‘It’s going to take all of us’: Yakama Nation youth learn about Hanford’s legacy

Listen

(Runtime 4:00)

Read

On a warm evening last month, Yakama Nation leaders and environmentalists got together to eat giant crab legs, salmon and cheesecake – and to discuss the grave environmental challenges before them at Hanford.

In a banquet room, past the whirring machines at the back of Legends Casino in Toppenish, Washington, they talked for hours about the site and its radioactive contamination.

“When I think about being able to speak for the resources, for those not yet born, I think about the people in this room,” said Emily Washines, board president of the watchdog group Columbia Riverkeeper and a member of the Yakama Nation.

“I think about the messages that we carry,” she said. “The messages that we give to our children and even other youth in the community, about what we have to do. Because it’s going to take all of us in order to make and restore this area and land again.”

Long before the U.S. government made plutonium for nuclear bombs at the Hanford Site in Washington, the land belonged to Native peoples. For the Yakama Nation, the area was vital for hunting and fishing for centuries. Now, it’s largely contaminated by radioactive waste.

In all, there are four tribal nations displaced and affected by Hanford’s mission and contamination. Yakama Nation adults have visited the cleanup site many times. But in May, with help from Columbia Riverkeeper, they organized a trip for high school and college students.

“For them to see it and understand,” said Phil Rigdon, superintendent of the Yakama Nation’s Natural Resources Department. “And then also to see what this sacred place – what’s happened to it. And the devastation that’s happened because of the nuclear reservation and how that fits, and that they are going to be responsible to the future of carrying on what we’re trying to do.”

Properly treating the radioactive waste at the site could cost more than $500 billion. The U.S. government has been trying to settle on a cleanup plan for decades.

But Rigdon says it’s not just a cleanup site. It’s their ancestral land. People lived here. They sang songs – many of the same ones sung today.

The Columbia River sweeps through the site: That’s where they caught salmon. People gathered roots and medicines, conducted ceremonies and buried their dead.

A “No Trespassing” sign guards Rattlesnake Mountain, named “Laliik” by the Yakama Nation. Recently, about 70 high school and college students from the nation toured the Hanford radioactive cleanup site, which is part of their homeland or tiicham. (Credit: Annie Warren / NWPB)

Homeland bus tour

After months of planning and paperwork, a group of nearly 70 students got to see the site by bus.

The students learned about the heavy pollution, left over from producing plutonium during World War II and the Cold War. That includes 56 million gallons of radioactive sludge, stewing in aging, underground tanks near the Columbia River.

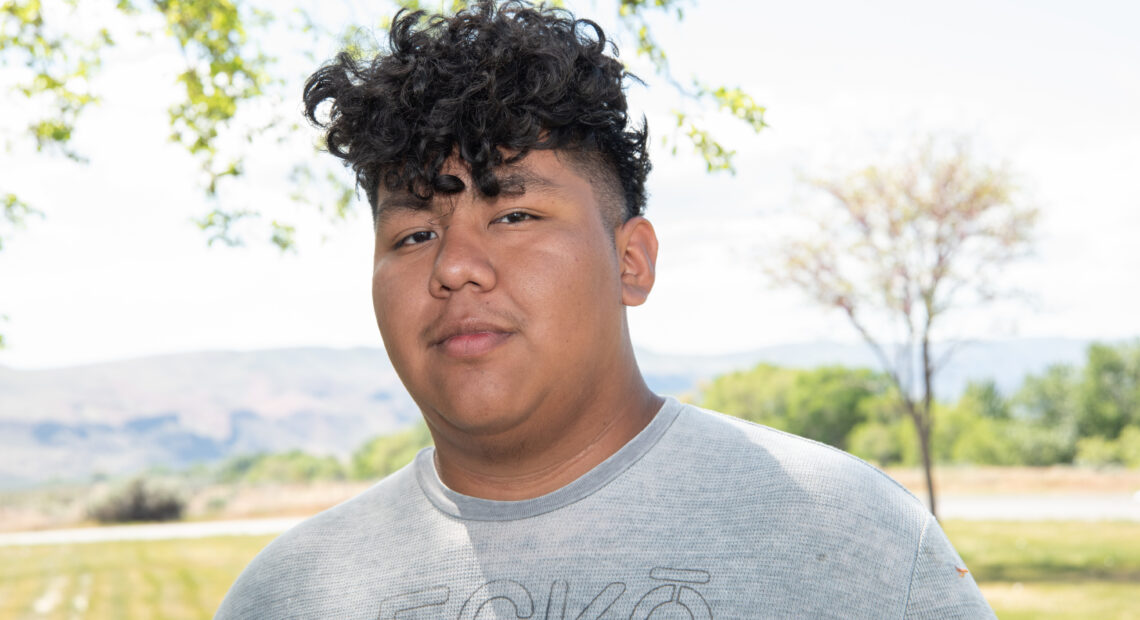

“I got to see the tanks, the reactors — all different nine reactors — we got to drive by, and we obviously got to go in Reactor B,” Leilani Redheart said.

Redheart, 17, said she’s visited Hanford before with some of the adults. But for a lot of the kids, it was their first time here.

“It’s okay what they feel, just as long as they know about Hanford,” Redheart said.

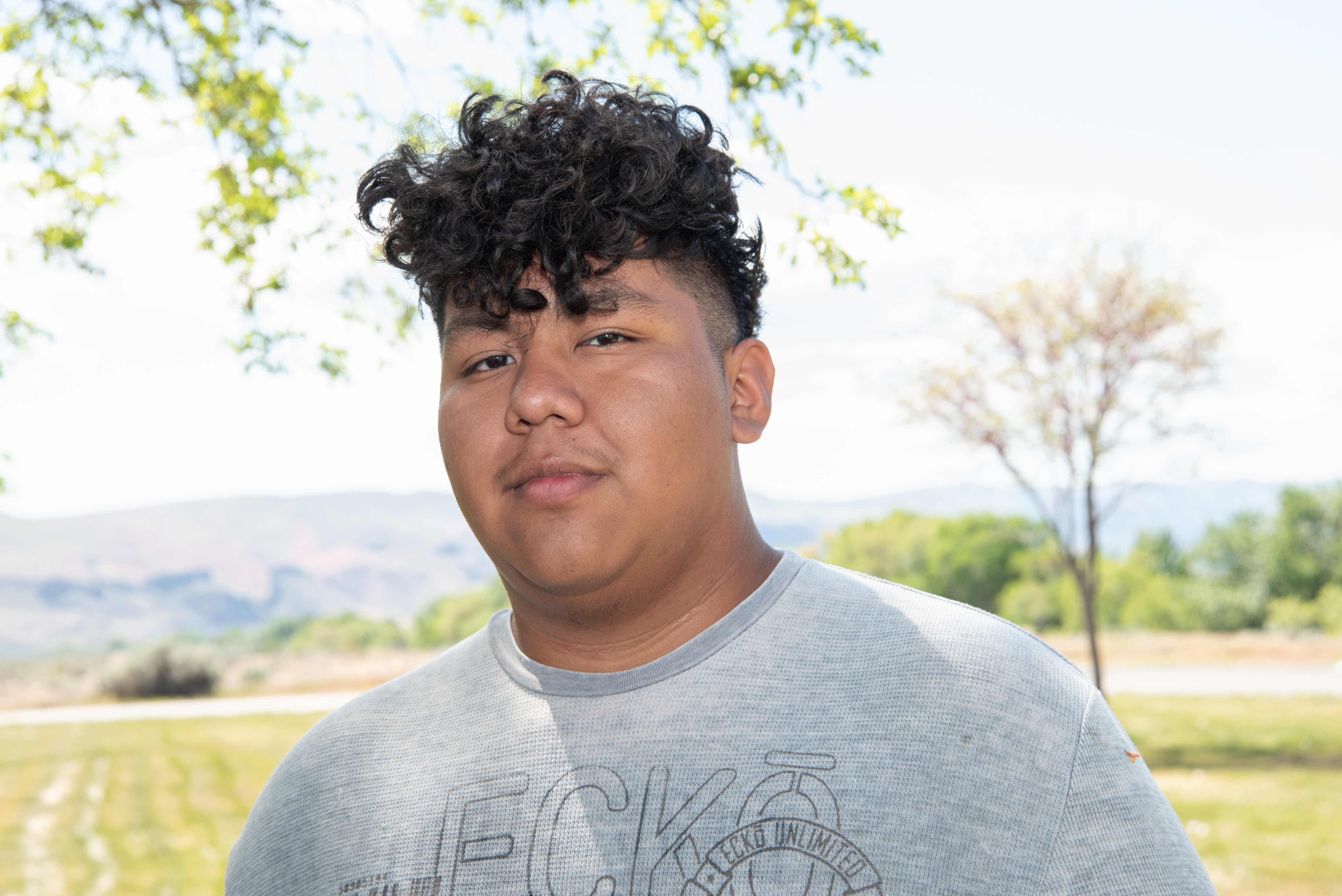

Jordan Ashue, 18, said he was surprised when he learned how long the clean up will take.

“There’s this specific thing where he was like, ’75 years just waiting to make sure it was good to clear out,’” Ashue said, referring to one of the cocooned reactors. “That sounds like awhile. What am I, 18? [I’m] gonna be like 90 years old. That’s gonna be awhile.”

The bigger picture is that Hanford’s radioactive waste will remain hazardous for many generations.

Leilani Redheart, 17, has visited Hanford with adults before. But she says she was happy to return with students her own age to learn about the tank waste at the site and the historically-significant B Reactor. (Credit: Annie Warren / NWPB)

Healing the land

“For as long as I can remember in my life, my grandfather taught me that we are the stewards of the land,” said Jon Shellenberger, an enrolled member of the Yakama Nation and an archaeologist.

“We still will always have that responsibility. And true, it may not be cleaned up in 5,000 years or 500 years or 50,000 years, but that responsibility will always be ours,” Shellenberger said.

Phil Rigdon, with Yakama Nation’s Natural Resources, said even this brief visit is packed with meaning.

“The presence of our people, even if it is for a short period – if we are able to sing a song, if we are able to be in the land – it knows us. It knows who we are.”

It’s hard to impart centuries of knowledge of this landscape in a single day, he said, but even just a little bit helps the land and the people heal.