Captains of big ships eased up on the throttle during trial slowdown to help endangered orcas

Read

The majority of captains of big commercial ships entering and leaving Puget Sound are cooperating with a request to slow down temporarily to reduce underwater noise impacts to the Pacific Northwest’s critically endangered killer whales. The duration of the experimental slowdown – modeled on a similar project in British Columbia – will be extended into the new year, organizers announced after a status report and celebration on the Seattle waterfront Friday.

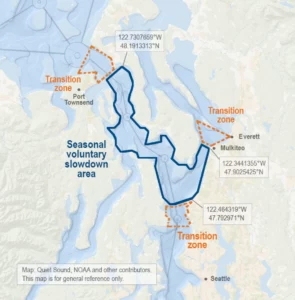

The voluntary slowdown for container ships, tankers, freighters, cruise ships and car carriers began October 24 and was scheduled to run through December 22. The slowdown area covers the shipping lanes from Admiralty Inlet by Port Townsend south to Kingston and Mukilteo. It will now run until January 12, largely due to the delayed deployment of an underwater noise monitor which will be used as part of the project evaluation.

A relatively new, government-funded outfit named Quiet Sound organized this trial run. Program director Rachel Aronson said she is very pleased by the initial participation rate.

“So far, we’ve seen that 61% of vessels are slowing down for their time passing through the slowdown area at the north end of Puget Sound,” Aronson said. “And whales have been present in the slowdown area for a little over half of the days of the slowdown.”

The population of resident killer whales in the transboundary waters of the U.S. Pacific Northwest and southwestern British Columbia has dwindled to 73 individuals. These orcas primarily use sound — including echolocation — to hunt for food, orient and communicate. Ship noise can mask the whale calls, effectively blinding the mammals, whose ears in a lot of ways act as their eyes.

Canadian and American government agencies have identified physical and acoustic disturbance as one of the key threats to survival of the fish-eating killer whales, along with lack of prey and water pollution.

Map of 2022 Admiralty Inlet and North Puget Sound voluntary vessel slowdown area. Credit: Quiet Sound

Aronson said the time period and geographic area for the trial slowdown were chosen because historically the iconic orcas venture into inland Puget Sound during that window to chase autumn and early winter salmon runs. By coincidence, a pod of 16 to 30 widely spaced, foraging orcas swam past Seattle while Aronson, Washington Gov. Jay Inslee and port officials spoke on the waterfront about endangered orca recovery efforts. The whales, though, could not be seen from the indoor hall at the Seattle Aquarium where the bigwigs gathered.

Shipping lines willing to go along when they can

The Quiet Sound program asked container ships, cruise ships and vehicle carriers to go 14.5 knots or less through the slowdown zone, when safe to do so. Tankers and bulkers were asked to go 11 knots or less. Washington State Ferries opted out of participating to maintain its tight schedules, though ferries routinely slow or change course if whales are in sight.

Captain Mike Moore, vice president of the Pacific Merchant Shipping Association in its Seattle office, said his member companies were willing to do their part for environmental stewardship.

Moore said complying with the slowdown was “not typically” an imposition. “But if you’re really running behind on your schedule and you’ve got to get to the dock, and the labor gang is going to be there, that could be a little more sensitive.”

Moore added that it could be a “difficult scientific challenge” to figure out if the underwater noise reduction effort provided a meaningful benefit to the endangered orcas. After all, you can’t ask the killer whales directly if the vessel slowdown proved worthwhile.

“Right now, we’re just going to have to settle on the fact that we’re going to measure noise reduction and hope that it’s helping,” Moore said. “But ultimately, the question is how do you measure actual benefit? Maybe it’s a longer trend, longer timeline, that is necessary to pull in the right data to answer that question.”

Aronson said a key factor behind the good participation rate of vessels in the trial slowdown was the support of the Puget Sound Pilots, who board tankers and foreign ships and guide them in and out of Puget Sound ports.

During a recent ride-along on a big container ship outbound from the Port of Seattle, the influence of the local pilot was clear. Prior to casting off, Puget Sound Pilot Jostein Kalvoy briefed the South Korean captain, J. Yun, on the bridge of the SM Yantian.

“When we go out tonight, we have a trial, voluntary slowdown for the orca whales,” Captain Kalvoy explained to Captain Yun. “We will adjust our speed down to 14.5 knots or less. That’s OK for you?”

“Yes,” nodded Yun, who was hearing about the slowdown zone for the first time.

Afterwards, Kalvoy estimated the slowdown cost the 1,000-foot container ship about 30 minutes. The ship’s normal cruising speed is around 18 knots. The big vessel later made up for some of the lost time by catching a strong outgoing tide.

Inspired by Canada’s’ success nearby

The model for the Quiet Sound trial run came from a now six-year-old voluntary seasonal slowdown for large ships in the nearby U.S.-Canada border waters. The Vancouver Fraser Port Authority spearheaded what is known as the ECHO Program to reduce disturbance to endangered resident orcas in their prime summer feeding grounds. This slowdown zone covers the busy shipping lanes in Haro Strait and Boundary Pass adjacent to San Juan Island. In 2020, the project expanded to establish another slowdown zone across Swiftsure Bank, an orca foraging area at the western entrance to the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

A season-end report from the ECHO Program emailed on November 17 touted record-breaking participation rates in the underwater noise reduction initiatives during 2022. Program managers wrote that 93% of commercial ships slowed down in Haro Strait and Boundary Pass and 82% of ships did so at Swiftsure Bank.

The 61% participation rate reported by Quiet Sound during the first four weeks of the Puget Sound trial slowdown is about the same as what the ECHO Program experienced during its first year. Aronson said she expects the participation rate on the U.S. side to go up in future years as the masters of ships become familiar with the Quiet Sound project.

Aronson said she is pretty sure the Puget Sound slowdown will be renewed for a second season in fall 2023. But before that happens, a panel of maritime industry, environmental, tribal and government agency representatives will review the track record of the first year and suggest any desired changes.