Federal report recommends removing four lower snake river dams to protect salmon

Read

Breaching the Snake River dams is one major way to protect salmon, according to a final federal report announced Friday on salmon and steelhead recovery in the Columbia River Basin.

“The common message is clear across all the work: salmon rebuilding depends on large-scale actions, including breaching dams, systematically restoring tributary and estuary habitats, and securing a more functional salmon ocean ecosystem,” according to the report.

This report from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which manages salmon recovery, could have big implications for the fate of the four controversial dams in southeastern Washington, conservation groups said.

Removing the four Lower Snake River dams is the foundation of salmon recovery measures in the Columbia Basin, said Rob Masonis, Trout Unlimited’s vice president of Western conservation.

“If you don’t have that foundation, the billions of dollars that we have spent, and will spend in the future, will not produce the desired outcome of salmon recovery,” Masonis said. “We need to remove the big bottleneck that’s preventing us from realizing the benefit of those investments and that’s the four dams on the Lower Snake River.”

However, U.S. Rep. Dan Newhouse, R-Washington, said the report ignored the opinions of most people in the Columbia Basin.

“The Biden administration is playing politics with its energy future, while ignoring recent data showing spring and summer chinook returns at higher levels than they have been in years,” Newhouse said in a statement today.

The four Lower Snake River dams provide carbon-free energy to the Northwest. In addition, the four dams allow farmers along the river to irrigate crops and barges to reach the inland Port of Lewiston. Washington Gov. Jay Inslee and U.S. Sen. Patty Murray, both Democrats, have said these services need to be replaced before the dams can be removed.

However, removing the dams would lead to one of the best chances for salmon recovery, according to the report, especially in the face of a changing climate, which will continue to increase water temperatures and decrease river flows important to salmon survival.

In other cases where dams have recently been removed, such as on Washington’s Elwha and White Salmon rivers, river ecosystems improved faster than expected, according to the report.

In the Columbia Basin, the biggest challenges to salmon and steelhead outlined in the report included climate change; degrading tributary and estuary habitat; the hydrosystem; predation from penipeds, native and non-native fish, and colony-nesting waterbirds; and other barriers built by people, such as culverts.

The report outlined mid-range goals for wild salmon and steelhead numbers by 2050 set by the Columbia Basin Partnership task force, which included tribes, agriculture, fishing, and transportation groups.

The task force suggested recovery goals that would reach beyond removing salmon and steelhead from the Endangered Species List, instead aiming for what the task force called healthy and harvestable populations.

The mid-range goals show that the fish would not reach healthy and harvestable populations. Mid-range goals would be on the path to healthy and harvestable populations, which the report called “a substantially more ambitious goal than meeting Endangered Species Act recovery standards.”

To reach these mid-range numbers of salmon, the report identified several core actions, which it indicated would make the best progress in recovering salmon and steelhead in the region. Those actions include breaching the Snake River dams; managing predator numbers; restoring and protecting tributary and estuary habitat and water quality; adding fish passage to the Upper Columbia River, which is blocked by Chief Joseph and Grand Coulee dams; and implementing harvest and hatchery reforms.

All of the actions must happen quickly and on a large scale, according to the report.

Breaching the Snake River dams would help young fish move faster downstream, according to the report. It would reduce the number of dams the fish must encounter as they head to the ocean, which would reduce stress for juvenile salmon. It’s uncertain, but that additional stress may lead to more of these young salmon dying in the ocean, according to the report. In addition, breaching the dams would create more rearing and spawning habitat.

Moreover, reintroducing fish above Chief Joseph and Grand Coulee dams and establishing adult and juvenile fish passage into the Upper Columbia River would buffer populations against climate change, according to the report. It would provide access to more productive spawning grounds. In addition, it would benefit other species as salmon are reintroduced above the two dams.

“This is a crucial time for the Columbia Basin’s salmon and steelhead. They face increasing pressure from climate change and other longstanding stressors, including water quality and fish blockages caused by dams,” said Janet Coit, assistant administrator for NOAA Fisheries and acting assistant secretary of commerce for oceans and atmosphere at NOAA.

Climate change will deteriorate ocean and freshwater conditions, which is why it’s important to improve conditions that are more directly impacted by people, according to the report.

To buffer against climate change, the report recommended maintaining low water temperatures and appropriate water flows for fish, including adjusting water flows for fish. In addition, to help salmon survival during periods of poor ocean conditions, the report recommended increasing salmon survival and spawning in freshwater habitats. Moreover, the report recommended maintaining and restoring access to habitat that’s more climate resilient because it’s in areas of high-elevation or connected floodplains.

If all of these actions are done, salmon and steelhead should see numbers improve, according to the report.

In all, the report looked at 16 salmon and steelhead runs that spawn upstream of the Bonneville Dam on the Lower Columbia River.

The report didn’t consider funding sources, regulations needed for implementation, or impacts of the recovery measures, including dam removal. Instead, the actions outlined in the report should help inform other dam removal discussions, according to the report.

To figure out which salmon and steelhead needed the most help right away, the report analyzed several criteria, which weighed the extinction risk with the ability to rebuild as the climate changes. Another key factor included the importance to tribal communities.

The highest priority runs included Snake River spring/summer chinook salmon, Snake River steelhead, Upper Columbia River spring chinook salmon, and Upper Columbia steelhead, according to the report. These stocks of salmon make up earlier recreational fisheries and tribal subsistence and ceremonial harvests.

Other prioritized stocks included Upper Columbia fall chinook salmon and Upper Columbia summer chinook salmon. Although these salmon are not listed on the Endangered Species Act, they are important for tribal harvest and recreational and commercial fishing, according to the report. In addition, tribal reintroduction efforts above Chief Joseph and Grand Coulee dams rely on Upper Columbia summer chinook salmon. Salmon haven’t reached the Upper Columbia River since the dams were built.

Related Stories:

Snake River water, recreation studies look at the river’s future

People listen to an introductory presentation on the water supply study findings at an open house-style meeting in Pasco. After they listened to the presentation, they could look at posters

This transfer will help Grand Coulee Dam run more efficiently, save money

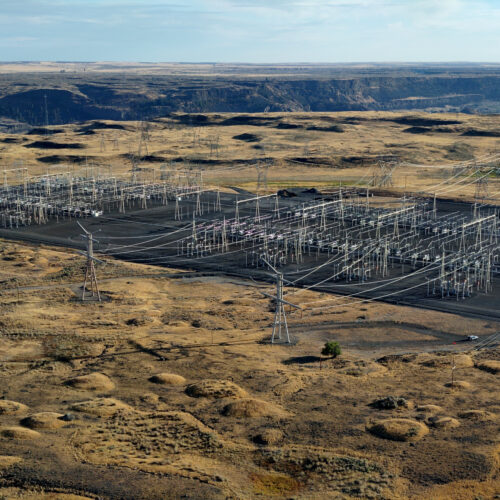

One of the electrical switchyards at Grand Coulee Dam. (Credit: Bureau of Reclamation) Listen (Runtime 0:56) Read There’s a transfer happening at Grand Coulee Dam. After years of planning, the

Decision upheld to remove a portion of Electron Dam on the Puyallup River

A portion of the Electron Dam on the Puyallup River has to be removed, according to a decision from the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

The federal appeals court upheld the decision by the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington that a vertical metal wall portion of the dam, a temporary spillway, makes the dam a complete barrier to fish passage and must be removed.