How Blue Mountain Heart To Heart Treats Drug Addiction In Eastern Washington

Listen

(Runtime 3:33)

Read

Like much of the nation, Benton and Franklin Counties are experiencing a dramatic increase in the number of people dying from overdoses and drug related issues. So as Franklin and Benton Counties work toward opening a joint behavioral health and drug treatment center in Kennewick.

There is one organization already doing the work locally.

When Blue Mountain Heart to Heart first opened in the mid-80’s, the agency was dedicated to helping people suffering from HIV-AIDS in the Tri-Cities.

Everett Maroon is Executive Director of this community health agency.

“Initially it was to help them die with dignity before there were any therapeutics on the market and then later as case managers to help them navigate medical and other systems as HIV turned into a chronic condition.”

Since then, the focus at Blue Mountain Heart to Heart has grown to serve other marginalized groups including people battling substance abuse.

The agency offers “low barrier” treatments for opioid addiction. Those include prescribing methadone to help users wean off the drug and needle exchanges

Maroon knows these treatments have detractors, but has seen them help people struggling with addiction.

“We have so stigmatized people who use drugs that we stigmatize the you know the treatments for those patients…going back to we didn’t really have mental health care right that’s where we sort of the 12 step stuff started in the early 20th century. And, and I will say it works for some people in total abstinence works for some people, devoid of any medication.”

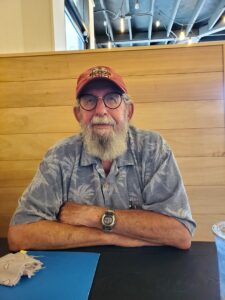

Chuck Eaton was one of the first to start a needle exchange program in the 60s in New York.

These methods are actually long-standing practices for treating people addicted to drugs. Chuck Eaton has spent his career working in harm reduction and opioid recovery. He was one of the first to set up mobile needle exchanges back in the early 60’s in New York.

Eaton “the sooner you could be helpful to a person, the easier and more successful it was to attempt to find alternatives. So early intervention was a good thing. And then there was treatment or recovery.”

By providing clean needles, bleach, and opioid recovery where people lived, Eaton and his colleagues found success in treating addiction.

Eaton: “It’s history is that recovery has been possible for some people using a 12 step approach…The other side of that issue is that not only is it possible to restore somebody’s control of their own life choices through the years of a drug like methadone.”

When Franklin and Benton Counties open their planned Three Rivers Behavioral Health Recovery Center in Kennewick, it won’t offer these same services. Instead, it will be a place for inpatient detox and mental health care.

Although Blue Mountain Heart to Heart’s Everett Maroon was not consulted in the planning for that facility, he is seen as an authority on the topic.

He co-wrote the opioid intervention plan for Greater Columbia Behavioral Health or GCBH. That’s the agency responsible for the delivery of medically necessary behavioral health crisis services in the region without income requirements. It covers nine counties in Washington and the Yakama Nation.

Blue Mountain Heart to Heart is one of 9 agencies that works with Greater Columbia Behavioral Health. The committee that runs the GCBH are elected county commissioners from each county that is served. Maroon believes the state needs to increase funding across the state. And step up with more expert advice and money to help those in Eastern Washington.

Chuck Eaton agrees. He would like to see medical experts serving on the boards of public health and not just elected officials. A bill was passed in the state in 2021 to add medical experts onto local health boards and not just county elected officials.