Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Barbie

You might not have imagined a connection between the new Barbie and the acclaimed 2001: A Space Odyssey. True enough, Barbie the toy character does have pilot and astronaut on her résumé. In this case, however, she makes her big screen appearance to the accompaniment of Also sprach Zarathustra by Richard Strauss, enhanced by the droll narration of Dame Helen Mirren. 2001’s director, Stanley Kubrick, would not have seen that coming.

In fact, Barbie has been awaiting her latest transformation for more than a decade. Sofia Coppola, an Academy Award winner for her screenplay for Lost In Translation (2003), made a run at writing a film script about the iconic doll. So did Amy Schumer, the multiple Emmy-nominated comedic actress-writer. Neither could find the right tone. Too superficial, and the picture would seem silly, even pointless. Too serious, and it would sacrifice the fun. Enter Greta Gerwig.

The former muse of indie filmmakers as an actress has become a formidable talent as a director. Her first two solo efforts (Lady Bird and Little Women) both delineate strong female characters and mother-daughter relationships in psychologically believable ways. In Barbie, she offers a feminist fable wrapped inside a toy company satire, replete with a generous amount of irony and a wealth of pink.

We meet the title character (Margot Robbie) as “Stereotypical Barbie,” a living doll with an innate capacity to separate logic and feeling. She lives in Barbie Land, a welcoming kind of paradise furnished with all of the classic accessories associated with the toy. Her life seems perfect, until thoughts of mortality invade her mind. The artifice of idealized femininity has been compromised. Robbie’s performance neatly captures Barbie’s doll-like and child-like qualities, and she does excellent work with her face and her feet.

Then there’s Ken, her platonic pal. As played by Ryan Gosling, he’s a platinum blonde, singing and dancing caricature of male aspiration. (Gerwig wanted a cross between Marlon Brando and Gene Wilder. You can see it.) His persona becomes even more amusing if you recall his past as a member of The Mickey Mouse Club. And his channeling of Rob Thomas in Matchbox Twenty’s 1996 hit, Push, is almost worth the price of admission.

When Barbie and Ken depart their safe, plastic utopian realm for the “real” world of Los Angeles, they find themselves confronted with challenges and choices which had never occurred to them before. She’s dismissed by contemporary tweens and disillusioned by the all-male board of directors of Mattel, led by a rather goofy and villainous CEO (Will Ferrell). The company’s real-life Chief Executive would like you to know that it has a sense of humor, saying that they don’t take themselves “too seriously.” For his part, Ken’s encounter with toxic masculinity makes him determined to establish a “patriarchy” back in Ken Land/Barbie Land.

Gerwig and her life/writing partner, Noah Baumbach (whose own Oscar-nominated career has largely been grounded in searing, semi-autobiographical dramas), have created a meta script layered with warmth, humor, satire and history. Rhea Perlman appears as the ghostly Ruth Handler, who actually created Barbie and Ken in 1959, naming them after two of her children. She embraces her own story, which includes legal troubles, and helps Barbie discover her “humanity.”

Even more importantly, America Ferrera appears in a supporting role as Gloria, a woman trying to manage a dismissive daughter while working as an executive at Mattel, a company that sells fantasy. In the movie’s most startling scene–it does markedly, if briefly, shift the tone–she delivers an impassioned speech about the dilemmas women face every day.

Gerwig has suggested that thirty-three different films informed her approach to this Barbie. The list includes Gold Diggers of 1935, Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times, The Wizard of Oz, Gene Kelly’s An American in Paris and Bob Fosse’s All That Jazz (pictures that break down the fourth wall), Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window and Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather (which appears on a video screen). You can clearly see the influence of West Side Story and the French classic The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, especially in the choreography and the use of pastels.

The cast is pretty much ideal for the roles they play. The multiple Barbies include Issa Rae, Dua Lipa (who also contributes to the vivid soundtrack), Kate McKinnon (as “Weird Barbie,” the victim of an overly playful child), and transgender actor Hari Nef. In this Barbie Land, inclusiveness matters–a perspective clearly borrowed from Gerwig’s view of the real world.

The Kens include Simu Liu, Kingsley Ben-Adir and John Cena, each of them either playing heightened versions of their screen personas or amusingly against type. Michael Cera portrays Allan, a character who seems out of place with both the Kens and the Barbies. His terse dialogue speaks volumes.

Barbie is a visual feast. The stylized sets align with the doll and the classic accessories. We’re meant to appreciate the artifice; Gerwig could easily have added Federico Fellini’s Amarcord to her list of influences. The main characters, especially Barbie, often move like toys, and Gerwig manipulates them in ways that generations of children (and some adults) have. High marks to cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto (Brokeback Mountain, Argo, The Wolf of Wall Street) and the Production Design and Art Direction teams, led by Sarah Greenwood (Beauty and the Beast, Sherlock Holmes).

Perhaps inevitably given the subject matter, Barbie descends into silliness at times. And Ken–much more than “just Ken”– almost steals the show. But Gerwig, in her roles as co-writer and director, does a remarkably good job of calibrating all of the elements and messages in the film. It’s sly, subversive and relevant. After more than sixty years, Barbie the cultural icon really is timeless, as well as enigmatic.

More Movie Reviews:

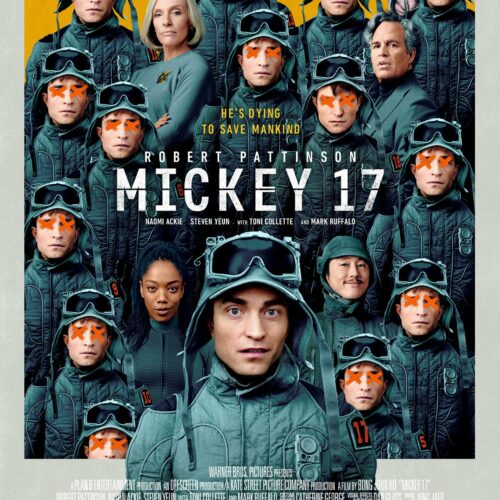

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Mickey 17

Movie poster of Mickey 17 courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures. Read “You don’t look like you’re printed out. You’re just a person.” In writer-director Bong Joon Ho’s new science fiction

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: A Complete Unknown

In director James Mangold’s new film, Timothée Chalamet portrays the young Bob Dylan (the professional name he adopted at age 21) from 1961-1965. He gives a remarkably nuanced, accomplished performance in a movie that occasionally gets bogged down in truncated or unnecessary scenes, but not too often. The supporting cast shines as well.

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Nosferatu

A classic tale laced with horrific, religious, folkloric and erotic themes. Robert Eggers seemed destined to make a movie about it. Finally, after a decade of preparation, he has.