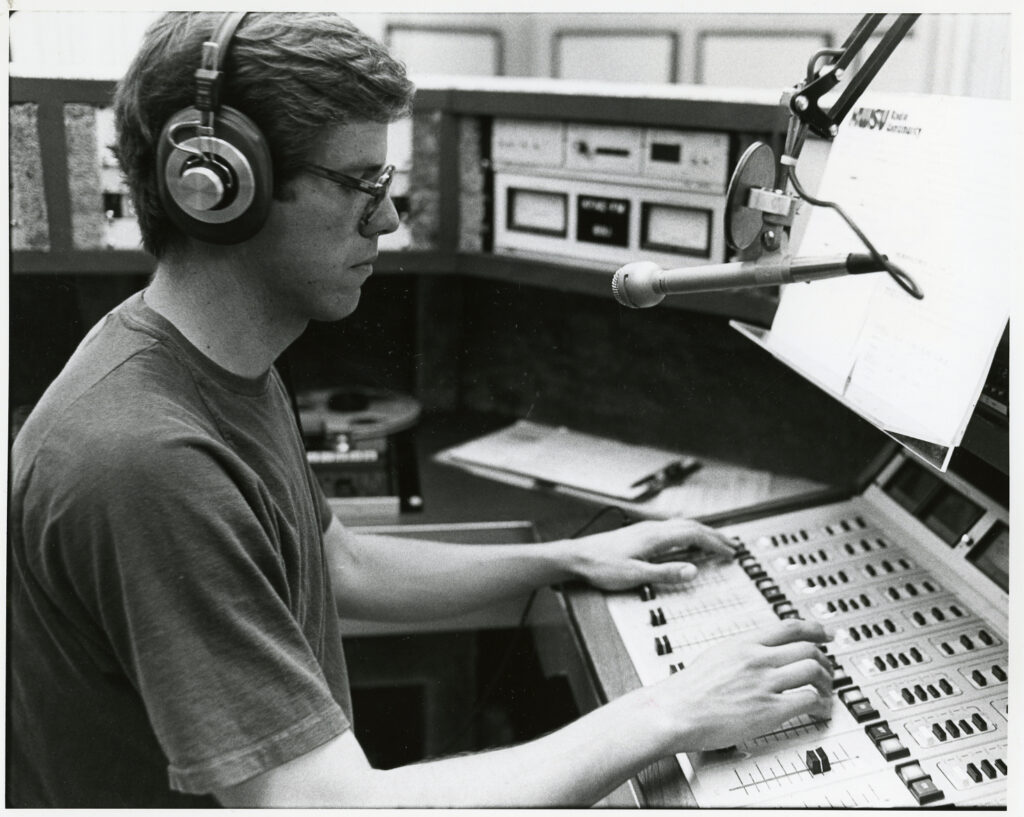

Bill Morelock

Former On -Air Personality

Starting as an English major at WSU, Bill Morelock slowly but surely made his way to KWSU-TV and then by 1985 he ended up in the realm of radio. Alongside the Program Director Bob Christiansen, the two created a classical music talk show. The Bob & Bill Show became a national success distributed by NPR and PRI until the 90s. Bill still occasionally makes appearances on-air at NWPB.

"We wanted to talk about classical music like two friends talking about baseball."

Summary:

Here Bill talks with Host/ Producer Thom Kokenge about the unlikely start of the Bob & Bill show and how their idea to “talk about classical music like two friends talking about baseball” was quite revolutionary at the time… and definitely not well received at first.

[Thom] I’m Thom Kokenge, and I’m talking to Bill Morelock. And so why don’t you talk about a little bit, how you started with Northwest Public Broadcasting, how that came about?

[Bill] I was an undergraduate at Washington State. I went away for a couple of years and worked a lot of menial jobs. I shined shoes and cleaned toilets. And at 24, I thought, “Oh, I really have to do something responsible.” So I applied to graduate school.

[Thom] At Washington State University.

[Bill] Yeah, in the English department. And after a year, I wandered from Avery over to Murrow. And they needed bodies in radio. And so on Christmas Eve 1981, I did my first shift. Somebody needed to be filled in for. And the training amounted to, “Okay. Sit down. Do it.” For the next few years, I was a classical music announcer of sorts. I was able to be bad without many people noticing for several years until I finally got some sense of how to do this. But it was great. And then in 1987, they hired a new music director. I remember very vividly Arthur Cohen, who was my boss, played me the tapes of the people who had applied.

Bill Morelock (left) and Bob Christiansen (right) pose for a photo in the spring of 1994.

There was one in particular, I said, “Oh, I don’t want that guy. He sounds just this old school, very dignified kind of thing.” And Arthur said, “Well, his name’s Bob Christiansen and I really like him.” So Bob came and very quickly hit it off. And I discovered in him something that was new to me. You run into people who are wits, but sometimes they can use their wit for evil. And Bob’s wit was kind and benign. And we started doing a handoff promo between the morning shift, mine, and his afternoon shift. And we hatched an idea to do a two-man classical music show. We wanted to talk about classical music like two friends talking about baseball.

We own stuff in popular culture and in the sports landscape, if you’re into that, in a way that we don’t own it in classical music because it’s so towering with all these various classifications and levels of technical minutia that may or may not be important in a radio broadcast, but they’re there. And it’s intimidating because your listener might be expecting that analysis of a score. And we are not going to give you that. We’re going to give you stories about the composers or place the music in a historical timeframe, something to make it vivid. We tried it in, I guess, January of 1988, and we got absolutely no happy mail for three or four months. One I remember very clearly was a woman in Palouse. She likened us to two pre-adolescents out behind the barn, smoking cigarettes and telling dirty jokes. I actually grew a skin that day because I had a very thin skin.

And I think every person who does classical music broadcasting when they’re new understands that listeners are very particular, bordering on hostile if you make a certain mistake, and they will say, “You are representative of the downfall of Western civilization.” The comments are like that. It’s a very strange world. But I did realize that what we were doing, we were taking away a self-conscious consumption of culture for people because the sound of classical music broadcasting, you entered into this sanctum somehow. So we learned from that.

Caricature sketch of Bob Christiansen and Bill Morelock.

We learned that when you try to do something different that you really want to do, you may have to feel these kinds of things and absorb them. And I think over time, people trusted us that we weren’t punks and we weren’t trying to destroy anything and that we loved the music. So it was just a different way of doing it. And it was satisfying to have somebody to bounce things off of.

"There's a way of doing this that's really about storytelling and then the music takes over."

Summary:

If you have been a fan of classical music on NWPB for a while, you might remember the Bob & Bill show. The show was nationally distributed on NPR and PRI until the 90s. In this interview with Thom Kokenge, listen to classical music host Bill Morelock explain how the show became a national success and what it meant to him. Also, hear Bill discuss what it was like to work in radio in the 80s and how the Gulf War forever altered the standards for a radio show.

[Thom] You and Bob created this show that became a national show.

[Bill] Right.

[Thom] What were you doing that was part of the zeitgeist that created this?

[Bill] It actually wasn’t so much a zeitgeist as one individual that NPR who thought this had some potential. He got in touch and said we’d like to think about syndicating this, but he said, “Every day you make me a movie, and I come for the movie and I stay for the music, and I think that’s why it could work.”

I liked that because for Bob and me and for you and for everybody here really, what we should serve is radio. That’s our medium, and we happen to be using this music which we happen to really love and has the potential to make an incredibly rich tapestry and great radio because of the way the music can naturally connect with all the other arts.

We didn’t have to be that obviously or overtly reverential about the music. If the show was successful and people listened, they were getting the music. We didn’t have to be constantly genuflecting to it. You can bounce around. If you get the right stories, it connects with everything. It really does.

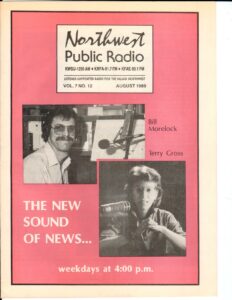

Bill Morelock accompanies Terry Gross on the front page of a NWPR bulletin from August 1989.

I mean, there’s a way of doing this, that is, really about storytelling, and then the music takes over because the storytelling is what we contribute to it, and the music is a fait accompli. It’s there, we play a recording. That was kind of the ferment of it, I guess.

[Thom] It actually went to NPR and they distributed it?

[Bill] Back then just before All Things Considered was over, I would walk over to the wall and start the tape, and then walk back and start our show. ANd then we’d collect five days of these tapes and then FedEx them to DC, and so we had to start early before the launch date, like six weeks early so that we could make sure that we have had enough tapes.

They started airing them the 1st of January, and then the darnedest thing happened, the Gulf War, 1991. So we get a call saying that you have to go into the studio now and record a show with the proper tone for what’s happening, and they wanted us to include a four minute news window. This was absolutely new for a music program, and so we had to dump six weeks of programming.

[Thom] Oh man. And that’s standard now where we have a one minute billboard and then they break for five minutes or so, and then the program starts. So you started basically back in ’81, is that?

[Bill] Yeah, it was the end of ’81.

[Thom] So how much has the tech advanced?

[Bill] We played all records, of course, record LPs. We got our first CD in 1985. I remember that it was a Wagner CD with the Seattle Symphony. Announcers used to be responsible for recording programs off the satellite on open reel, which was a physical chore.

[Thom] A reel-to-reel.

[Bill] The reel-to-reel tape decks that were on a bank. The tapes would fire when the satellite sent the programs automatically, but you had to have the tape up.

One time when I was doing a shift, I had to record one of the Bach Passions, I think was the St. Matthew Passion. It was very long work, took two complete reels, at least I thought. It turns out there was a third reel and it came to be broadcast on Easter, and at the end of the second reel, it just ended, and there was nothing else.

I did that. That was mine. If you remember, St. Matthew Passion sometime in the early ’80s or mid ’80s, that was me. People were not pleased understandably so.

[Thom] The magic of radio.

[Bill] Yeah.