico.

Anchored by Cillian Murphy’s thoroughly detailed performance–a true “impersonation” of a character–Oppenheimer summarizes many of Christopher Nolan’s cinematic themes. As far back as Inception, Cobb (Leonardo DiCaprio) declares that an idea is the “most resilient parasite…almost impossible to eradicate.” In the thirteen years since then, Nolan has created stories about male protagonists grappling with the disjunct between dreams and reality, loyalty and doubt, actions and (often unintended) consequences, tragic pasts and uncertain futures. His pictures play out on large canvases, with dense storytelling techniques and an eclectic visual strategy. The horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki do not appear in Oppenheimer, but watching its subject’s anguished face as he learns of the bombings on the radio amply makes the case that the moral dilemmas of one person–or one generation–will continue to radiate with those that follow. Thanks to Christopher Nolan and Cillian Murphy and their collaborators, this is a picture which engages, and challenges, with its ideas and its presentation.

More Movie Reviews:

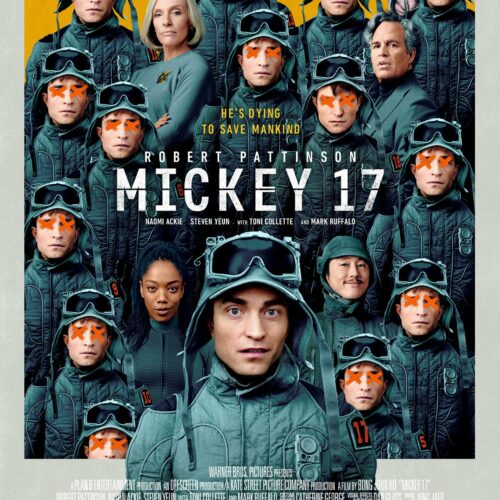

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Mickey 17

Movie poster of Mickey 17 courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures. Read “You don’t look like you’re printed out. You’re just a person.” In writer-director Bong Joon Ho’s new science fiction

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: A Complete Unknown

In director James Mangold’s new film, Timothée Chalamet portrays the young Bob Dylan (the professional name he adopted at age 21) from 1961-1965. He gives a remarkably nuanced, accomplished performance in a movie that occasionally gets bogged down in truncated or unnecessary scenes, but not too often. The supporting cast shines as well.

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Nosferatu

A classic tale laced with horrific, religious, folkloric and erotic themes. Robert Eggers seemed destined to make a movie about it. Finally, after a decade of preparation, he has.