Two tailings dams that secure waste from a British Columbia mine 25 miles north of the Washington border have up to a 1 in 100 chance of failing, which could inundate a local valley with toxic sludge that could flow into Washington rivers, according to two reports from Conservation Northwest and the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Indian Reservation.

The toxic mining waste from Copper Mountain Mine is held in place by two unstable earthen dams, said Mitch Friedman, executive director of Conservation Northwest. Regulations require the likelihood of dam failure to be less than 1 in 1 million, he said.

However, because the annual probability of the dams failure is so high, Friedman said, any seismic activity or bad weather could liquify the base of the dams.

“If you could win the lotto with 1 in 100, you’d buy every ticket every time,” he said, of the likelihood of the dams failing.

Not odds he’d take with a catastrophe that could be prevented, Friedman said.

Copper Mountain Mine officials did not respond to interview requests.

The sludge is a byproduct of mining for copper. The mining operation blasts rocks, which dump trucks take to an area to be crushed. That crushed rock is run through a chemical process to remove the copper.

The moderately toxic leftovers are run through a machine that separates out the wet and dry byproducts. The wet products are sprayed inside a pond. The coarser material is deposited to create the tailings dams, which raises the dams around 15 feet each year, according to a report by Steve Emerman, a consultant who specializes in the environmental impacts of dams.

The two tailings dams are at the east and west ends of the facility. The east dam is around 540 feet tall, and the west dam is around 566 feet tall, according to the reports. The pond stores 309 million metric tons of mine tailings, Emerman said. Each dam is expected to reach its permitted height by 2027, Emerman said.

“At the permitted elevation, the east and west dams will be unstable,” Emerman said.

If regulators approve the mine’s proposed expansion plans, the west dam would become the second largest tailings dams in the world, more than 250 feet taller than the Seattle’s Space Needle, according to the reports.

Tailings dams are known to have an annual probability of failure that’s at least 10 times greater than hydropower dams, Emerman said. He estimated the annual probability of the Copper Mountain Mine tailings dams failing could range from 1 in 1,000 to 1 in 100.

“The annual probability that I found was actually not that surprising for a tailings dam,” Ermerman said. “The disturbing part is to have such a typically high annual probability of failure side by side with such extreme consequences.”

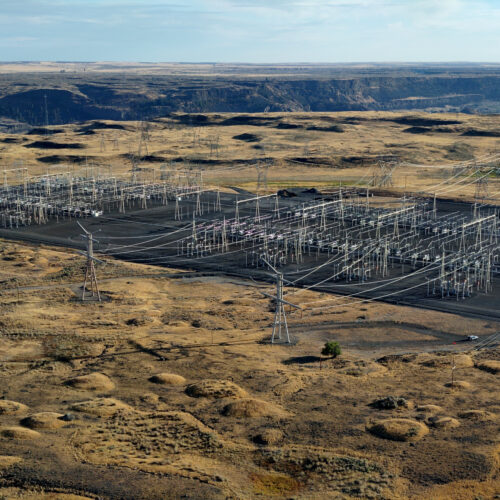

The tailings pond at Copper Mountain in British Columbia. CREDIT: Edgar Bullon/ Courtesy Of Conservation Northwest

According to the reports, the western dam would cause the most harm to downstream communities if it failed. The town of Princeton, B.C., around nine miles downstream, is the biggest concern.

Lynker Technologies developed the breachment assessment report of the Copper Mountain tailings dams. The report simulated 62 different ways the dams could fail. At a mid-range failure, which would release around 40% of the sludge, parts of Princeton would be covered in 30 feet of the waste within 90 minutes, according to the report.

“That depth and subsequent impact force of the mudflow would have significant destructive potential,” said Josh Sturtevant, a water resources scientist with Lynker Technologies.

To help prevent deaths in the event of such a catastrophe, Friedman recommended installing an alarm system for Princeton, so people could get to higher ground as quickly as possible.

In the mid-range scenario, the sludge along the Similkameen River Valley would range from zero to 65 feet, according to the report. The valley’s steep topography would constrict the debris flow, creating considerable depths of the sludge, according to the report.

The Similkameen River, where Copper Mountain Mine is located, flows into the Okanogan River, which is a tributary of the Columbia River. According to the simulation, as the sludge settles out over the following 20 days, it eventually could reach water near Pateros, Washington.

“It’ll be right on our doorstep and would flow into Washington, impacting our people and our resources and our Columbia River salmon,” Friedman said.

Some of the first places that could get inundated would be ceded lands of the Colville Tribes, said Colville Chairman Jarred-Michael Erickson.

“The tribe has spent a lot of time and money and work to restore (Endangered Species Act) listed species,” Erickson said.

The Colville Tribe has worked to restore chinook and sockeye salmon in the Similkameen and Okanogan river, he said.

“This year is one of the bigger salmon returns in recent years,” Erickson said, estimating a return of 600,000 fish.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, a record number of sockeye salmon are returning to the upper Columbia and Okanogan rivers this year, the most since counting began at Bonneville Dam in 1938.

In addition, the tribe also has restored lamprey in the Okanogan and Similkameen rivers, Erickson said.

Moreover, Erickson said, a cleanup would be incredibly costly and time-consuming, including habitat work and water quality issues.

“In my lifetime, we probably wouldn’t see it restored to what it was or what it should be,” Erickson said, of potential cleanup work if the Copper Mountain Mine tailings dams failed.

“I feel like it would be insurmountable, the amount of time and money it would take,” Erickson said, of a cleanup.

It’s not all hyperbole, Friedman said.

A tailings dam failed in 2014 in central British Columbia at Mount Polley Mine, what the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation called the worst mining disaster in Canada’s history. According to a CBC report, hundreds of tons of arsenic, lead, copper, and nickel flowed into Polley and Quesnel lakes and Hazeltine Creek when the dam’s foundation failed because of flaws in its design.

After the Mount Polley failure, a review panel recommended a list of regulations to prevent this type of disaster. Those regulations included using the best available technologies at existing tailings dams and improving guidelines to protect public safety.

However, critics said many regulations haven’t been fulfilled.

“British Columbia needs to do a much better job of preventing these scenarios. I think the regulators, engineers, government, and the mining industry maybe have a little bit of arrogance or hubris,” Friedman said.

Preventing disaster is a lot less costly than cleaning up one, Erickson said, especially a disaster that he said would likely not be cleaned up in his lifetime.

The tribe would like all mining operations to cease immediately, Erickson said.

“With these dams, anything could happen at any time, so time is of the essence,” Erickson said.

Friedman said the mining sludge could be placed into more permanent storage, such as existing open pits from mining operations.

Mining is important for the renewable energy future, he said, but it must be done responsibly and with thought for communities downstream.

“We need these minerals. We cannot have a clean energy revolution unless we have copper. And we shouldn’t sacrifice our rivers for our atmosphere and our climate. That means better mining. It means dry storage. It means better regulations,” Friedman said.