‘The Farewell Tour’ brings readers back in time to Tacoma’s honky-tonk history

Listen

(Runtime 3:26)

Read

While the West Coast is known for grunge and surf rock, Stephanie Clifford’s latest novel, a piece of historical fiction, reminds readers of the roots country music has here, especially Tacoma.

Tacoma, a burgeoning port city on Commencement Bay in the 1940s and ’50s, plays a central role in “The Farewell Tour.” The book is an American West tale of coming home, with a few forks in the road, that takes readers back in time over the protagonist’s life as she makes her way as a musician on the West Coast.

The book also explores the effects of racism and sexism at the time.

When writing the book, Clifford said she was aiming for a different kind of western.

“When I read novels of the American West, they were all set in Arizona, California, these really dry, barren landscapes and weren’t about this lush Northwest we know,” Clifford said.

Clifford wanted her story to grapple with the history of Washington state, one that is as lush and varied as its 71,300 square-miles of topography. The main character, Lillian Waters, traverses the state through the early years of her life. She is born on farmland in Walla Walla, then heads west on the train for Tacoma, the City of Destiny, where the smell of the port and the sounds of electric guitar beckon her in.

The book moves from Lillian’s present day in the ’80s, to flashbacks over her 50-some years. In 1980, she’s a middle-aged country music star on her final tour that’s set to end in Walla Walla. It’s the first time she’s going back to the home she left as a child, and the novel focuses on the character’s reflections from her life and career.

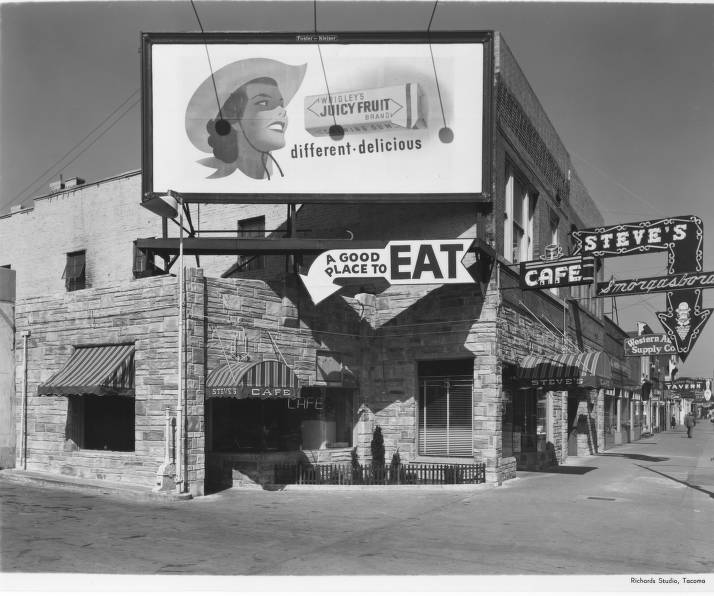

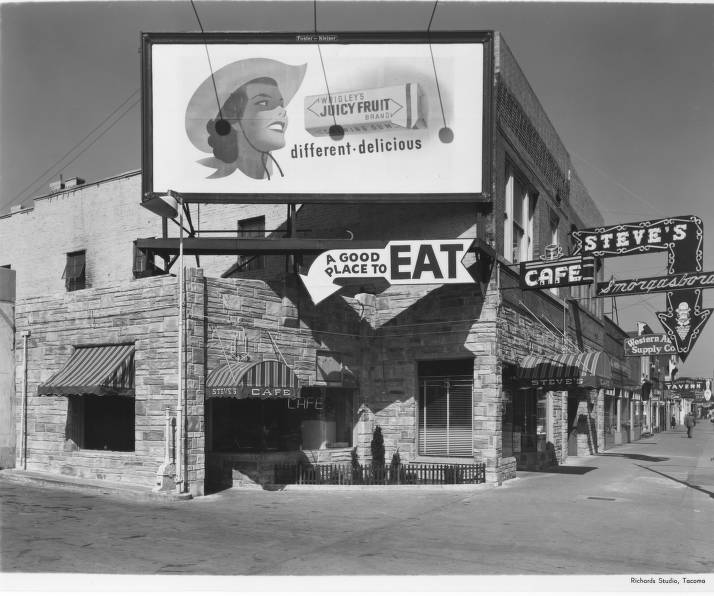

Tacoma originated rock group The Ventures, whose lead guitarist Nokie Edwards first played with country performer Buck Owens. Photo courtesy of the Northwest Room at The Tacoma Public Library,

Richards Studio D126221-14.

Tacoma’s honky-tonk history

Clifford said she played around with various careers for Lillian, knowing she wanted to set her life within pivotal, historical moments of the 20th century, such as the Great Depression, World War II and John F. Kennedy’s assassination. Then she discovered Tacoma had a thriving country music scene in the 1950s, and she said she felt it was the perfect fit for Lillian to be a songwriter and musician.

That might come as a shock to some Pacific Northwesterners, explained Kim Davenport, who runs the Tacoma Music History blog and is the communications manager for the Tacoma Historical Society.

“It’s somewhat counterintuitive because I think we tend to think of country music being based primarily in the South, and specifically, Nashville,” Davenport said.

But, the West Coast did have its own roaring country music scene, the center of which was in Bakersfield, California, where studios were creating the Bakersfield sound.

A little farther north, Tacoma was an epicenter of music and culture. The railroad ran through the city’s downtown, making it an easy stop for performers, who filled the big theaters of the time. Tacoma was also early to get into television. KTNT was transmitted from a building in the Hilltop neighborhood and had a number of country music programs. That’s where Arkansas’ coal miner’s daughter, Loretta Lynn, was discovered.

According to Davenport’s blog, in 1960, lumber baron Norman Burley heard Lynn sing on one of the country music shows and invited her to record for his label. Buck Owens, a country musician from California, came to Washington and hosted country music shows on KTNT. He also ran a radio station in Puyallup called KAYE that played country music. Owens became musical partners with electric guitarist Don Rich, who he met in Tacoma.

So even though most people think of Nashville as the heart of country music, the West Coast was creating its own sound. Nashville’s country sound was also evolving post-World War II. There was more studio production and the addition of instruments, such as violin and piano, Davenport said, whereas the West Coast sound was closer to country music’s roots.

“There are a handful of pictures of country music being made in Tacoma, and it’s what you would [expect],” Davenport said. “It’s kind of the stereotypical guitars and fiddles, that kind of roots-based country music.”

That’s something Clifford picked up on for her novel.

“The Tacoma sound was really a different sound than what was coming out of Nashville,” Clifford said. “Nashville at the time was violins and choruses and very sweet and kind of a little overdone, and the Tacoma sound is for working people who are done with their work day and want to go to a honky tonk and dance and drink some beer.”

Electric guitar, backslapping rhythm, Clifford said the music was fun and wild and fast, and it’s the kind of music her protagonist loves and learns to play.

The difference between Washington’s country music scene and Nashville’s, where commercial success abounds, gives Lillian a chip on her shoulder as she explores the new sound coming out of Tacoma.

She struggles throughout the novel as a female songwriter and musician, competing with the commercial success of the Nashville sound, and the image record labels want to paint of her as a doting, traditional housewife, when she just wants to play her electric guitar.

“She’s got to be this country songwriter, who’s not only trying to forge a way as a woman, in this time, but in this like, incredibly male-dominated industry, trying to figure out what kind of songs she can even sell, what kind of songs she can sing, how she has to package herself in order to succeed,” Clifford said.

The odds are stacked against Lillian from the patriarchal structures of society and her personal, abusive relationships.

Writing historical fiction from a west-coast lens

Like her protagonist, Clifford is from Washington but moved away. She now lives in Brooklyn, but she wrote this book from her roots in the west, a region that has a long record of providing fruitful soil for writers’ seeds to grow: Willa Cather, Joan Didion, Cormac McCarthy.

“I think the landscape is so stunning and wild that it’s hard not to be inspired by it,” Clifford said.

Clifford also centers the novel on historical moments that represent the nation’s fraught past. In 1942, Lillian watches her Japanese-American neighbors forcibly sent to internment camps. She witnesses the racism her Black coworker Althea faces as the two form a four-piece all-female band while men are away fighting in World War II. When she visits Althea years later, she learns how she and her husband were redlined, hindering their economic growth. Redlining was a historic and racist practice where the government pushed communities of color out of certain neighborhoods and into areas where services were withheld.

Lillian is passive and even harmfully ignorant, to the racism happening in Tacoma. She doesn’t intervene in the racism around her because, even through her own struggles, she is part of the racist system.

It isn’t until the 1980s, when her young fiddle player, Kaori, forces Lillian to confront her inaction that she realizes the harm she has caused.

Clifford said, in some ways the West has gotten away with pretending it doesn’t have “those problems,” when compared to the South. But the West’s history of things such as internment and redlining continue to shape inequality today.