Could the Northwest’s basalt rocks help slow climate change?

Listen

(Runtime 3:53)

Read

On the banks of the Columbia River, tall columns of rock poke out from the cliffs.

“So you see all of these black rocks that are on either side of us, on either side of the river? Those are basalts. And they’re volcanic rocks that erupted about 15.5 million years ago,” said Casie Davidson, a geologist with Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

As the lava cooled, she said, gasses got trapped in the porous rocks. That created cavities in the rocks. Another solid layer of rock later cooled on top of the porous one. Layers piled on top of layers.

Casie Davidson holds two basalt rocks together to show how the rocks are layered on top of each other. (Credit: Ashley Montes / NWPB)

Today, Davidson and her colleagues say those cavities can be used to trap carbon dioxide — in a process called carbon sequestration.

“Can you imagine what it looked like here with these volcanoes erupting and this massive amount of lava flowing through here? Can you imagine what the climate was like? And it was probably terrible to breathe,” said Todd Schaef, a geologist at the lab. “There’s no telling how much crap was in the air. And now we’re asking the same formation to help us.”

Carbon sequestration isn’t new. Places in the Midwest and Gulf Coast already store carbon underground like this in sandstone rocks.

But, basalt is different. When you put CO2 in the spaces between the rock, it turns into minerals.

“Once it’s mineralized, the really cool thing is it can’t leak. It is a solid rock. It’s not going anywhere,” Davidson said.

Some of the best basalt formations are in the Northwest. But this type of carbon sequestration hasn’t been studied here until recently. In fact, the only test site in the world for storing carbon dioxide in basalt is just down the river from where the researchers stood.

At that site in 2013, scientists pumped liquid CO2 down a conical hole they drilled. It was more than a half-mile deep – about seven times the size of Palouse Falls. It took them more than three months to carefully drill and measure the rock.

“We are science nerds, and we always want more data. Drilling in the deepest part of the basin helps us get those data that we need,” Davidson said.

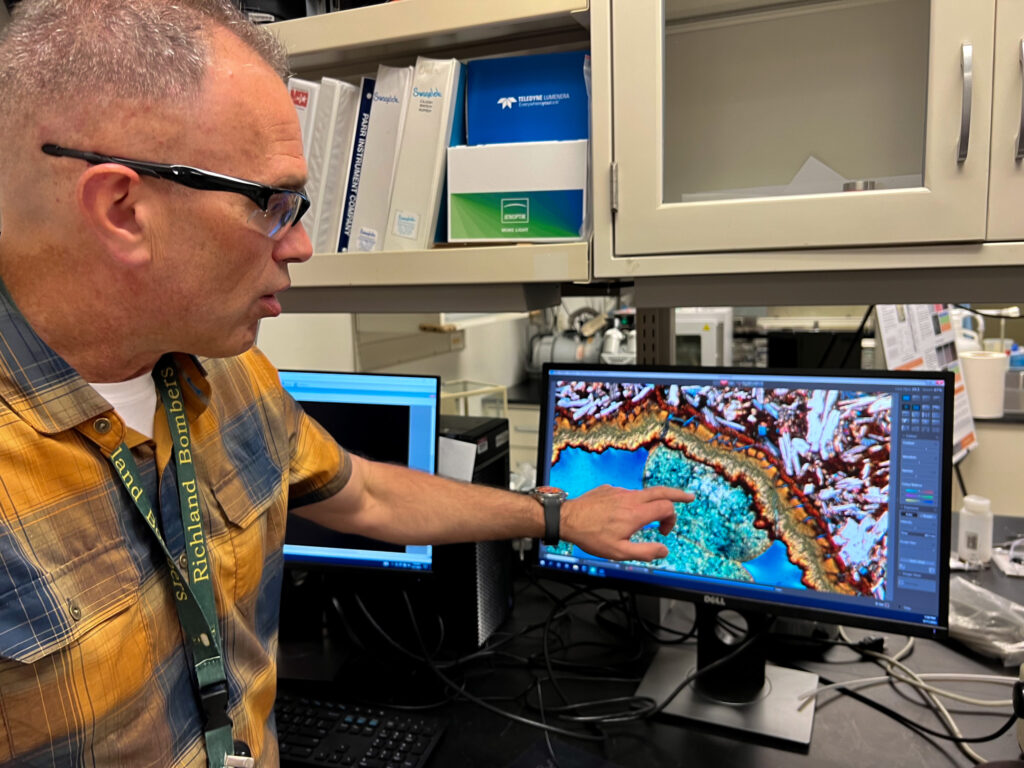

Scientist Todd Schaef points out what a thin layer of the basalt and mineralized CO2 look like under a microscope. (Credit: Courtney Flatt / NW News Network)

In just a couple years, the CO2 had started to transform into minerals. Good news, they said, to keep carbon out of the atmosphere. And that test site, Schaef said, wasn’t very deep underground.

“So we were really kind of at the very minimum. It only gets better after this,” he said.

In the Pacific Northwest, this kind of carbon capture and sequestration is still in the research phase – it’s not happening yet on a large scale. Davidson said it will be a Band-Aid as the region transitions to renewable energy. She said it’ll be especially useful for industries that produce a lot of CO2, like manufacturing plants.

“You’re going to have to put all of that somewhere. We want to do stuff with it as much as we can – convert it into things. But the vast majority of it will need to go in geologic reservoirs,” she said.

But, a lot of the geologic reservoirs in the Northwest’s basalt are in the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation’s homelands. There needs to be a better understanding of the mineralization process before this technology becomes widespread, said Althea Wolf, with the tribe’s Department of Natural Resources.

“We’re really worried about what this impact is going to be to the homeland because that’s what the Columbia Plateau is – it’s basalt,” Wolf said.

Wolf said the tribe worries that drilling deep into the earth could contaminate the groundwater.

Instead, she said, researchers should focus on low-tech solutions, like restoring forests. Wolf said forests can store carbon at tremendous rates. But holistic approaches get less attention and funding.

“So we have the potential but it’s not being supported as much,” Wolf said.

Basalt rocks line the Columbia River in southeastern Washington. (Credit: Ashley Montes / NWPB)

Pacific Northwest National Lab said storing CO2 in basalt will be one tool to sequester carbon. But, they want to be respectful of local tribes.

Schaef said if a proposed drill is on sacred land, or a place with ancestral importance, they’ll move the project.

“There’s a lot of basalt around here. So let’s start talking about: What are those sites that are very sacred and have ancestral importance? We don’t have to use those sites,” he said.

This summer, the team hopes to drill another test site a few minutes south, in Hermiston, Oregon. That site won’t inject any CO2. The goal is to help scientists better understand the area’s geology.

In an upcoming paper, they also plan to estimate the carbon storage potential in the Northwest.

“This is really just sort of putting basalts on the map as a significant CO2 storage capacity resource, particularly in this region,” Davidson said.